Story highlights

Lebanon has maintained relative stability despite the civil war raging next door

Last week's assassination of a top intel official may have changed that

Syria still plays a major role in Lebanon, despite pulling out its troops in 2005

Not too long ago, there were just as many news reports about Beirut’s fancy nightclubs and the Lebanese capital’s embrace of modern living as there were stories about violence.

Lebanon had maintained relative stability despite the full-tilt civil war that has torn apart its largest neighbor and former military occupier, Syria, for more than a year and a half.

The war has triggered some sectarian conflicts inside Lebanon, and that raised concerns – but no alarm bells – about a broader conflict.

Now, that may have changed.

The trigger came Friday, when a car bomb exploded in central Beirut, killing Lebanon’s top intelligence official, Brig. Gen Wissam al-Hassan. He publicly opposed Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. Many in Lebanon immediately suspected al-Assad’s regime in the assassination.

Pockets of sporadic fighting have erupted across the country. Lebanon’s army made an unprecedented move by issuing a statement demanding that politicians order their supporters to calm down.

“The country’s fate is at risk,” the statement said. “Tension in some areas is increasing to unprecedented levels.”

Lawmakers who are most opposed to Syria’s influence inside Lebanon – mostly through its Lebanese ally, Hezbollah – are now calling for the government’s resignation.

Lebanon is a country on the brink. And many observers believe that the longer Syria’s conflict goes on, the more destabilizing it will be for Lebanon.

Here’s an overview of where things stand and how they got to this point:

Why was Lebanon’s intelligence chief assassinated last week? What does that have to do with Syria?

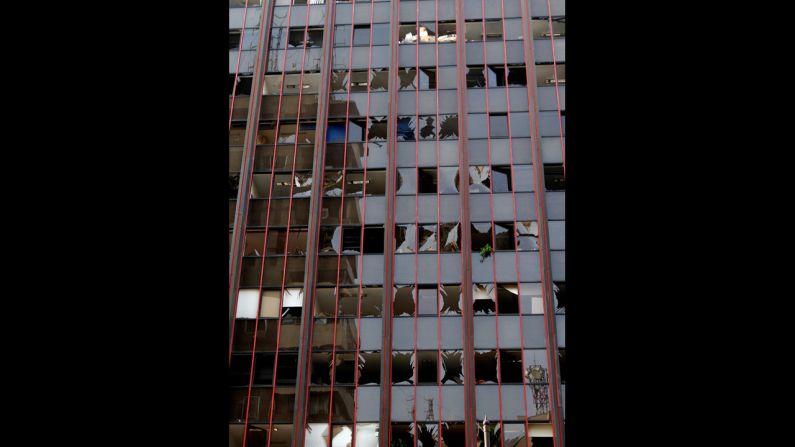

On Friday, the man who once led investigations into the targeted killings of high-profile Lebanese officials was killed himself in a massive car bomb in Ashrafiyeh, the typically peaceful and cosmopolitan district of East Beirut that he called home.

Lebanese officials said there was no doubt al-Hassan was the target of the attack.

Al-Hassan: A polarizing figure

Speculation immediately fell to Syria, even though Damascus and its ally, Hezbollah, both condemned the attack. Lebanon vowed to hunt down the perpetrators, and the United States dispatched FBI agents to help in the investigation.

Al-Hassan may have been targeted because he was leading an investigation into a Lebanese politician, Michel Samaha, who is accused of working with two Syrian officials to plan attacks inside Lebanon.

How much control does Syria have inside Lebanon?

Syria ended its military occupation of Lebanon in 2005, bowing to international pressure after the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri. Yet the country maintains influence through Hezbollah, a powerful Shiite political party that has links with the al-Assad government and currently dominates Lebanon’s government.

Hezbollah is also an Iran-backed paramilitary group deemed a terrorist organization by the United States, whose agents inside Lebanon were indicted by the United Nations for Hariri’s assassination.

Elements of Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Mikati’s allianceare firm, if quiet, supporters of the al-Assad regime. But the government is more interested in keeping Lebanon from getting dragged into the conflict, says Middle East expert Chris Phillips of Queen Mary, University of London.

“They’re aware they’re a weak government, and they’re not keen on Lebanon becoming a staging point for the rebels to launch attacks on Syria,” Phillips said. “But there hasn’t been a major drive to push the Free Syrian Army out of the country because the government knows a large segment of the Lebanese population supports the rebels.”

Why do Lebanese support Hezbollah, which is considered a terrorist group by the U.S.?

Hezbollah, experts say, is popular inside Lebanon because it has managed to do what the Lebanese government at large has failed to pull off: efficiently provide cradle-to-grave services.

To the West, Hezbollah is an enemy. The United States has long designated it a terrorist organization, blaming it for a series of kidnappings and for setting off truck bombs in 1983 that killed more than 200 U.S. Marines in Beirut. Hezbollah was also behind the hijacking of a TWA flight in 1985, which produced infamous footage of a pilot leaning out of the cockpit with a gun to his head.

Hezbollah was created in 1982 to oppose Israel’s occupation of Lebanon. Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, it waged violence against its chief target, Israel, sparking violence between those nations and, by proxy, fanning the tension among their allies.

But inside Lebanon, it runs hospitals and schools, provides college counseling and employs traffic cops. The group reinforces its message on its own al-Manar satellite television channel and broadcast station.

That has not stopped it from amassing substantial political power inside Lebanon, according to author and journalist Thanassis Cambanis.

“They provide in a fair and efficient way, but Hezbollah is also authoritarian, power-hungry and militaristic,” said Cambanis, who has reported extensively in the region for the Boston Globe and the New York Times. “They believe in a religious and pious society that embraces a fundamentalist Shia Islam. They believe in self sufficiency through war.”

Iran and Syria support Hezbollah’s ideology. Both countries have provided the group, which has a military wing, with financial backing and weapons for years. Hezbollah also makes millions through illegal businesses around the world, including global drug trafficking, the U.S. has charged.

Have there been widespread protests in Lebanon? Against what?

Protests have been more isolated. After al-Hassan’s funeral Sunday, angry protesters clashed with security forces and rushed toward Mikati’s office in central Beirut, calling for his dismissal. The mob hurled sticks, stones and flags. A smaller, peaceful demonstration continued later Sunday as government figures called for calm.

Most of the protesters are allied with Sunni coalitions that have long been sharply critical of the Lebanese government’s perceived closeness with the Syrian regime, blaming Mitaki for not preventing Friday’s deadly car bomb.

Why could Syria’s problems become Lebanon’s? They’re two different countries, after all.

The major concern for Lebanon is that Syria’s troubles will reopen the wounds of Lebanon’s 15-year-long civil war, which ended in 1990.

Lebanon has always struggled to maintain a balance among its religious and ethnic sects, and the current tensions mirror those in Syria: In both countries, the Shiite and Alawite Muslim sects (al-Assad is an Alawite) tend to support the Syrian regime, while support is growing among Sunni Muslims for Syrian rebels.

The country also has a large Christian population, and both Sunni and Shiite groups have lobbied for Christian support during past conflicts.

Sunnis are in the majority in northern Lebanon, where they have clashed with a small but strong enclave of pro-al-Assad Alawites. The core of the Syrian president’s support in Lebanon is in the southern part of the country.

The good news is that the war exhaustion factor is very high in Lebanon, Phillips explained. Beirut is still recovering from Israel’s shelling of the city in 2006 during a 34-day conflict sparked by Hezbollah’s kidnapping of Israeli troops near the Lebanese border, and many other wounds from the 1975-90 civil war have yet to heal.

“There’s been an assumption for several years that the Lebanese people are fed up and exhausted with civil war,” Phillips said. “The civil war there ended not because of any resolution but simply because people lost the will to keep fighting.”

CNN’s Nick Paton Walsh, Ashley Fantz and Nick Thompson contributed to this report.