Story highlights

In the last few weeks of the race, both campaigns will be battling over a tiny sliver of undecided voters

Polls show somewhere between 3% to 8% of voters haven't yet made up their minds

The campaigns are still spending millions of dollars chasing down this slice of the electorate

Matt Ankenbruck has made it virtually impossible for the presidential campaigns to get to him.

He hasn’t seen much of the $30 million worth of TV advertising spent in the swing state of Colorado by President Barack Obama and GOP challenger Mitt Romney. He threw out his television after the O.J. Simpson verdict in 1995.

They won’t get him in print, either. He canceled his subscription to his hometown paper because “So much of what we get in the media is negative. … I don’t wanna fill my mind with this negative stuff.”

Phone calls from the campaigns? Nope. He says he’s too busy working to pick up the phone. Same with Internet ads and social media. Hasn’t seen them, though he says he might soon use Wikipedia to learn a bit more about Romney.

Ankenbruck is a white Roman Catholic independent who voted for Obama in the 2008 election and lives in a hotly-contested suburb outside of Denver. He is both an anomaly – most voters live much more “on the grid,” own TVs and follow news on the Internet – and exactly the type of voter both campaigns are pouring millions of dollars into wooing.

He and other undecided voters represent a narrow sliver in swing states. Many, political experts say, are either politically clueless or have waffled for months on their choice for the Oval Office.

They’re unemployed white males trying to climb out of the recession. They’re single mothers who have been too busy to focus on the campaigns until now. They’re young families who may have voted for Obama in 2008 but are now somewhat disillusioned or confused. They’re frustrated Republicans who have not yet been able to warm up to Romney, despite a nine-month primary season.

CNN Electoral Map: You do the math

For instance, underneath Romney’s controversial “47%” comments unearthed last week was an acknowledgment that there are only a tiny number voters who are still persuadable. And, implied in the ongoing debate around voter laws in several states is an accusation that those laws may discourage slivers of voters from turning out on Election Day.

That’s why these voters are highly coveted by both Romney and Obama. Both campaigns realize they have to secure their base of supporters while, at the same time, pursue and win over that dwindling, fickle slice of persuadable voters who have yet to make up their minds.

It is a pricey strategy, targeting a shrinking group.

Poll: Obama up by five points in Ohio

Depending on the poll, the percentage of U.S. voters who say they are undecided ranges from 3% to 8%. In the battleground state of Ohio, a recent poll showed that about nine in 10 voters have made up their minds.

Compare that to 1988 when George H.W. Bush was running against Michael Dukakis. Roughly 20% of voters in that race said they were undecided or wobbling several months out but that number tightened to 14% after Labor Day, according to a New York Times poll at the time. Bush eventually won by eight points.

“If you think about what these ads are trying to do, they are trying to convince that 7% in the 20% of states that matter,” said John Geer, chairman of Vanderbilt University’s political science department. “It’s a small slice instead. These people might be undecided but they tend not to follow politics and might not turn out to the polls.”

The fight for a narrow slice of voters has become increasingly tough in recent years, Geer said.

Years ago, there was “very little nationalization of American politics,” he said. Stump speeches were specific to the local audience, rarely made national news, and rarely influenced undecided voters.

Today, a speech delivered in St. Augustine, Florida, could easily be viewed by someone living in Ft. Collins, Colorado.

That is if they watch TV.

From rhetoric to reality

When Ankenbruck voted for Obama in 2008, he said it was because “I liked his rhetoric. I thought he was sincere. Fresh. New. I thought he was going to bring the country forward.”

Featured in “The Hope and the Change,” a film by conservative advocacy group Citizens United, Ankenbruck added that four years later, he feels disillusioned by what he sees as Obama’s inability to end the partisan bickering in Washington and help pass legislation that is palatable to both parties. He’s especially put off by a federal mandate requiring religious institutions to offer their employees insurance coverage for contraception.

So recently, Ankenbruck has been thinking he might vote for Romney. But he’s not sure.

“I am leaning toward him just on principle that he’s a Republican,” Ankenbruck said, adding “At this point I haven’t got a lot of specifics.”It isn’t for lack of trying.

This year, in his home state of Colorado, the campaigns and their well-heeled Super PACs spent nearly $30 million trying to reach voters like Ankenbruck, according to an analysis of figures provided by Campaign Media Analysis Group (CMAG). In the Denver media market, which includes the key Jefferson County where Ankenbruck lives, Obama’s campaign has spent $6 million and the Romney campaign $3.4 million to reach voters.

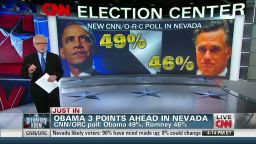

In the 2008 elections, Obama netted 53.6% of the vote in that county compared to John McCain’s 44.6%. According to a NBC News/WSJ/Marist Poll released Thursday, 4% of Colorado voters are undecided with 50% supporting Obama and 45% supporting Romney.

A lot of money chasing fewer voters

Analysts say it is precisely the huge amount of money spent by the campaigns that has reduced the pool of undecided voters. If the campaigns “weren’t spending all this money the distribution of votes would be different,” said Lynn Vavreck, a political science professor at the University of California Los Angeles who has polled thousands of voters over the past year.

“Whatever that share of undecided voters is it’s not the same … every day,” Vavreck said. “They move in and out of that category every day. … Half of the people who are undecided in December have come to a vote choice and may have changed their minds since then. There is a good bit of fluidity to that chunk of people.”

Ankenbruck is still feeling pretty fluid when it comes to his vote. He figures he might pay closer attention during the debates.

Failing that, he knows that campaign volunteers will soon come knocking.

“Yeah,” he sighs and then laughs. “I guess I better get ready for that.”