Story highlights

NEW: "After this week, something's going to have to change," parent says

Striking teachers reconvene Tuesday after weighing proposed deal

A judge will consider city's request to end the strike Wednesday

There have been no classes in Chicago since September 7

Chicago public schoolchildren will spend a seventh day out of classes Tuesday as their striking teachers weigh a tentative proposal to end their walkout.

School officials went to court Monday to ask a judge to declare the strike illegal and order the teachers back to work. A Cook County judge will hold a hearing on that request Wednesday.

In the meantime, Chicago Teachers Union delegates are scheduled to convene again Tuesday afternoon to discuss a proposed settlement. And parents and city officials scrambled to keep about 350,000 children busy and out of trouble as the strike stretched into its second week.

“It is frustrating for me that the kids are not in school, and I have to find other ways to continue their education,” said parent Will White, who said he’s sympathetic to both sides in the dispute. “Hopefully, it won’t last too much longer … after this week, something’s going to have to change.”

Chicago Public Schools, the third-largest U.S. school system, and the union struck a tentative bargain Friday afternoon. But Sunday, union members decided to continue the walkout while its they reviewed the proposal.

“We have 26,000 teachers, and they’re all able to to read this document and take some time to discuss its merits or its deficiencies, and that’s going to happen today,” union spokesman Jackson Potter told CNN. “We’re just asking people to be patient and let the process run its course.”

Q&A: What’s behind the Chicago teachers’ strike?

But Mayor Rahm Emanuel vowed Sunday night to force the teachers back into the classroom, calling the teachers’ move “a delay of choice that is wrong for our children.” The school system went to court Monday morning, arguing that the walkout violates Illinois labor laws.

“State law expressly prohibits the CTU from striking over non-economic issues, such as layoff and recall policies, teacher evaluations, class sizes and the length of the school day and year,” the district said in a statement. “The CTU’s repeated statements and recent advertising campaign have made clear that these are exactly the subjects over which the CTU is striking.”

The strike also prevents “critical educational and social services, including meals for students who otherwise may not receive proper nutrition, a safe environment during school hours and critical services for students who have special needs,” the district continued.

Cook County Circuit Judge Peter Flynn has scheduled a hearing on the district’s request for 10:30 a.m. Wednesday. The system isn’t asking the judge to settle the dispute that led to the walkout, just to order the teachers back to work.

The union responded to the filing Monday by saying it “appears to be a vindictive act instigated by the mayor.”

“This attempt to thwart our democratic process is consistent with Mayor Emanuel’s bullying behavior toward public school educators,” the union said.

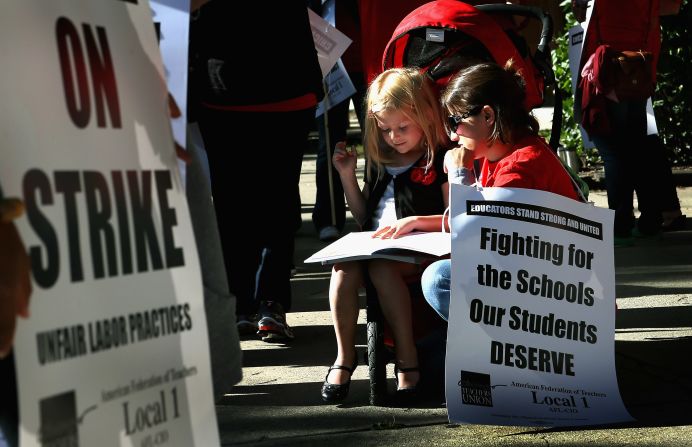

Teachers walked off the job September 10, objecting to a longer school day, evaluations tied to student performance and job losses from school closings. Parents have juggled their families’ schedules for more than a week to make sure their children are attended to while schools are closed.

“Besides the daycare issue, they just need to be in school,” said Rich Lenkov, a parent who took part in a protest outside the school district’s headquarters on Monday. “Their competitors in charter schools and private schools are learning, while our kids are not.”

Interview with a parent on the impact of the strike

With the strike continuing, the school system planned to open 147 “Children First” sites citywide Monday for students to go to, in addition to programs run by the city’s park department and neighborhood organizations, Chicago Board of Education President David Vitale said.

Vitale said that he, like the mayor, is “extremely disappointed” that such programs are necessary. “There is no reason why our kids cannot be in school while the union reviews the agreement,” he said.

But Nancy Davis Winfield, the mother of another student, said she stood behind the teachers and the union.

“I think its going to be settled this week, but I understand what the teachers are doing and they’ve got to read that fine print,” Winfield said as she picked up her daughter at a Children First program in the South Loop district.

“I feel that the whole nation needs to understand that this is a fight for the middle class,” Winfield said. “Democrats are talking about supporting the middle class. This is the fight that has to be waged.”

Union members reconvene Tuesday afternoon following a break on Monday for the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah. They could decide to end the strike at that point, which could mean classes coming back Wednesday. But the rank and file would still have the opportunity to accept or reject the proposed contract, and CTU President Karen Lewis said a “clear majority” of their delegates did not want to suspend the strike.

“They are not happy with the agreement,” she said.

Negotiations have taken place behind closed doors while the public debate has been marked by sometimes biting remarks and vocal picketing around the schools.

Lewis said one problem is that “there’s no trust” of school board members, with job security the chief issue.

“The big elephant in the room is the closing of 200 schools,” she said. The teacher “are concerned about this city’s decision on some level to close schools.”

It was not immediately clear where Lewis got the 200 figure or when she believes such school closures might happen. But Chicago Public Schools spokeswoman Marielle Sainvilus called Lewis’ claim “false,” asserting that union leaders said a few days ago that 100 schools would close, and “I’m sure it’ll be another number tomorrow.”

“All Ms. Lewis is trying to do is distract away from the fact that she and her leadership are using our kids as pawns in this process,” Sainvilus wrote in an e-mail.

Another point of contention involves the teacher evaluation system, Lewis said. The tentative contract would change it for the first time since 1967, taking into account “student growth (for the) first time,” according to the school system. And teachers who are rated as “unsatisfactory and developing” could potentially be laid off.

Principals would keep “full authority” to hire teachers, and the school system will now have hiring standards for those with credentials beyond a teacher certification. In addition, “highly rated teachers” who lost their jobs when their schools were closed can “follow their students to the consolidated school,” according to a summary of the proposed contract from Chicago Public Schools.

This contract calls for longer school days for elementary and high school-age students, 10 more “instructional days” each school year and a single calendar for the entire school system, as opposed to the two schedules now in place, depending on the school.

The pay structure would change with a 3% pay hike for the first year of the contract, 2% for the second year and 2% for the third year. If a trigger extends the contract to four years, teachers will get a 3% pay increase. Union members would no longer be compensated for unused personal days, health insurance contribution rates would be frozen, and the “enhanced pension program” would be eliminated.

As is, the median base salary for teachers in the Chicago public schools in 2011 was $67,974, according to the system’s annual financial report.

For high school athletes, strike could put scholarships on the line

CNN’s Kyung Lah reported from Chicago and Greg Botelho from Atlanta. CNN’s Ted Rowlands, Chris Welch, Katherine Wojtecki and Ed Payne also contributed to this report.