Editor’s Note:

Story highlights

Beirut's vibrant, cosmopolitan nightlife is renowned throughout the region

After 15 years of civil war, Beirutis have a "seize the day" attitude, say locals

It also reflects the liberal, tolerant outlook often found in this diverse port city

In 1984, in the midst of Lebanon’s civil war, Naji Gebran started hosting regular gatherings at his Beirut beachfront apartment for the purpose of “musical therapy.”

Weary and traumatized from the conflict that had divided their city – and would claim some 150,000 lives over its 15 years – people would come to his apartment to lose themselves in a night of jazz, blues, funk, soul, classical and Arabic music.

“They used to come because of the music, to forget the war,” said Gebran. “We used to do this for peace.”

The party nights were an important outlet, he said, as during the war years there were few other options.

“My friends had nowhere to go,” he said. There were two or three clubs in Christian east Beirut, the same in the city’s Muslim west.

“But they were very constipated. Very good dress, the same music all the time,” he said. “It was very commercial, easy listening, everywhere you go.”

Beirut has come a long way since then.

After dark, the city comes alive: A balmy playground of chic nightclubs, rough and ready dives, stylish rooftop bars.

The hip, hedonistic scenes in the fashionable neighborhoods of Gemmayze or Hamra are unlike anything to be found elsewhere in the Arab world – and can be an unexpected find in a country in which austere Islamic militant group Hezbollah forms part of the government.

“It is the nightlife capital of the region,” said Naomi Sargeant, managing director of city guide Time Out Beirut. “It’s cosmopolitan and has this East-meets-West feel. I don’t think there’s anything on par.”

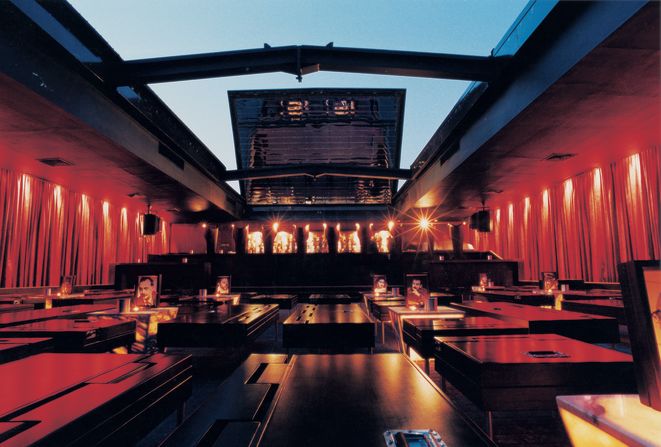

A fixture of the Beirut scene is Gebran’s nightclub, B018. Opened in 1994, and named for the lock-code on the door of his old apartment, the club has helped to usher in a more cosmopolitan, vibrant nightlife in the aftermath of the war, he said.

“When I opened the club, artists start to go out, lesbians and gays started to go out,” he said.

Beirut’s vibrancy is partly an expression of a Lebanese lust for life, a determination to seize the day after having endured years of war and associated traumas, said Sargeant.

“With all the issues you’ve had here, people just want to enjoy life. It tends to be: let’s just live it up today. We can worry about the rest tomorrow.”

But it also reflects a cosmopolitan tradition that has long been part of the character of this diverse Mediterranean port city, a thriving trading center for thousands of years and a place where 18 officially recognized religious sects live – most of the time – in a state of respectful coexistence.

This cultural capital is one of his country’s greatest national assets, said Gebran.

“The people are more liberal, more free, they love life. We say this is our petrol, it’s our oil.”

While liquor vendors in some other parts of Lebanon have been targeted with protests and even violence in recent times, Beirut has a liberal, tolerant attitude towards drinking.

“The tolerance for drinking is very similar to Europe, so you don’t have the same issues you do in other countries in the region,” said Sargeant.

Beirut’s nightlife was centered in areas where local communities had no issues with alcohol, she said: “I have seen no evidence of any clashes with any religious groups about the nightlife in Beirut. Everyone coexists.”

One distinctive aspect of the city’s nightlife was that it was not unusual to see a wide age range of people out enjoying themselves – even multiple generations of a family.

“In the late ’60s and early ‘70s, Beirut was considered the place to come and party, but when the war happened that got all cut off. A whole generation couldn’t go out and enjoy themselves,” said Sargeant.

“So when the war ended a generation wanted to see their kids go out and enjoy themselves, and the parents themselves want to recapture what they lost from their youth.

“I’ve seen tables where it’s all the parents at one and all the kids on another table.”

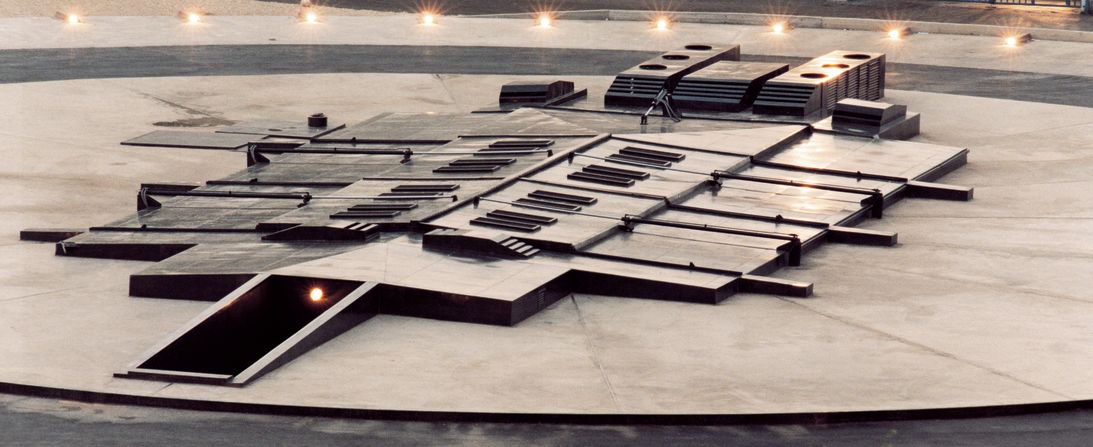

At B018, the connections and disjunctions between Beirut’s war-torn past and hedonistic present are referenced in the very architecture. It looks like a bomb shelter.

Situated near Beirut’s port in a district known as Karantina, the site was once a slum home to thousands of Kurdish and Palestinian refugees. On January 18, 1976, a massacre by local militias killed hundreds and left the area abandoned.

The club was designed by Gebran’s cousin, the architect Bernard Khoury. Its striking underground design is, in Khoury’s words, “a reaction to difficult and explosive conditions that are inherent to the history of its location – and the contradictions that are implied by the implementation of an entertainment program on such a site.”

A subterranean club might not seem to make much sense in a city where rooftop bars are the most popular option, but the club’s roof opens to make the most of balmy evenings – or mornings, for the truly dedicated.

It is at that point, said Sargeant, the genuine bon vivants are likely to continue partying, heading to beach clubs to the city’s north and south for a swim and another drink on a sun lounger.

Beirutis are known for making good use of the attractive natural surroundings beyond the city limits; in July and August 2006, the city’s social set decamped to the mountains to avoid the hostilities with Israel. This time, war didn’t stop them.

“A lot of people packed up and went up to the mountains,” said Sargeant. “People were loading their shopping trolleys with cigarettes and whiskey … The party moved up there.”

CNN’s Eye On series often carries sponsorship originating from the countries we profile. However CNN retains full editorial control over all of its reports. Read the policy