Story highlights

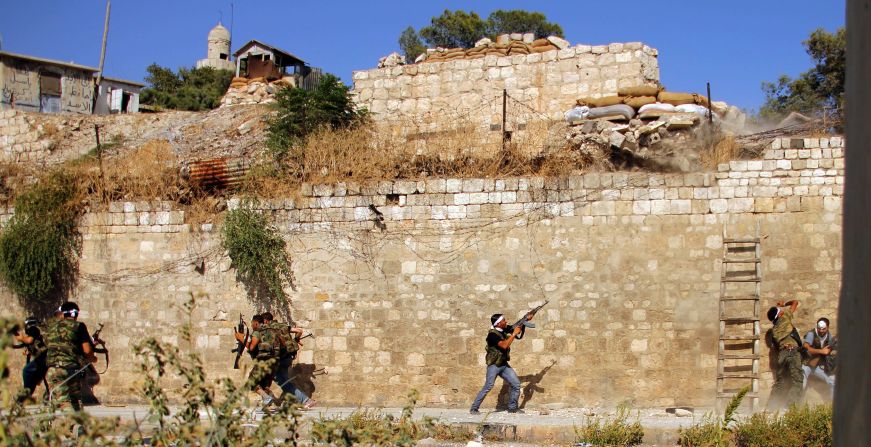

The Red Cross has determined that Syria is in a state of civil war

This means international humanitarian law applies wherever there is fighting

The Geneva Conventions, overseen by the Red Cross, govern behavior in war zones

They lay the legal groundwork for war crimes prosecutions

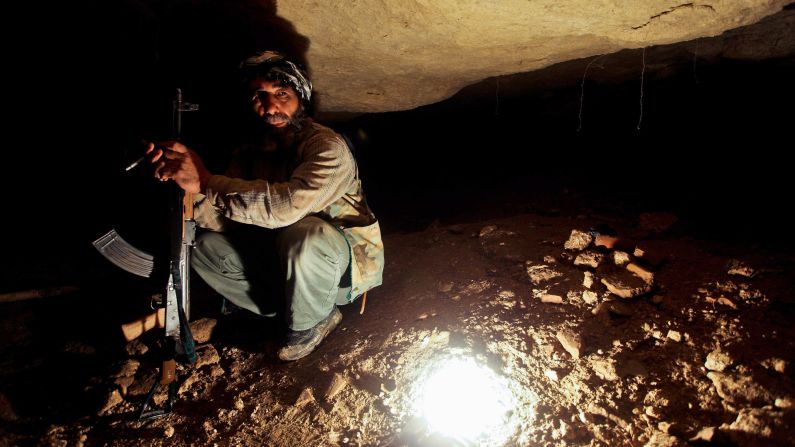

The Red Cross’s declaration Sunday that Syria is engaged in a civil war – or in the organization’s legalistic phrasing, a “non-international armed conflict” – may have struck some observers as a case of stating the obvious.

But the assessment from the Geneva-based body is significant. It means the violence that has plagued the Middle Eastern nation since early 2011 has crossed a legal threshold whereby combatants throughout the country are subject to the Geneva Conventions – and as such can be prosecuted for war crimes.

Who are the Red Cross?

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is the guardian of the Geneva Conventions, which set down the rules of war.

The organization was formed after the Battle of Solferino in 1859 in Italy. A Swiss businessman, Henry Dunant, encountered nearly 40,000 wounded, dying and dead lying unattended on the battlefield. He subsequently lobbied for the establishment of a permanent humanitarian relief agency to act during times of war, protected by a government treaty recognizing the neutrality of the agency and safeguarding its operations.

These goals were realized through the establishment of the Red Cross and the First Geneva Convention, ratified by 12 nations in 1864. Dunant was jointly awarded the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901 for his efforts.

Part of the Red Cross’s legal mandate is to determine whether an armed conflict exists, and whether international humanitarian law applies.

What is the ICRC’s new assessment of the situation?

The ICRC’s classification of the violence as a “non-international armed conflict” means international humanitarian law will extend beyond the three regions in Syria where the organization had previously determined to be areas of armed conflict – namely Homs, Hama and Idlib – to apply wherever fighting occurs.

“These rules impose limits on all parties on how fighting can be conducted, with the aim of protecting the civilian population and persons not, or no longer, directly participating in the hostilities,” said ICRC spokeswoman Carla Haddad Mardini told CNN.

The ICRC will work to remind both the Syrian government and the armed opposition of their obligations to respect international humanitarian law, and share its analysis of what is occurring with both sides.

It is hoped this will have an effect on the way the war is fought, by helping to regulate the conduct of fighters and safeguard the rights of innocents affected by the violence.

How was the violence in Syria classified previously?

For months, the Red Cross has classified the violence in Syria as internal armed conflicts between government forces and armed opposition groups localized to three flashpoints mentioned above.

But the spread of hostilities to other areas has led the Swiss-based agency to conclude the fighting meets its threshold for an internal armed conflict. International humanitarian law now applies “wherever hostilities take place,” the organization said Monday.

What are the Geneva Conventions?

The Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols are international treaties that, in the words of the Red Cross, “contain the most important rules limiting the barbarity of war.”

Applicable during times of armed conflict, they form the cornerstone of international humanitarian law, setting rules for the treatment of people who are not participating in the fighting – civilians, health workers and aid workers – as well as for the wounded, sick or prisoners of war.

Read the 1949 Geneva Conventions here

Common Article 3 of the conventions, which relates to “non-international armed conflicts” – the most common form of conflict in the world today – is applicable to the situation in Syria. “The term “civil war”, often used as a synonym for “internal armed conflict” (or) “armed conflict not of an international character,” has no legal status,” said Mardini. Special rules apply to the most serious contraventions of the law, which are termed grave breaches and constitute war crimes.

What counts as a “grave breach?”

These crimes include willful killing, torture or inhumane treatment, including biological experiments; willfully causing great suffering or serious injury; and wanton, unlawful extensive destruction and appropriation of property not justified by military necessity.

Read the definition of grave breaches here

Nations that are party to the conventions have an obligation to seek and put on trial or extradite those responsible for grave breaches, regardless of their nationality.

What is the history of the Geneva Conventions?

Efforts to moderate the behavior of soldiers are as old as recorded history itself. In the sixth century BC, the Chinese general and military strategist Sun Tzu suggested specific restrictions on military conduct, while in 1625, the Dutch theorist Hugo Grotius called for civilian protections in “On the Law of War and Peace.”

Throughout the history of warfare, agreements on the rules of war were defined by custom or negotiated between generals prior to battle, but did not extend widely beyond the conflict in question.

The modern Geneva Conventions were adopted in 1949, in the aftermath of World War II, and expanded their focus to include civilians for the first time, in an attempt to prevent another outbreak of the “total war” which had wreaked havoc on civilian populations.

Who recognizes the Geneva Conventions?

The Geneva Conventions entered into force on 21 October 1950 and have gradually grown in recognition to become universally applicable. More than 70 countries ratified the conventions during the 1950s, and today 194 nations are party to the agreement.

Do they have an impact on the battlefield?

According to the ICRC, yes. While the nature of war has changed radically in the decades since the conventions were drafted, they continue to act as a powerful deterrent to the commission of atrocities in times of conflict. The ICRC’s director of international law Philip Spoerri told CNN in 2009 that enforcing compliance with the conventions, rather than recodifying their core principles, should be a priority for international humanitarian law.

Simon Hooper contributed to this report.