Story highlights

It's nearly impossible to estimate how many U.S. citizens are dual nationals, experts say

Dual citizenship not recognized in U.S., but residents are not forced to choose

Not all countries allow dual citizenships with the U.S., among them Japan and India

Dual citizenship can create issues involving taxes, military service, same-sex marriages

Irena Sharoshkina Boostani came to the United States in 1998 with $450 and few plans.

After growing up in a small town in Russia, she met a Peace Corps volunteer from California who told her she should consider moving to America. As soon as she could, Boostani headed for Los Angeles.

Boostani, now a 35-year-old mother of two, has dual citizenship in Russia and the United States after marrying an American citizen.

“The duality is really an opportunity to bring the two homes together,” said Boostani, who lives in San Diego. “My existing home is definitely America – there is no question in my mind. My mom and dad are still in Russia, and having that dual citizenship is peace of mind I can go back and forth. It feels free, it really does.”

It is nearly impossible to estimate how many U.S. citizens have dual – or even triple – citizenships, says Michael A. Olivas, an immigration professor at the University of Houston Law Center.

It’s like estimating “how many people in the United States have blue eyes,” he says, because there is no single registry of these individuals, and the numbers change so rapidly.

The number is likely well over 1 million, he says, and is probably several times that.

For those millions, the road to holding two passports is not always simple.

The United States does not formally or officially recognize dual citizenship, says Daniel Cosgrove, a spokesman for the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

During the naturalization ceremony, individuals officially become U.S. citizens when they take the Oath of Allegiance to the United States. The text of the naturalization oath became regulation in 1929 and states, “I hereby declare, on oath, that I absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state or sovereignty, of whom or which I have heretofore been a subject or citizen.”

In practice, the naturalization oath means if naturalized citizens were ever faced with a choice of allegiance to the United States or a different nation, they have an obligation to choose the United States, says Michael Wildes, a partner in the New York-based immigration firm Wildes & Weinberg, which has represented high-profile clients including John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

The understanding, Wildes says, is a U.S. citizen will “work in concert with the U.S. Constitution but never against it.”

Pledging allegiance

There are large contingents of U.S. citizens who are also citizens of Canada, Mexico and the United Kingdom, Olivas says, though dual citizens represent a host of other countries.

Charles Foster, a former senior policy adviser to George W. Bush and a managing partner at FosterQuan, one of the largest immigration law firms in the United States, says he tells clients dual citizenship can be viewed as “two for the price of one.”

“You don’t have to make an agonizing decision to give up citizenship. You can have both,” he says.

According to the U.S. State Department website, federal law “does not mention dual nationality or require a person to choose one citizenship or another.”

It is possible to become a dual citizen in the United States in several ways, says Catherine Wilson, an associate professor of political science at Villanova University who specializes in immigration politics.

These include being born in the United States to at least one immigrant parent whose home country grants the child automatic citizenship, or being born in certain countries to at least one parent who is a U.S. citizen.

If not a citizen by birth, people can go through the naturalization process in the United States and remain dual citizens if they are not required to renounce citizenship in their countries of origin.

Issues of dual citizenship become complicated because they are unique to each country and depend on the relationship each has with the United States.

Although many countries allow dual citizenship with the United States, several require renunciation of citizenship in the country of origin if an individual becomes naturalized as a U.S. citizen – a process known as forced expatriation. Those countries, according to the Migration Policy Institute, include Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, Kenya, Botswana, Afghanistan, Indonesia, Japan, the Philippines, Thailand and India, among others.

In general, it is harder to gain dual citizenship with a country the United States “does not have a favorable relationship with, or is at war with,” Wilson says.

Since the founding of the United States, leaders have been concerned about Americans’ political loyalty, Wilson says.

There was “the concern that even people who would be our leaders would have these foreign allegiances that would lead them astray and have them sympathize on behalf of foreign powers,” she says.

From the time of the Constitutional Convention, the U.S. government has debated the costs and benefits of foreign allegiances.

“That debate still is with us in so many ways,” Wilson says.

Serving abroad, and other pitfalls

Complications with dual citizenship can come into play for many reasons, including when people have an obligation to join another country’s military because of a religious or spiritual commitment.

Ben Pester, a 20-year-old living in New Jersey, was born in Israel to American parents and has dual citizenship in those countries. He and his family moved to the United States when Pester was 13.

As an Israeli citizen, Pester would have been required to serve in the Israeli army. But because he lives outside the country, he was able to defer the obligation by agreeing to limit the length of any stays in Israel.

Pester says his Israeli ties have been significant to his parents because of their Jewish faith.

“Israel is a very holy place for them, and they have a sense of pride knowing their son is Israeli,” Pester says.

Wildes suggests dual nationals tell the State Department if they plan to serve in another country’s military.

Unlike joining the Israeli army, joining the military of a country in conflict with the United States is grounds for automatic expatriation, Olivas says.

But short of taking up arms against the United States or being convicted of treason, dual nationals may participate in a variety of activities abroad, including voting, without having their U.S. citizenship revoked, according to Wildes and Olivas.

Other pitfalls dual nationals face include filing tax returns, Wildes says, especially when working with an accountant or tax preparer who is unfamiliar with the tax laws of both countries.

In some cases, people can be taxed by both home nations by mistake. In other cases, they might be penalized if they mistakenly fail to pay taxes in one country.

Additional challenges have come into play with increasing recognition of same-sex marriages. Although recognized in several states, when it comes to immigration law such marriages are not recognized by the U.S. government. As a result, there are occasions in which same-sex spouses are “forced off U.S. soil,” Wildes says.

For example, a same-sex marriage involving only one U.S. citizen is not grounds alone to allow the non-U.S. spouse to live here legally, he says.

Moving toward seamlessness

Overall, ease of travel and living abroad has improved for dual citizens over time, Wildes says.

Countries are moving toward “seamlessness” of travel to make entering and exiting their borders easier, he says, especially since a main reason many individuals have dual citizenships is for “ease of commerce.”

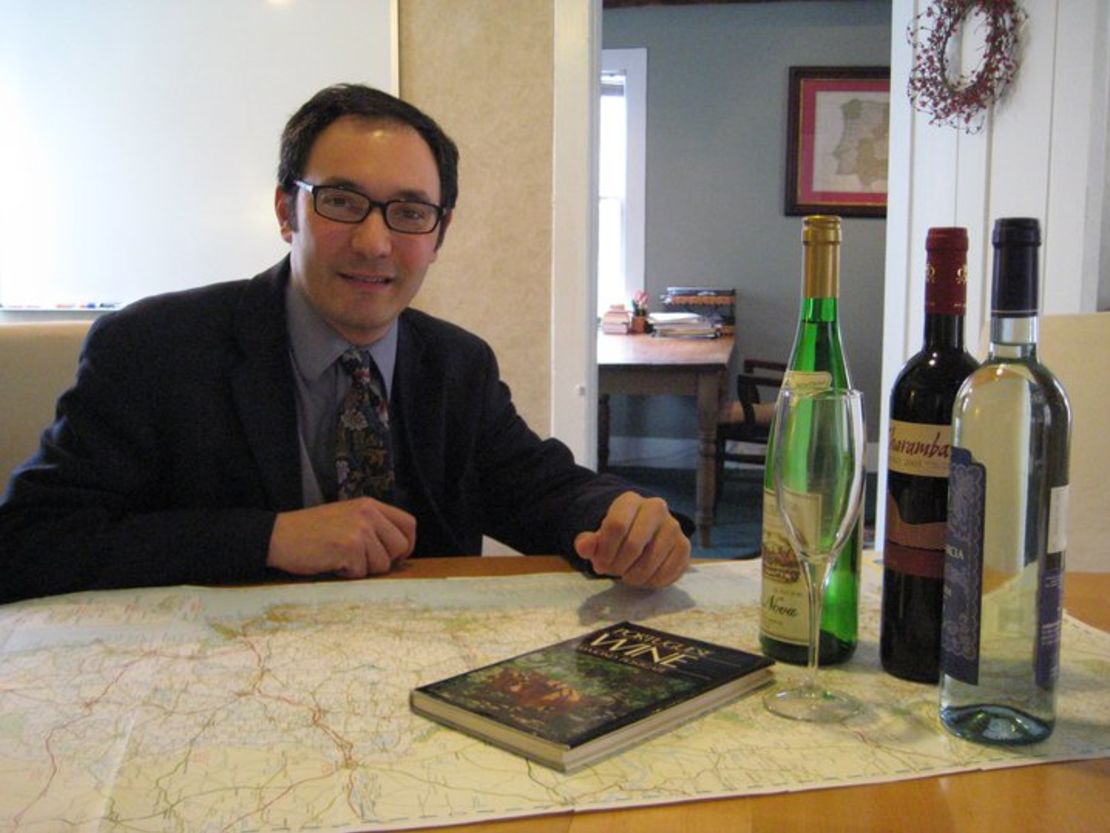

Though he was born in Chicago and now lives in New Hampshire, Jayme Simões, 44, is going through the process of obtaining Portuguese citizenship.

Simões’ father was Portuguese, making citizenship in that country possible. Simões speaks Portuguese fluently and frequently conducts business in Portugal, so getting a second passport makes sense, he says.

“I’m proud to be an American,” he says, “but I love Portugal.”

Similarly, 35-year-old Andres Arango – a dual U.S.-Colombian national – enjoys the benefits of having two passports.

“Having a passport from Colombia is a burden. You have to have a visa to go anywhere in the world,” he says. “You cannot have an impromptu trip to Europe because you need a visa. It takes time and it takes money. For that reason, the (U.S.) passport is amazing. The ability to travel freely around the world with a blue passport is great.”

In addition to easier travel, people might have other reasons for pursuing dual nationality, including potential tax benefits.

Every four years, immigration policies get another look-over for one competitive reason: Olympic athletes sometimes pursue dual citizenship to put them in better standing to compete, Olivas says.

Nationality and identity

Many people pursue dual citizenship because it is important to their identities.

Diane Saarinen, a 48-year-old living in Brooklyn, recently became a Finnish citizen in homage to her deceased parents.

She was born in New York, and her parents were Finns who never became U.S. citizens.

Saarinen grew up speaking Finnish and spending childhood summers playing with lambs and cows in the Scandinavian countryside, and she began to miss that part of her identity without her parents to keep it alive.

To stay connected, she became involved in the Finnish community in New York, which eventually led to her desire for Finnish citizenship.

She has no set plans to return to Finland but says moving to Spain or Finland one day sounds like “an exotic retirement plan.”

Plus, her dual citizenship is meaningful for her 89-year-old aunt, who was 16 when she moved to the United States from Finland.

Katarina Bridova, a 34-year-old native of Slovakia now living in Connecticut, became a U.S. citizen in February because of her desire to actively participate in this year’s presidential election.

“I chose to become a U.S. citizen because I want to vote,” she says. “I pay taxes and I’ve been part of the discussion. … I don’t really follow Slovak politics. I’m present here, and I want to take advantage of it.”

Dual nationality has become an issue of self-reflection, says Villanova’s Wilson, a question of “who are we as a country?”

Understanding the debate can be difficult because the rules can seem “fuzzy and ambiguous,” she says, and there is no “central repository” for information about dual citizenship.

Boostani, the Russian who moved to Los Angeles, says she wishes the nuances of being a dual citizen were easier to understand.

“When it comes to people who are already here and are trying to establish themselves, whether immigration-wise or socially or economically, there is not enough information about that,” Boostani says. “Or if there is, it’s very dispersed and you can’t find all the information in one place.”

For now, Boostani says she is working to bring her family members to the United States from Russia, and has already been successful in helping her younger brother make the journey.

“I’m building up my family here because this is where my base and home is,” Boostani says. “Being able to travel freely … that’s amazing. That’s a privilege.”