Editor’s Note: Peter M. Shane is the Jacob E. Davis and Jacob E. Davis II Chair in Law at the Ohio State University’s Moritz College of Law.

Story highlights

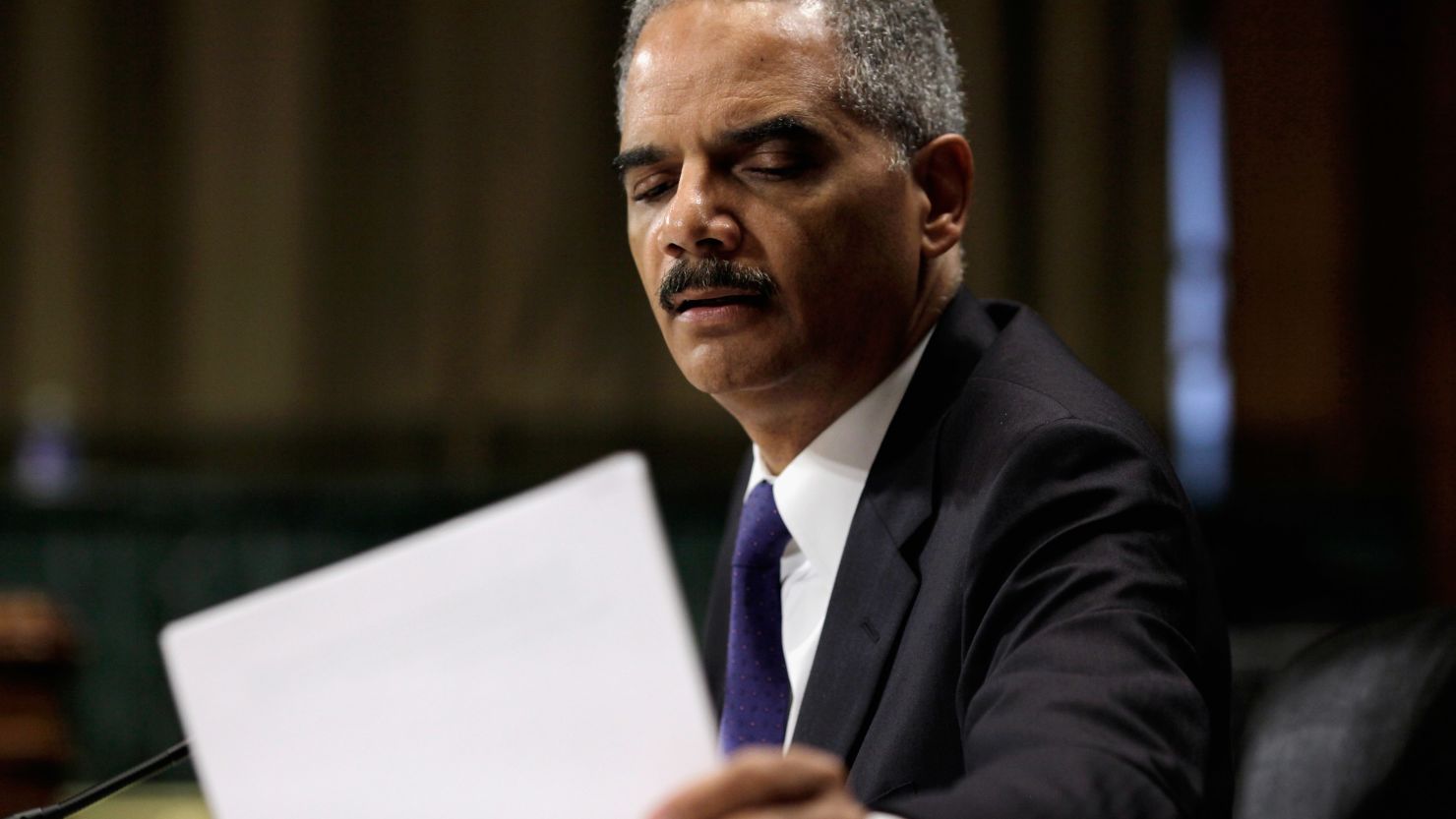

In party-line vote, House panel recommends holding U.S. attorney general in contempt

Panel's action follows assertion by the president of executive privilege on some documents

Peter Shane: Disputes over privilege are common; White House seems to have edge

Public will likely see this as a partisan dispute rather than a matter of justice, Shane says

For veteran Congress watchers, President Barack Obama’s formal claim of executive privilege regarding certain Justice Department documents related to Operation Fast and Furious will generate a sense of déjà vu.

Disputes over legislative access to executive documents occur in almost every presidential administration. Their resolution inevitably entails a set of legal and political considerations that change from episode to episode.

Unfortunately for the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, its legal position is uncertain at best, and almost all political considerations would seem to favor the White House.

Whether or not the full House votes Attorney General Eric Holder in contempt, the likeliest resolution will be an informal settlement in which the Justice Department expands slightly on its current offer of disclosure, the committee narrows the range of documents it is demanding, or both compromise in a mutual, face-saving gesture. At least, that would be likely in politically “normal” times.

The form of executive privilege at stake in the current dispute is “deliberative privilege.”

Deliberative privilege aims to protect documents generated anywhere in the executive branch that embody only the executive’s internal deliberations, not final policy decisions.

Deliberative privilege is not a legal absolute. The executive branch concedes that when another branch of government demands privileged documents within the executive’s control, they sometimes have to be turned over.

They have to be turned over when the demanding branch can articulate a compelling need for the information to fulfill one of its own constitutional functions – a need that outweighs the executive branch’s interest in confidentiality.

A key problem now for the House Oversight Committee is thus far it has yet to state in a very concrete way why it needs the particular documents it is demanding.

In contrast, the executive branch has articulated a strong and highly specific reason for withholding the documents at issue: Forced disclosure to Congress of internal deliberations concerning how best to interact with Congress would undermine the executive’s capacity to function as a co-equal branch. It would undermine the prospects for future candid deliberations about interactions with the other institutions of government.

Resolving such a dispute sounds like a matter for the courts, but the judiciary is unlikely to be of much practical help now to the House.

If the House brings a civil action to enforce its subpoena, the matter is unlikely to resolved by the courts before the election or, indeed, before the expiration of the current Congress.

The House could ask the U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia to prosecute Holder for contempt, but the Justice Department long ago took the position – in a very careful opinion written by then Assistant Attorney General Theodore Olson – that the department is not required by law to prosecute executive officials for contempt when the ground for subpoena noncompliance is a claim of executive privilege.

So that would leave the House with the one remaining legal option of launching an impeachment investigation, which brings us to the political side of things.

The reality Congress faces in separation of powers disputes, no matter how genuine or how principled, is that the public will almost certainly not rally around Congress if it perceives the dispute as more political food fight than anything else.

With no Democrats supporting the committee vote – and I am guessing few, if any Democrats supporting a contempt citation by the entire House – that’s just what this will look like.

Moreover, as with Whitewater, it will be hard for House Republicans to explain exactly what the problem is. Fast and Furious appears to have been a disaster, but the Justice Department has shared documents freely on Fast and Furious.

The Justice Department sent a letter to Congress in February 2011 that mistakenly denied reports about what the Bureau of Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives actually did in Fast and Furious. But the department has been forthcoming in sharing information about the events leading up to that letter, which Holder subsequently withdrew.

The fight, then, is not about a botched ATF operation or about a botched letter to Congress.

It is about how the attorney general reached his eventual conclusion that Fast and Furious was “fundamentally flawed” and decided how to respond to congressional and other requests for information about a program he now concedes should not have happened. Politically, this now begins to sound like Whitewater – a story hardly anyone can follow, which really does not seem to implicate fundamental issues of public policy or official integrity.

(One caveat: The dynamics of this dispute could change if it turns out that Republican Committee Chairman Darrell Issa actually has information that the process of responding to Congress after the February 2011 letter entailed specific instances of corruption. Were he to bring such specific information to the attention of the White House, it would be consistent with past White House practice to release all documents related to that misconduct.)

A prolonged fight over Fast and Furious led by Republicans will do two things their presumptive presidential nominee, Mitt Romney, surely does not want. It will fill up air space that could otherwise have been spent discussing the economy, and it will intensify the appearance of congressional Republicans as the obstructionists blocking the changes Obama so famously promised.

It also must be said that Issa’s past attacks on the administration amply feed a narrative that his subpoena is about politics, not principle.

Having months ago called Obama “one of the most corrupt presidents in modern times” – in the face of such modern historical escapades as Watergate, Iran-Contra or the Terrorist Surveillance Program – the chairman is not well-situated to play a Sam Ervin-like role, policing the presidency more in sadness than in angry partisanship.

In short, unless the House has specific information not yet disclosed suggesting the information it seeks is closely linked to the exposure of government malfeasance we have not yet heard about, this fight will end in a standoff or the parties will finally compromise.

To put the matter in yet fuller context, here are some questions and answers about the dispute and the history of executive privilege:

What is executive privilege?

Executive privilege is really an umbrella concept that encompasses a variety of privileges. History’s most famous claim of executive privilege – President Richard Nixon’s unsuccessful attempt to withhold the “Watergate tapes” – was an example of “presidential privacy” privilege. That privilege covers executive communications when the president is involved.

The executive branch, however, historically claims a much broader privilege, the so-called “deliberative privilege.”

Deliberative privilege aims to protect documents generated anywhere in the executive branch that embody only the executive’s internal deliberations, not final policy decisions. The current dispute involves “deliberative privilege.”

Where does executive privilege come from?

The Supreme Court has held that the authority of the executive branch to withhold certain documents from mandatory disclosure is rooted in the separation of powers. The court stated, in United States v. Nixon (1974), that the importance of confidentiality to protect “communications between high government officials and those who advise and assist them in the performance of their manifold duties … is too plain to require further discussion.”

It concluded that “the privilege can be said to derive from the supremacy of each branch within its own assigned area of constitutional duties.”

In that sense, executive privilege is a form of power that the Constitution never mentions, but which the Supreme Court has found implicit in our constitutional structure. In that respect, it is just like Congress’ investigative power, which is also not mentioned in the Constitution.

Why is the president involved in claiming privilege over Justice Department documents?

Withholding documents from Congress is always a sensitive matter, legally and politically. For this reason, presidents have long reserved to themselves the final decision of when and whether to invoke any kind of executive privilege against Congress.

President Ronald Reagan formalized this process in a November 1982, memorandum. It states: “Historically, good faith negotiations between Congress and the executive branch have minimized the need for invoking executive privilege, and this tradition of accommodation should continue as the primary means of resolving conflicts between the branches. To ensure that every reasonable accommodation is made to the needs of Congress, executive privilege shall not be invoked without specific presidential authorization.”

Why is the White House claiming executive privilege regarding Operation Fast and Furious?

Operation Fast and Furious appears to have been a gravely misbegotten attempt by the ATF to nab drug traffickers in Mexico by allowing lower-level gun traffickers to buy weapons in the United States for the Mexican cartels and then tracing the guns’ movement, rather than stopping their export. One of the guns may have been involved in the December 2010 killing of U.S. Border Patrol Agent Brian Terry.

On February 4, 2011, Assistant Attorney General Ronald Weich wrote a letter to Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa, the ranking minority member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, which mischaracterized the operation. He incorrectly denied that ATF “knowingly allowed the sale of assault weapons to a straw purchaser who then transported them into Mexico.”

As a result, the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, chaired by Issa, has been investigating not only the original operation but also the circumstances that led to the erroneous February 4, 2011, letter.

For his part, Holder directed the Justice Department’s inspector general to investigate Fast and Furious and publicly denounced the operation in October 2011 as “fundamentally flawed.” The Justice Department has released to Congress more than 7,600 pages of documents revealing how Fast and Furious was initiated and carried out.

What the Issa committee is now demanding, and what the White House and Justice Department are withholding, are documents generated after February 4, 2011, relating to how the Justice Department handled its responses to Congress regarding Congress’ oversight of Fast and Furious, following the erroneous Weich letter.

In his June 19 letter to the president seeking the invocation of executive privilege, Holder argued that to disclose these documents would ” ‘significantly impair’ the Executive Branch’s ability to respond independently and effectively to matters under congressional review.”

More specifically, “Congressional oversight of the process by which the executive branch responds to congressional oversight inquiries would create a detrimental dynamic” that would, in turn, “chill the candor … of executive branch discussions and ‘introduce a significantly unfair imbalance to the oversight process.’ “

Is the executive privilege claim valid?

United States v. Nixon held that, with the possible exception of documents pertaining to military and state secrets, executive privilege is not absolute but “qualified.”

Under a “qualified privilege,” documents that are potentially exempt from mandatory disclosure might still have to be released to another branch of government. This would happen when the institutional needs of the demanding branch to acquire the information in support of its own constitutional functions are weightier than the harms that would follow should the executive branch be forced to disclose it.

Congress typically takes the position that this balancing process always favors Congress, a proposition with which the executive disagrees and for which there is no judicial precedent.

As matters stand, the executive branch has articulated a strong and highly specific reason for withholding the documents at issue: They would shed no light on any policy issue before Congress and would directly intrude on the executive branch’s capacity to figure out how to respond to legislative inquiries, consistent with the executive’s own independent constitutional role.

To Congress, the Justice Department is saying, in effect: You can ask us questions, you can judge our answers, but you cannot eavesdrop on the process by which we formulate our answers. For its part, Issa’s committee has not made clear in any concrete terms why it needs the documents it is demanding.

It has not, for example, made a prima facie case of criminal wrongdoing in the Justice Department’s post-February 11, 2011, actions, on which the documents now demanded would shed some light. As long as the dispute remains in this posture, the Justice Department’s claim falls well within the executive branch’s longstanding interpretation of its prerogatives under the separation of powers.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Peter Shane.