Story highlights

Emily Herx says she was fired because she received in vitro fertilization treatments

She was a teacher at a Catholic school in Indiana

The diocese says core issue raised in suit challenges its right to use religious standards

A teacher at a Catholic school in Indiana is suing the diocese where she worked after being fired because the in vitro fertilization treatments she received were considered against church teachings.

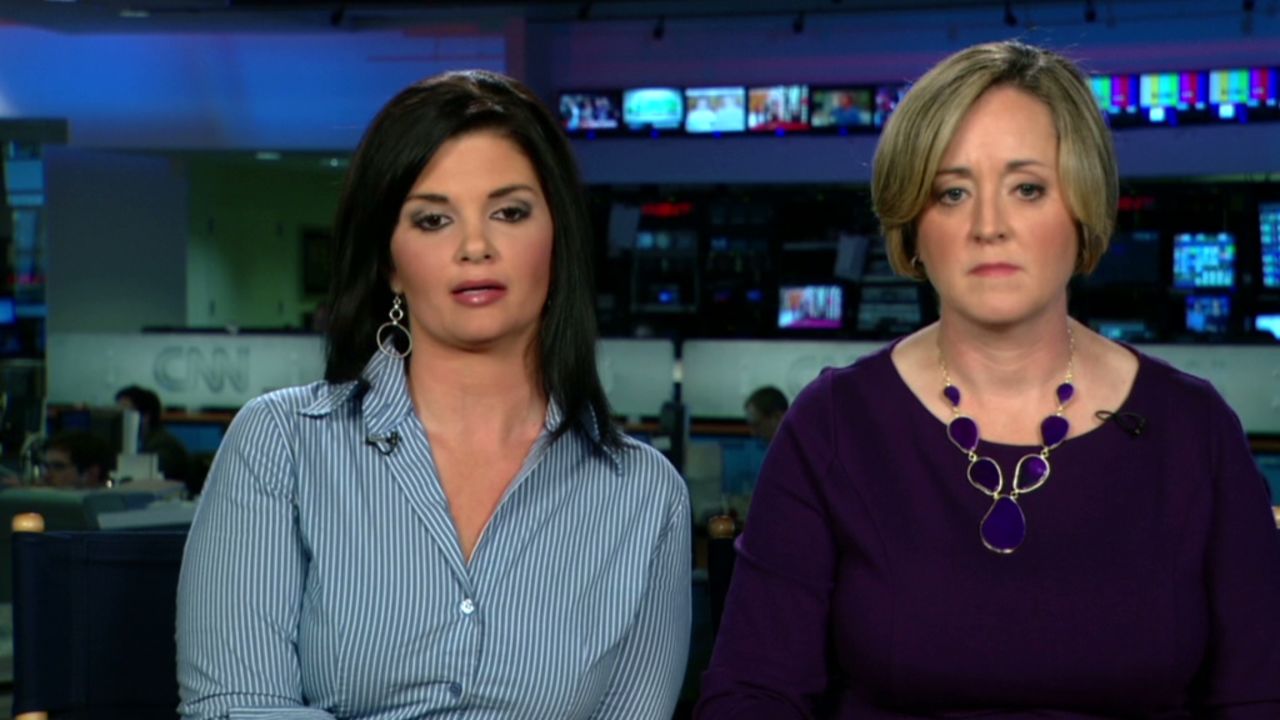

Emily Herx, a former English teacher at St. Vincent de Paul School in Fort Wayne, filed a federal lawsuit against the school and the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend.

She says in the suit filed Friday that she was discriminated against in 2011 after the school’s pastor found out that she had begun treatments with a fertility doctor, according to the complaint.

Herx says the school’s priest called her a “grave, immoral sinner” and told her she should have kept mum about her fertility treatments because some things are “better left between the individual and God,” the complaint said.

“I didn’t think I was doing anything wrong,” Herx told CNN on Thursday. “I had never had any complaints about me as a teacher.”

The diocese responded, saying it “views the core issue raised in this lawsuit as a challenge to the diocese’s right, as a religious employer, to make religious based decisions consistent with its religious standards on an impartial basis.”

In its statement, diocese officials said that “the church promotes treatment of infertility through means that respect the right to life, the unity of marriage, and procreation brought about as the fruit of the conjugal act. There are other infertility treatments, such as in vitro fertilization, which are not morally licit according to Catholic teaching.”

The statement adds that teachers working in the diocese are required to “have a knowledge and respect for the Catholic faith, and abide by the tenets of the Catholic Church.”

Herx said she underwent her first in vitro fertilization treatment in March 2010, and immediately told her supervisor, the school’s principal.

“The first time she was made aware that my husband and I had to go through fertility treatments, she said, ‘You are in my prayers,’ ” Herx said. “To me, that was support.”

It was after she requested time off for her second treatment more than a year later that the school’s pastor, Msgr. John Kuzmich, requested to meet with Herx, according to the complaint.

During the meeting, Herx says Kuzmich told her that it would have been better if she hadn’t said anything about the treatments because they could cause a scandal.

Eleven days later, Herx said, she was notified that her contract at the school would not be renewed because of “improprieties related to church teachings or law.”

Observers say Herx’s case bears some of the hallmarks of the case of Cheryl Perich, a former teacher who was fired from a religious school in Michigan after taking a medical leave of absence in 2004.

At issue was whether the Americans with Disabilities Act applies to hiring and firing decisions involving “ministerial employees,” such as teachers who teach secular subjects. The U.S. Supreme Court decided that Perich – who taught secular subjects along with a religion class – was considered a “minister” and could in fact be fired based on church doctrine.

“The interest of society in the enforcement of employment discrimination statutes is undoubtedly important,” Chief Justice John Roberts said at the time. “But so too is the interest of religious groups in choosing who will preach their beliefs, teach their faith and carry out their mission.”

Herx and her lawyer, Kathleen DeLaney, say that since Herx taught only English, she should be exempt from the so-called ministerial exception.

Herx noted that after being hired at St. Vincent de Paul School in 2003, she never taught religion and never held an official title within the Catholic Church.

But some legal observers say that because Herx worked at a Catholic school, her decision to undergo fertility treatments could be construed as a clash with the school’s broader mission.

“The doctrine exists in order to protect the religious institution’s right to protect their message,” said Richard Garnett, a law professor at the University of Notre Dame.

But Gregory Lipper, senior litigation counsel at Americans United for Separation of Church and State, disagreed, saying that deeming an English teacher “a minister” in a religious school constitutes “Exhibit A of what goes wrong if the exception becomes too broad.”

“If a teacher of purely secular subjects is considered a minister, then the implication of that is that everyone who works for a Catholic school would be considered a minister,” he said. “It becomes an open license to discriminate.”

CNN’s Bill Mears contributed to this report.