Editor’s Note: Phil Clark is a lecturer in comparative and international politics at SOAS, University of London, and co-founder of Oxford Transitional Justice Research.

Story highlights

Taylor trial highlights three main shortcomings of international courts, says Phil Clark

Length of the Taylor trial is unjustifiable, delaying justice for his victims, he says

Clark: Taylor trial suffered from the narrowness of the charges against him

Clark: Taylor trial weakened by distance of trial from location and victims of his crimes

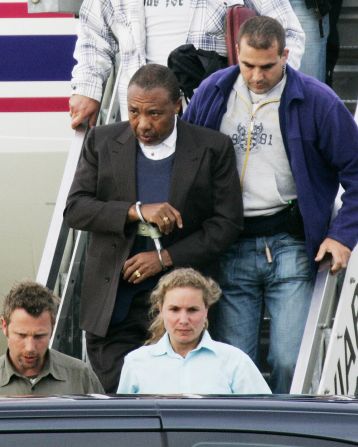

The long overdue verdict in the case of the former Liberian President Charles Taylor will be widely celebrated as a critical achievement for international criminal law. Taylor has been on trial at the special court for Sierra Leone since 2006 on 11 charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including murder, rape, pillage and the conscription of child soldiers.

Charles Taylor: Lay preacher and feared warlord

Champions of international justice will highlight the unquestionable importance of prosecuting a former head of state, which signals that political seniority is no guarantee of immunity. They will also see the child soldier charge against Taylor as particularly pertinent, given the recent focus on this crime in Africa by the Kony 2012 internet campaign and the International Criminal Court’s (ICC) conviction of Congolese warlord Thomas Lubanga.

But amid the celebrations at the end of the Taylor trial, important questions should be asked about the future of international justice. In the next few years, the war crimes tribunals for Sierra Leone, Rwanda, the former Yugoslavia, Lebanon and Cambodia will all close their doors, leaving the ICC as the sole international judicial institution. The Taylor trial asks two main questions that impinge on the ICC’s ongoing work: does international justice genuinely help victims of mass crimes and are lengthy, expensive international trials a worthwhile investment by foreign donors in the age of austerity?

For victims in Sierra Leone, Taylor’s verdict brings relief

One answer to these questions is that it is of greater benefit to victims and better value for donors to invest in rebuilding domestic judicial institutions in conflict-affected countries rather than whisking atrocity suspects off to The Hague.

See high-res photos of the Charles Taylor years

The Taylor trial highlights three main shortcomings of all international criminal justice institutions.

First, the length of the Taylor trial is unjustifiable, delaying justice for his victims, dulling the societal impact of the case and increasing the financial costs. That it has taken the special court six years to deliver a verdict is partly due to the legal complexity of the case but also to the histrionics of international defense and prosecution lawyers, who have constantly sought media and donor attention.

Key grandstanding moments during this trial included Taylor and his defense counsel twice walking out when judges demanded their participation and the prosecution’s distraction of calling Naomi Campbell as a star witness. The case has also been delayed because several of the international legal personnel have other professional commitments alongside their work for the court. These included Taylor’s defense counsel and one of the judges, who halfway through the trial took up a new role at the International Court of Justice.

Second, the Taylor trial suffered – as all international criminal cases do – from the narrowness of the charges against him. Because of the inherent length and expense of international trials, prosecutors typically focus on crimes that they can most easily prove, rather than those that may be most representative of the suspect’s atrocities or most salient in the eyes of affected populations. While the 11 charges against Taylor are more expansive than those brought against most international suspects, they still ignore arguably Taylor’s most egregious crimes, namely those committed in his home country, Liberia, because of the special court’s mandate which focuses solely on crimes committed within Sierra Leone.

The trial also overlooks the role played by Taylor’s various foreign backers, which during the conflict in Sierra Leone included Libya, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire and a host of international corporations that profited from the blood diamonds used by Taylor-backed rebels to fund their military campaign. Without the training, logistical and financial support of these outside actors, Taylor could never have wrought such destruction on Sierra Leonean soil.

Finally, the Taylor trial was weakened by the distance of the trial from the location – and the victims – of his crimes. In 2006 because of security concerns, the Freetown-based Special Court for Sierra Leone transferred Taylor to The Hague to be prosecuted in a courtroom leased from the ICC. This denied victims the opportunity to see firsthand the justice being done in their name. The distance also limited the number of Sierra Leoneans who could be called as defence and prosecution witnesses, which decreased the quality of evidence weighed by the Court.

The problem of distance for international institutions is more than geographical and also one of a particular international legal mentality. Even international courts such as those for Sierra Leone and Cambodia, which are based in-country, are often wilfully detached from those societies, citing the need to remain neutral and impartial from domestic political influences. The transplant of foreign modes of law, with its wigs and gowns, and imposing, high-security courtrooms separate international law from local populations, even when those courtrooms are physically located in conflict-affected countries. Further highlighting this separation, when these international institutions pack up and leave in the coming years, they will have contributed little to the building of domestic legal infrastructure or training of local judicial personnel, who will have to carry on the task of delivering justice long after foreign lawyers have departed.

These problems in the Taylor case highlight the inherent limitations of international criminal justice. Meanwhile, the recent example of high-level Rwandan genocide suspects being extradited home to face justice in a heavily reformed domestic system – and in front of the Rwandan population – highlights other important possibilities. In particular, it suggests that a new donor focus on supporting domestic judiciaries around the world might not only make financial sense but also deliver more tangible benefits to victims and societies recovering from mass conflict.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Phil Clark.