Story highlights

Coral beds 7 miles from the well suffered heavy damage, researchers say

"It tells us it's likely this oil hit a lot of other areas of the seafloor," one scientist says

The findings of the late-2010 expedition are being published this week

Nearly 5 million barrels of crude are believed to have poured into the Gulf in the 2010 spill

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill damaged coral formations deep beneath the surface of the Gulf of Mexico and miles from the ruptured well at the heart of the disaster, researchers reported Monday.

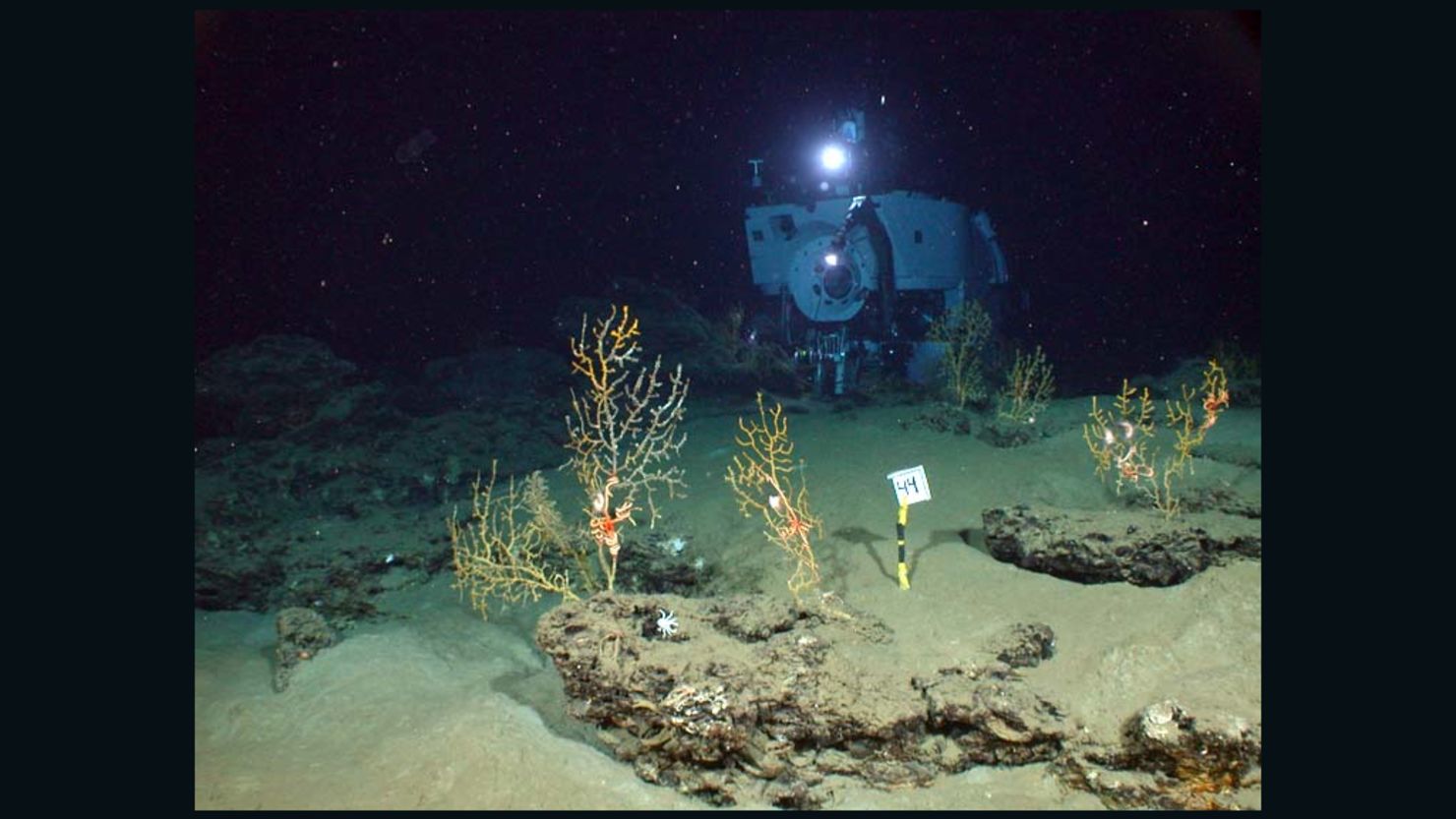

Scientists using remote-controlled probes and the venerable research submersible Alvin spotted a coral colony covered in “black scum” about 7 miles (11 kilometers) southwest of the undersea gusher, Penn State University biologist Charles Fisher said. Another nearby formation was covered in a gooey brown and white mix of oil and organic materials from the coral, he said.

“What this does tell us is there was acute damage to a reef 7 miles away,” Fisher said. “It tells us it’s likely this oil hit a lot of other areas of the seafloor.”

Fisher was the chief scientist for an expedition that surveyed the area in November and December 2010 with funding from the National Science Foundation. Some of the findings are being published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Samples taken from the coral beds, located at a depth of about 4,300 feet, matched the chemical fingerprint of the oil from the Macondo well, said Helen White, the lead author of the paper documenting the results.

An estimated 4.9 million barrels (206 million gallons) of crude poured into the Gulf after the April 2010 explosion that sank the drill rig Deepwater Horizon and killed 11 men aboard. Oil spewed into the sea for nearly three months before a cap was placed on the BP-owned Macondo well, nearly a mile beneath the surface.

Scientists have previously confirmed that a plume of hydrocarbons from the well settled in the deep Gulf. White, a geochemist at Haverford College in Pennsylvania, said other data is still being analyzed.

“I think it’s going to take a while before we understand the long-term impacts of the spill,” she said.

Fisher said coral is a good bellwether because it is stationary, draws sustenance from the surrounding water and provides a refuge and breeding ground for other marine life.

“When a coral gets insulted, if you will, what it does is it produces a lot of mucus to try to get rid of that insult, kind of like we do reacting to dust or hay fever,” he said. The coral would normally shed that material, but in this case, it started to die, and the oil and other residues stuck to it.

What scientists saw wasn’t a “big puddle” of oil, “but there was enough in it that we could vacuum it off and fingerprint it,” he said.

“It certainly told us that we need to look around for more coral communities in the area and try to define the full footprint of the impact,” he said.