Story highlights

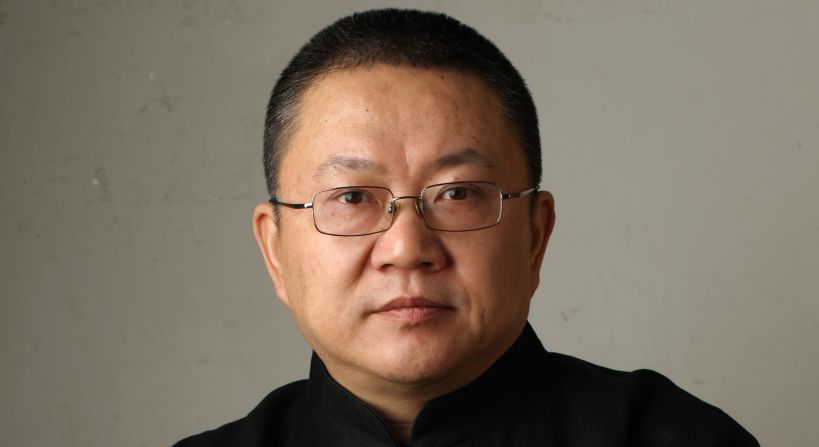

Wang Shu, 48, wins architecture's premier prize

Chinese designer uses recycled materials from historic buildings

He studied closely with artisans for almost a decade to learn about his materials

Wang studied exclusively in China, unlike many of his contemporaries

An architect who uses recycled building materials from historic buildings torn down to make way for China’s megacities has won architecture’s most prestigious international award, the 2012 Pritzker Architecture Prize.

Wang Shu, 48, whose Hangzhou-based firm Amateur Architecture Studio has just four permanent staff, was widely regarded as a long shot to win the $100,000 prize that has previously been awarded to celebrity architects such as Norman Foster and Frank Gehry.

“The fact that an architect from China has been selected by the jury to win the prize, represents a significant step in acknowledging the role that China will play in the development of architectural ideals,” said Thomas J. Pritzker, chairman of the Hyatt Foundation which sponsors the prize.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who studied overseas in the United States and Europe, Wang trained in China. He took the unusual step of taking on almost no commissions during the 1990s, instead learning about building materials by working closely with the kind of craftsmen normally shunned by office-bound architects.

“For myself, being an artisan or a craftsman, is being an amateur or almost the same thing,” Wang said in a press release, using the word in its true meaning as one who does something for love rather than money.

One of his most celebrated buildings, the Ningbo Historic Museum, used recycled materials collected from the nearby area to construct a modern building that paid homage to the past.

“My belief is that architecture should work hand in hand with time,” said Wang. “Sometimes I prefer to use less costly materials that can be replaced when damaged. Temporary, as I use the word, is not meant to mean disposable.”

He says the design process is similar to that of the traditional Chinese painter. He first studies the environment, looking at its orientation and geography. He then thinks about these things for a week without doing any designs. Then – as was the case with the Ningbo Historic Museum – the design begins to take shape in his mind.

“I design a house instead of a building,” he said. “One problem of professional architecture is that it thinks too much of a building. A house, which is close to our simple and daily life, is more fundamental than architecture.”

The Pritzker judges praised Wang’s ability to create architecture that is timeless, deeply rooted in its context and yet universal. One of the judges, Glenn Murcutt, a previous winner of the architecture prize, described Wang’s work as “mature,” avoiding the “sensational and the novel.”

“To look at the state of the profession, it would seem that anything is possible, and more often than not, we get anything!” he said.

Despite his growing reputation, Wang still has to struggle to gain acceptance for his idiosyncratic designs. The first step, he says, is to convince the government and the client, the second step is to marry the construction materials to the plan, and the third is to get those who will use the building to accept it.

“(This last step is) the hardest part of all, because the Chinese often think of a building as just a container whose functions can change at will,’ He added. “I can have no influence on this third stage.”