Story highlights

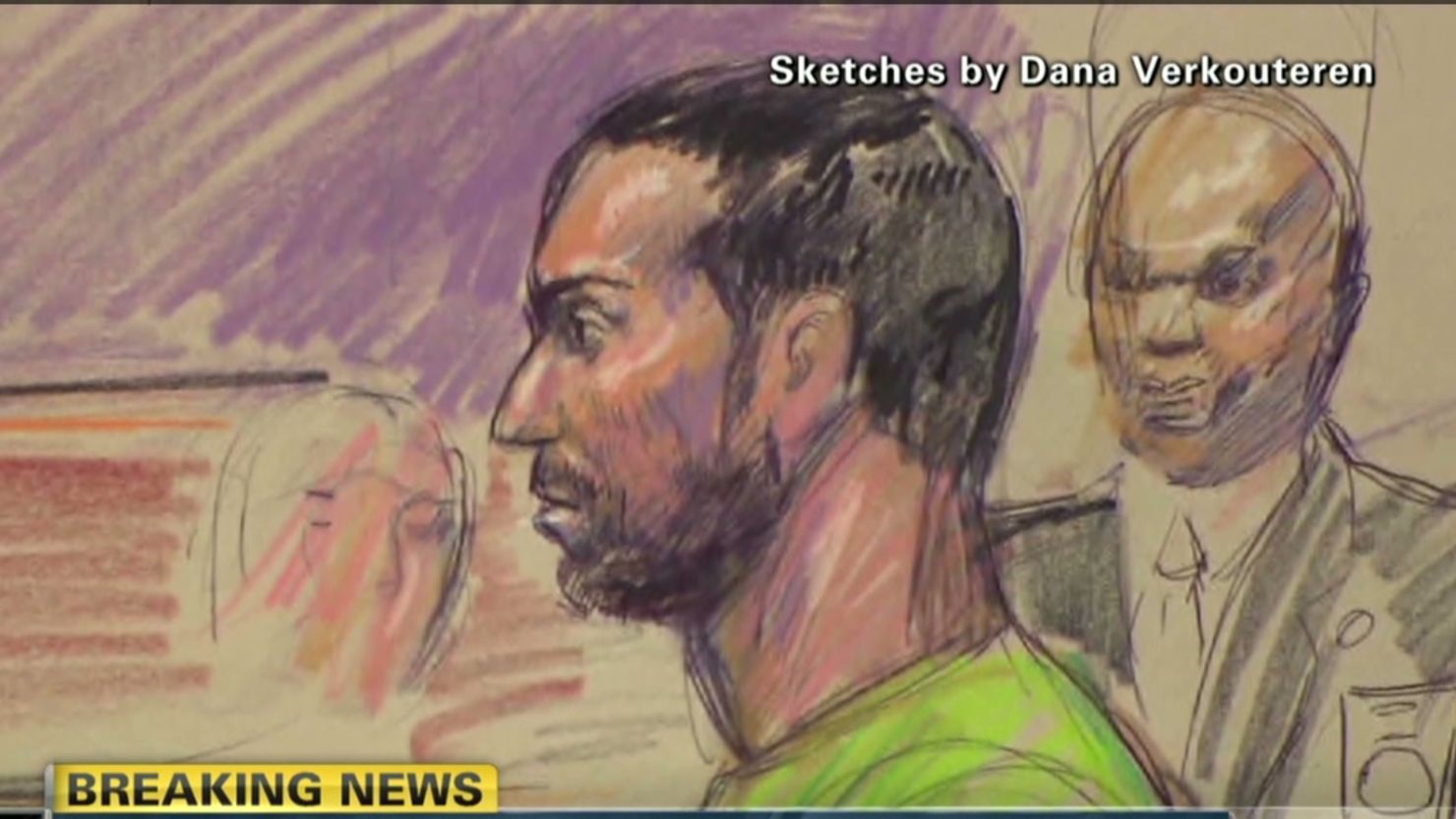

Amine El Khalifi is charged with attempting to use a weapon of mass destruction

He is alleged to have worked with others he believed to be al Qaeda operatives

Terrorism cases where individuals act alone are on the rise, experts say

In many ways, such cases are the worst nightmare of counterterrorism officials

The arrest of a 29-year-old Moroccan living illegally in the United States has focused attention again on the danger posed by “lone-wolf” terrorists.

Amine El Khalifi has been charged with plotting to carry out a bombing on the U.S. Capitol and attempting to use a weapon of mass destruction against federal property.

He is alleged to have worked with others he believed to be al Qaeda operatives, who provided him with a suicide vest and conducted a demonstration of explosives in a quarry in West Virginia, according to a Department of Justice affidavit.

Authorities: Suicide attack on U.S. Capitol foiled

For more than a year, undercover agents were in contact with El Khalifi after his intentions became known during an ongoing criminal investigation, according to one source.

According to the affidavit, an FBI informant brought El Khalifi, who was arrested Friday, to the attention of law enforcement in January 2011 after he told others at an Arlington residence that “the group needed to be ready for war.”

In many ways, such cases are the worst nightmare of counterterrorism officials: individuals acting alone, untraceable through any contacts with other terror suspects, capable of teaching themselves how to launch a terror attack.

In September, Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano said lone wolves “were harder to detect in part because by their very definition, they’re not conspiring with others, they may not be communicating with others, there’s very little to indicate that something is under way.”

In August, President Barack Obama said that a lone-wolf attack was “the most likely scenario that we have to guard against right now.”

The president told CNN’s Wolf Blitzer: “When you’ve got one person who is deranged or driven by a hateful ideology, they can do a lot of damage, and it’s a lot harder to trace those lone-wolf operators.”

He pointed to the case of Anders Breivik, who went on a bombing and shooting rampage in July in Norway, killing 77 people. No evidence has been uncovered linking Breivik to other conspirators.

A growing wave

The Norway attack showed how modern technological tools, especially the availability of vast amounts of information useful for bomb making and targeting, have made lone terrorists more dangerous than ever before.

In the past two and a half years, 11 of the 17 Islamist terrorist plots on U.S. soil involved individuals with no ties to terrorist organizations or other co-conspirators.

Responding to the arrest of El Khalifi, Sen. Susan Collins said she was alarmed by “the sharp escalation in the number of homegrown plots.”

She noted that data from the Congressional Research Service show that since May 2009, arrests have been made in connection with 36 ‘homegrown’ plots by American citizens or legal permanent residents of the United States.

El Khalifi had been in the United States illegally since 1999, according to the affidavit.

Before Friday, the most recent case was the arrest of Bronx resident Jose Pimentel, a Dominican convert to Islam, arrested in November after he started building a makeshift explosive device in a New York apartment from components he bought in local stores.

Pimentel, who acted alone, pleaded not guilty to charges he was plotting a terrorist attack on targets in New York City.

In late September 2011, Rezwan Ferdaus, a Massachusetts resident, was arrested by FBI officers after allegedly plotting to fly toy planes filled with high explosives into the dome of the U.S. Capitol.

Ferdaus, like El Khalifi, the Moroccan arrested Friday, believed he was working with other al Qaeda cell members. In reality they were FBI agents.

The pretense was such that when Osama bin Laden was killed, an agent somberly told Ferdaus: “my boss has just been killed … right now things are pretty rough.” Ferdaus has pleaded not guilty to the plot.

In February 2011, Khalid Aldawsari, a Saudi who arrived in the United States in 2008, was arrested and charged with plotting attacks against a number of targets, including the the Dallas residence of former U.S. President George W. Bush.

The FBI was alerted to the alleged plot after a North Carolina-based chemical supply company reported suspicions over an online purchase Aldawsari allegedly made. He has pleaded not guilty to attempting to carry out a bomb attack on U.S. soil.

Other lone-wolf plots included plans to blow up buildings in Illinois and Texas in September 2009, the November 2009 Fort Hood shootings allegedly carried out by U.S. Army Maj. Nidal Hasan, an alleged plot to bomb a tree-lighting ceremony in Portland in November 2010, and another aimed at blowing up an Army recruiting station near Baltimore the following month.

In September a senior U.S. counterterrorism official said lone assailants have been responsible for every deadly terrorist attack in the West since June 2009, when a U.S. serviceman was shot dead outside a recruiting station in Arkansas by a convert to Islam, Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad.

The role of the Internet and social media

Counterterrorism officials and analysts say the “lone-wolf” phenomenon is often fed by self-radicalization on the Internet.

“While there are methods to monitor some of this activity, it is simply impossible to know the inner thinking of every at-risk person,” the National Security Preparedness Group said in its report in September.

The proliferation of extremist websites in English or other European languages and the emergence of charismatic clerics such as Anwar al Awlaki have spread al Qaeda’s message more widely than ever before.

Online forums and chat rooms are even more influential. According to terrorism expert Marc Sageman, online discussions are much more likely to influence individuals than passively accessing radical online content.

Jose Pimentel, the alleged Bronx plotter, was particularly prolific online, maintaining a radical website in which he interacted with other extremists, according to authorities. Many apparently like-minded individuals posted messages on his YouTube site in the months leading up to his arrest, encouraging him in his online activities.

Like several others implicated in U.S. terrorism cases, Pimentel was in touch online with Jesse Morton, the co-founder of Revolution Muslim, a pro-al Qaeda group based in New York that maintained an extensive online presence. Morton pleaded guilty to “communicating threats” earlier this month, but there is no suggestion he knew of Pimentel’s alleged plot.

Accused Fort Hood shooter Nidal Hasan exchanged Internet messages with Awlaki, while Frankfurt shooter Arid Uka was Facebook friends with a number of known Islamist extremists in Germany.

Al Qaeda encouragement

Al Qaeda, partly out of necessity, has now thrown its weight fully behind “lone” terrorism. Its media production arm, As Sahab, recently released a video titled “You are Only Responsible for Yourself,” encouraging followers to carry out acts of individual terrorism in the West. In the recording, al Qaeda spokesman Adam Gadahn (born in Oregon) said it was easy for American al Qaeda sympathizers to go to a gun show and purchase an automatic assault rifle – without having to submit to a background check.

Al Qaeda’s Yemeni branch has been especially vocal in encouraging lone acts of terrorism. Before it went out of publication, its English language magazine Inspire had a section dedicated to helping terrorist sympathizers in the West carry out attacks, including bomb-making recipes. One recipe was called “How to Make a Bomb in your Mom’s Kitchen.”

Bronx bomb plotter Jose Pimentel had started making a pipe bomb based on the recipe when he was arrested, according to authorities. Pimentel went almost overnight from the “aspirational” to operational mode – the sort of rapid transition that gives counterterrorism officials “heartburn,” according to one counterterrorism official.

This Inspire magazine recipe was also allegedly downloaded by Naser Jason Abdo, a Muslim U.S. soldier who allegedly plotted to attack the Fort Hood military base before his arrest in July.

At a subsequent court appearance, he shouted “Nidal Hasan, Fort Hood 2009.” U.S. officials have said all the indications are that Abdo acted alone. He has pleaded not guilty to charges of possessing weapons and explosive materials.

Inspire magazine also heavily featured the writings of a Syrian al Qaeda-linked terrorist Abu Musab al Suri (real name: Mustafa Setmariam Naser) who pioneered the concept of individual terrorism in classes given to recruits in al Qaeda-linked terrorist camps in Afghanistan in the lead-up to 9/11.

“We ask the Muslim youth to be a terrorist. Why do we ask for such individual terrorism? First because secret hierarchical organizations failed to attract Muslims,” al Suri told recruits in Afghanistan in 2000, according to a videotape obtained by CNN.

Assessing the danger

Norway shooter Anders Breivik, for his part, made clear the advantages he saw in individual terrorism in a manifesto he posted online just before his attack.

“Solo Martyr Cells are completely unknown to our enemies and has a minimal chance of being exposed,” he wrote.

But so far, few lone-wolf terrorists have had the resources or skills to turn their plans into reality. Norwegian Breivik pointed out in his “manifesto” that his Norwegian roots, integration into society and deep financial pockets helped him advance his plot.

Breivik also showed great discipline and method in his planning. He was able to teach himself how to make an explosive device by online research and experimenting at a remote farm.

But making bombs out of chemicals available in the West has been seen as tricky and dangerous by Islamist militants plotting terrorist attacks, because of how unstable many of these substances are.

Breivik’s own document underlined the risk involved in making bombs out of readily purchasable chemicals. “30% chance of blowing yourself up,” he wrote above a recipe for an explosive substance he included for followers.

Bomb-making manuals produced by al Qaeda and its sympathizers tend to contain many errors, according to Sidney Alford, a British explosives expert who has reviewed many such manuals, making following their instructions hazardous.

“The overall quality of the documents that I’ve seen so far has been pretty low, but some of the content is certainly technically viable and they do contain, among some pages of rubbish quite practical means of causing havoc,” Alford said.

Countering the threat

The Obama administration believes the general public can play a key role in protecting against plots by lone terrorists.

“When people see something and they say something, that helps us with the lone actor scenario,” Napolitano said. She cited the example of the gun store owner who reported purchases being made by Naser Abdo near the Fort Hood base before his arrest in July.

Counterterrorism analysts say that outreach by U.S. law enforcement into Muslim communities is key in providing early warnings of threats. U.S. law enforcement agencies have also kept a watchful eye over individuals who may be moving toward violent extremism. Warning signs include ties individuals may have developed with known Islamist radicals or online interaction through jihadist websites.

Undercover agents and informants have also played a key role in helping the FBI and other U.S. law enforcement agencies uncover threats. The New York Police Department has developed the most extensive informant network in the country and has the largest number of undercover police officers assigned to terrorism cases.

The NYPD has also developed a Cyber Intelligence Unit in which undercover “cyber agents” track the online activities of suspected violent extremists and interact with them online to gauge the potential threat they pose. The unit has played a key role in several recent terrorism investigations including that of Abdel Hameed Shehadeh, who authorities allege attempted to travel overseas to Somalia to fight Jihad.

“By monitoring his activity on radical websites, the NYPD were able to build up a picture of his radical trajectory which was invaluable to the investigation,” a senior U.S. counterterrorism official said. Shehadeh, who was arrested in Hawaii in October 2010, has yet to enter a plea to charges of lying to authorities in a matter involving international terrorism.

The use of undercover agents has proved controversial in some cases. In several cases, agents have pretended to sympathize with solo plotters and in some cases have provided them assistance in order to obtain evidence to bring prosecutions. In these plots, rather than believing they were acting alone, the solo terrorists appeared to believe they were part of a conspiracy.

In El Khalifi’s case, his main contact and another man provided him with a MAC-10 automatic weapon and suicide vest to carry out the attack and drove him from North Virginia to a parking deck near the Capitol on Friday. In such cases, law enforcement agencies tread a fine line between establishing a suspect’s intentions and allegations of entrapment.

Terrorist loners

The most difficult individuals to track are those who have no communication with other Islamist extremists, either in person or online. Raffaello Pantucci, an associate fellow at the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, says that “rather than interacting online, such individuals passively soak up al Qaeda’s message and decide to take action into their own hands.”

Several such cases have emerged in the West in recent years. In April 2008 Andrew Ibrahim, a young white English student who had converted to Islam was arrested as he prepared explosives to carry out a suicide bombing at a shopping center.

Ibrahim, who was convicted of the plot, had no known interactions with other Islamist extremist, and was one of the few homegrown terrorists who managed to make a viable explosive device without formal training.

“Fortunately these loner cases are still a relative rarity,” Pantucci said.