Editor’s Note: This story is part of a series looking at the violence tied to Mexican drug cartels, their expanding global connections and how they affect people’s daily lives.

Story highlights

After passing a rigorous background check, Juan Andres received a special pass

The pass expedited his daily trip across the U.S.-Mexico border

He and other pass holders became victims of a drug cartel plot, officials say

Andres (not his real name) spent six months in prison, accused of drug smuggling

Every weekday, Juan Andres drives across the U.S.-Mexico border from his home in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, to the University of Texas at El Paso.

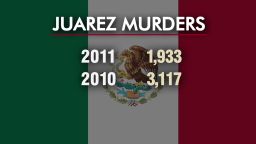

The three-and-a-half-mile commute takes him a world away from a major flashpoint in Mexico’s drug cartel war, away from a city with one of the world’s highest murder rates.

Andres, who agreed to speak to CNN under the condition that his name was changed, has always been keenly aware of his and his family’s safety while living in Juarez.

“The city was already pretty dangerous. We tried not to go to restaurants and things like that where [kidnappings] could happen,” he said.

A few years ago, Andres walked away from his career as an optometrist in Mexico to follow his passion: music.

“It was not a hard decision because music is something that I always wanted to do,” said the father of two, who is in his 30s.

To expedite his commute to the University of Texas at El Paso, where he studies music education, Andres received a special pass from U.S. Customs and Border Protection after passing a rigorous background check. Applicants have their fingerprints taken and must complete an in-person interview with a Customs and Border Protection officer. They cannot have any previous criminal history.

The SENTRI (which stands for Secure Electronic Network for Travelers Rapid Inspection) pass allowed Andres to waive the standard vehicle check at the border crossing. Most of the time, the border guards just peered inside his vehicle and waved him through.

Authorities were certain that he posed little to no risk of bringing drugs or weapons across the border. What they didn’t know was some of these special pass holders, including Andres, were being targeted by Mexican drug cartels, officials say.

“It was a nightmare, like suddenly being in a nightmare,” Andres said. “I [asked] God, ‘Why did you allow something like this to happen?’ ”

‘I knew it wasn’t right’

Living across the U.S. border in Ciudad Juarez, Andres knew the dangers of getting mixed up with drug cartels. He says he did his best to avoid them, staying away from malls and crowded areas where cartels are known to scout potential victims.

“I was working and studying a lot, so I didn’t have a lot of free time,” he said about his life before last fall.

In Ciudad Juarez, mutilated bodies are often left as warning signs to rival gangs. Despite a recent dip in the homicide rate, many residents still live in fear as police seem virtually helpless.

Gunmen ambush ambulance in Ciudad Juarez

On the morning of November 16, 2010, Andres drove his 2007 Ford Focus to the Stanton Street Bridge border crossing as he’d done every day for years.

On that day, Customs and Border Protection agents singled him out for a random search and discovered two bags of marijuana in the trunk of his car. He told the agents he had no idea how the drugs got there, but because there was no evidence that his trunk had been tampered with, he was arrested and detained.

“I knew it wasn’t right, I didn’t know what it was” he says, referring to the two black duffel bags agents found. “I was so afraid. … All I was thinking was, ‘How could that happen?’ I had no clue.”

Andres was held on the U.S. side of the border in isolation, and interrogated.

“I was afraid of what could happen to my family. I was trying to figure out who could’ve done that, and nothing came to my imagination. We really didn’t have enemies or knew people who were involved in that,” he said, referring to the marijuana. “I wasn’t working, was completely dedicated to school, my routine was going to school, coming home and doing homework.”

Hours later, Andres was able to call his brother, who then called his wife.

“She was scared. We didn’t know who did it, so we needed to get my wife out of the house,” he said.

Andres’ wife took their two young girls and went to stay with his brother in the United States while they waited to hear her husband’s fate.

Six months in jails

SENTRI pass holders can use dedicated lanes when crossing the border and have to comply with specific requirements, including an empty trunk.

Andres says he was certain there was nothing in his trunk when he headed across the border last year.

“The night before, I went to buy groceries, [and] I took all the groceries out [of the trunk],” he recalled. “I knew there was nothing there.”

Andres was charged with drug possession with the intent to distribute. He spent six months in various U.S. jails awaiting trial.

“It was really difficult to be there, knowing you’re surrounded by criminals. I tried not to talk to people there. Sometimes, it was scary because of the gangs. … It was depressing.”

He could’ve taken what’s called a “safety valve” plea – it’s an option for first-time drug trafficking and drug possession offenders with little or no criminal history.

Andres maintained his innocence and instead opted for a jury trial, hoping his peers would be able to see the truth. But they didn’t.

On May 10, Andres was found guilty of possession and intent to distribute marijuana. He faced up to three years in prison. Had he had a criminal record, he could’ve been sentenced to up to 20 years in prison.

How the scam works

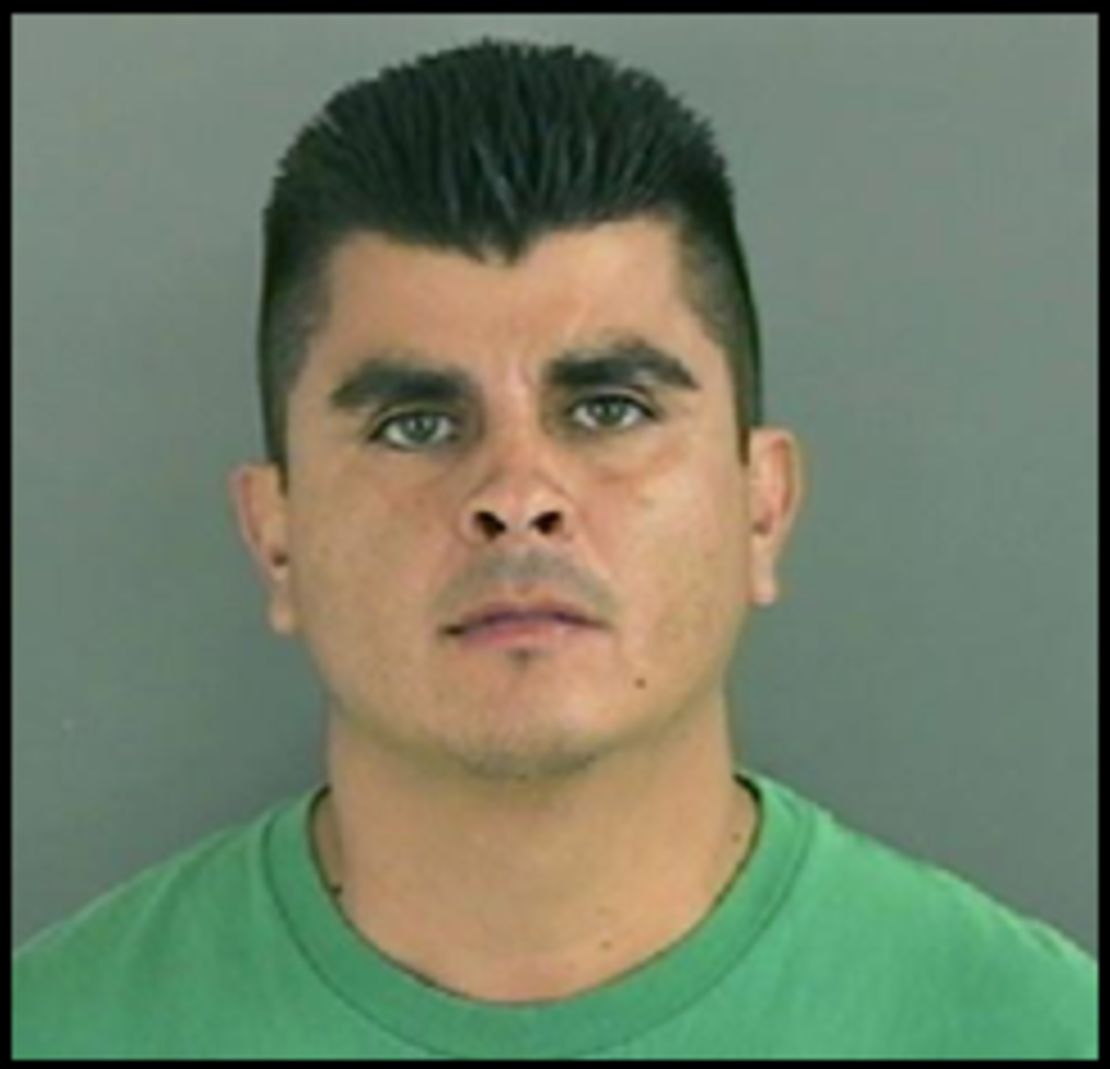

Drug cartels were well aware of the SENTRI pass system and concocted a plan to take advantage of it. Jesus Chavez and Carlos Alberto Gomez, both Mexican citizens living in Texas, were recently accused in a 20-page criminal complaint of doing just that.

According to the complaint, Chavez and Gomez allegedly paid lookouts to monitor SENTRI pass drivers – noting the time of day, as well as the make, model and color of their cars – as they drove over the bridge.

The lookouts targeted students and professionals who typically have consistent routines.

Once they identified a possible target, they followed the car as it returned to the Mexican side of the border. Then, they approached the car at night, copied the vehicle identification number (VIN) off the dashboard and gave the number to Chavez and Gomez.

They also planted GPS tracking devices on the car so they could monitor its movements between Juarez and El Paso.

The complaint alleges that Chavez and Gomez took the VIN to a Texas-based locksmith who had access to key code sources for the vehicles. With that information, the locksmith made two keys for each vehicle – one for Chavez and Gomez, and the other for Juarez-based accomplices.

The co-conspirators allegedly used their copy of the key to unlock the trunk of the target vehicle at night and place two duffel bags inside. The bags contained about 60 pounds of marijuana each and were both secured with zip ties.

The unsuspecting driver transported the drugs across the border unknowingly, and according to the complaint, Chavez and Gomez retrieved the drugs using their key once the driver was in the United States.

It was a simple, effective plan. But there was one problem: All the cases had striking similarities. And that caught the eye of a judge – but not until after innocent people, like Andres, had been convicted of smuggling drugs.

‘A common pattern’

Three days after his conviction, Andres was called back to court for a status hearing.

“That’s when I found out my lawyer had filed a motion for acquittal,” Andres said. “[The judge] said there had been similar cases to mine, [and] he told the prosecution to investigate.”

Senior U.S. District Judge David Briones, a 17-year judicial veteran, had noticed the pattern in the cases.

“I got information about [District Judge Philip R.] Martinez’s trial this week with almost the exact same facts: Two bags in the trunk, each with about 50 pounds tied together, and the individual was again inspected at the [commuter] lane,” Briones told Andres’ attorneys and the prosecutors at the status hearing that afternoon in May.

“I, quite frankly, think that an injustice has been done,” he said.

The judge dismissed the case against Andres, and he was released that day.

“When the judge dismissed [the case], I thought he really was wise,” Andres said. “How could he see all the things that surrounded it – the previous cases, the lack of evidence? I was really impressed to hear those words from his mouth. I’m really thankful for the wisdom he showed.”

Six weeks later, the charges against him were dismissed. By then, the judge had alerted the FBI, which had launched an investigation. In late July, federal investigators issued a criminal complaint.

Andres was one of at least five so-called “blind mules” identified in that 20-page federal complaint who were used by cartels to traffic drugs.

Others include a fourth-grade teacher and a sports medicine doctor. The blind mules had a few things in common: The bags were all secured the same way, each contained roughly the same amount of marijuana, and most of those caught drove a Ford. (The key code sources needed to create duplicate keys were much easier to access for Fords than for other types of vehicles, according to the complaint.)

FBI Special Agent Michael Martinez says the cartels’ cunning didn’t completely surprise him.

“We haven’t been made aware of anything like this [before],” he said. “[The cartels] are getting very creative, this was something relatively new.”

The investigation is ongoing, and Jesus Chavez’s alleged co-conspirator, Carlos Gomez, remains a fugitive. Efforts to reach a lawyer for Chavez, who’s in federal custody, were unsuccessful.

Despite the extensive vetting and background checks, sometimes those with criminal intent get by. U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials reported last week that a 30-year-old U.S. citizen and SENTRI pass holder allegedly attempted to cross the border from Tijuana, Mexico into southern California with nearly 54 pounds of methamphetamine in his car.

Despite being a free man with a cleared name, Juan Andres is still haunted by his experience.

“Being at school was really, really strange again. Seeing my friends who were taking class with me, and now they were ahead, was hard,” he says.

Not knowing if he was still being spied on weighed on him: “I was afraid for the first day of school, afraid of leaving the parking garage.”

And while six months of incarceration have affected the jazz lover’s level of saxophone playing, he doesn’t hold a grudge.

“I think the very important thing is we didn’t hold resentment or anger or anything like that. It wasn’t my fault; there was no way I could’ve avoided that. We take it like, ‘things happen.’ ”