Editor’s Note: This is the second in a weekly series on characteristics of creativity. Last week’s piece, on the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson, is here. Next Saturday’s piece will focus on the multitalented Paul D. Miller (aka DJ Spooky, That Subliminal Kid) and the ability to cross genres.

Story highlights

Jennifer Egan won a Pulitzer for her novel "A Visit from the Goon Squad"

First draft of works is always "terrible," she says -- but she improves it, over and over again

Failure paves way to creativity: Focus on long-term success, learn from mistakes

Egan describes road to success as "incremental"

When Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jennifer Egan writes a novel, it may go through 50 or 60 drafts.

The first one begins simply. She sits down with a legal pad and an open mind, deliberately creating by hand. She attempts to write about a half-dozen pages a day. At some point, the first draft is done.

Then comes, as she puts it, the “unpleasant tasks.”

She types the whole thing. She reads it. Almost invariably, she says, “it’s terrible.” But in her review, she gives herself concrete ways to fix it – edits, outlines (the one for her book “Look at Me” ran to 80 pages), discussions with other writers. All of which leads to more drafts, more frustration, more refinement.

Egan knows what she’s in for.

“The key is struggling a lot,” she says.

The struggle, of course, is often about fear: the fear of getting it wrong, of hitting a dead end, of wasting time. Of failing.

Failure. It’s such an ugly word, isn’t it? It reeks of cancer, of loss: the sense that what once went wrong cannot be set right, that the world has come to an end, that failures are failures forever – that it’s not just the project that failed, but you. Successful people, we imagine, are somehow blessed with more optimism, bigger brains and higher ideals than the rest of us.

But it’s not true. Successful people – creative people – fail every day, just like everybody else. Except they don’t view failure as a verdict. They view it as an opportunity. Indeed, it’s failure that paves the way for creativity.

John Seely Brown is the former head of the Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), the Xerox lab responsible for digital printing, the computer mouse and Ethernet. He says “trafficking in unlimited failure” let PARC’s employees invent once-unimaginable technologies.

“My mantra inside PARC, which was never particularly appreciated in corporate headquarters, was at least 75% of the things we did failed,” he says.

Investment manager Diane Garnick, who taught a course on failure at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, put it succinctly. “We learn more from our failures than we could ever learn from our successes,” she told the site Bodyhacker.

Ups and downs

Egan, 49, would probably be described as a success. The Chicago-born, San Francisco-bred author won the Pulitzer last year for her novel “A Visit from the Goon Squad.” Her short stories have appeared in The New Yorker. She’s a regular contributor to The New York Times Magazine and the author of several other highly esteemed works, including “Look at Me” and “The Keep.”

Her demeanor is welcoming and considerate, but her eyes miss nothing, displaying a determined curiosity. She works from a cozy Brooklyn brownstone she shares with her husband, theater director David Herskovits, and their two grade-school sons, whose exuberant artwork decorates the ground floor.

Her life has had its ups and downs, but she retains an even-keeled perspective, describing her creative growth as “incremental all the way.”

Such a long-term outlook is key to coping with failure. Not necessarily getting it right the first time? That’s fine – you’re recording something, anything, so that other ideas can rise to the surface. Hitting a dead end? Take a breath, take time to understand and try something else. That’s your creative drive kicking into gear.

Robert Epstein, a former editor of Psychology Today and founder of the Cambridge Center for Behavioral Studies, likens the process to being stuck in a locked room. The doorknob isn’t responding. You turn it, you jiggle it, you lift it. Nothing.

“When you’re ineffective and you can’t turn that knob, lots and lots of different behaviors and thoughts and ideas all pop up simultaneously, more or less – and that’s the stuff of creativity,” he says. “That’s where the inner connections occur.”

The wonderful thing about such creative sparks is they’ll feed off one another. The terrible thing is that emotions might take over and reduce you to mush. Epstein observes that the person in the locked room eventually starts banging on the door and, if left long enough, cries for his or her mother.

Egan can relate.

When she was a teenager, she took a year off between high school and college to travel in Europe. It was great at first. “The exaltation of being propelled alone into a totally alien place was really remarkable,” she says.

But, eventually, the aloneness became too much. She suffered panic attacks and ended up calling her parents to help get her home.

So Europe didn’t work out, not in the way Egan imagined. On the other hand, she found a new passion: writing. She kept a journal – she still has it – and the pleasure she got from developing her thoughts on paper prompted her to consider writing as a career.

Having ‘grit’

That’s not what she thought she’d be doing while growing up. She considered a career as a doctor – one of her grandfathers was a surgeon – but a teenage bout of squeamishness ruled that out. As for the creative arts, “I wasn’t a standout amazing kid,” she says. “My creativity has always felt like a secret to me.”

However, being creative doesn’t require being Mozart. Stubbornness and practicality play a role, too. Studies of grade school and college students indicated they owed their academic success to such characteristics as curiosity, self-control and what psychology professor Angela Duckworth termed “grit” – even if they were of average intelligence.

Besides, failure seems to loom around every corner, especially for creative types like writers. “I think it’s totally rational for a writer, no matter how much experience he has, to go right down in confidence to almost zero when you sit down to start something,” author John McPhee once observed.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing if it’s kept in perspective.

In 1989, when she was 27, Egan sold a short story to The New Yorker, then and now one of the most prestigious magazines in the world. But there was a catch. Her story, “The Stylist,” was much better than anything else she had written – and she knew it. Her other submissions met with disappointment and rejection.

She felt like – that word again – “a failure.”

“That story really hung over me, and it cast a very long shadow,” she recalls. “I thought I’d never top it.”

How to combat such a feeling? Keep moving.

Egan worked to improve. She wangled a residency at the artistic retreat Yaddo in upstate New York. She went to conferences. She even revived a novel she’d attempted years earlier. It all contributed to her development. By 1995, after building up credits in a variety of publications, she was back in The New Yorker and had published a short story collection as well.

Plugging away – with no guarantee of success – is not advice people like to hear. Iain Roberts, a principal with the design consultancy IDEO, says some clients have to be educated that “you have to be OK with failing.” Clients naturally want to play it safe, but sometimes the most interesting ideas are out on the fringes. For example, he says, a cell phone provider might want to focus on established users, but what about trying to market to people who don’t own cell phones at all?

“It’s always a risk,” he says. But a necessary one: “If you’re not failing, you’re not pushing hard enough.”

Giving up is not the end

Has Egan given up on projects? Of course. She said there were four chapters of “Goon Squad” she tried to write but just couldn’t make work. She wasn’t into that part of the story, so why would her readers want to join her there?

“That’s different than being afraid of the material, or veering away from it but with a kind of excitement,” she says. “It’s just literally you’d rather do anything else.” The feeling for her, she adds, is like “the kiss of death.”

Some creative people never let go.

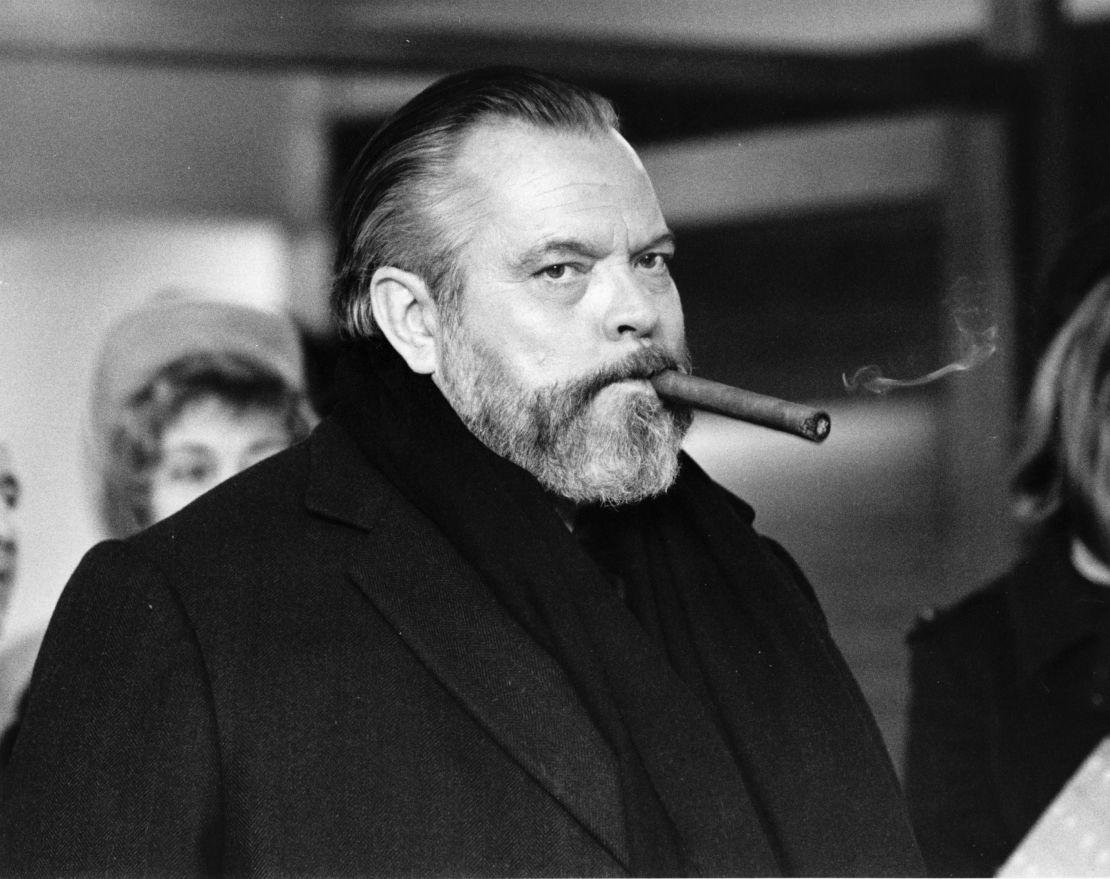

Orson Welles filmed “The Other Side of the Wind” in 1970; he kept tinkering with it right up until his death in 1985. It’s never been released.

Ralph Ellison labored over “Juneteenth,” his follow-up to “Invisible Man,” for years. The never-finished novel was finally published in 1999, five years after Ellison’s death, after being edited down from a 2,000-page manuscript.

Axl Rose spent almost 15 years on Guns N’ Roses’ “Chinese Democracy,” working on it long after the other original members had left the band. It was finally released in 2008.

Giving up can also be part of the creative process, says Dean Keith Simonton, a psychology professor at the University of California, Davis, and a creativity expert.

“Sooner or later, creators have to learn when an idea is going nowhere,” he says.

But, he cautions, that point is hard to identify.

“The error is more often in the opposite direction: Not giving a new idea a sufficient chance for development. It is not easy to tell in advance which is going to pan out and which not,” he says. The uncertainty cuts both ways: “Edison spent more time and money developing a means for separating iron ore than he did on the electric light bulb. The former was a dismal failure, the latter a brilliant success.”

Egan agrees assessing progress isn’t easy.

“A lot of it is trying to understand what kind of dead end it is, because they aren’t all the same,” she says. “With ‘The Keep,’ I was essentially at a dead end for the first many months of working on it, because I couldn’t find a voice for it. And if you don’t have a voice, you’ve got nothin’. You can try every bell and whistle and good idea in the world, but if the book doesn’t have a voice, you don’t have a book.

“But for some reason I kept hammering away at it, which certainly in retrospect could have been a terrible waste of time if I hadn’t found a way,” she said.

If you decide the work has merit, there comes a point when you take what you have. Eventually the time for major creativity recedes and you’re just trying to get to the finish line – proofreading, refining, going over details. It can be grueling.

“At that point, disgust and ennui sets in,” Egan admitted. “But I have a job to do. I can’t walk away. I have a desire to make it better that drives me.”

And then it’s time to do it again, to climb back on the high wire and start from scratch. Scary? Absolutely. Failure is always scary. But, says Egan, it’s where creative energy comes from: The awards and acclaim are wonderful, but the joy comes from the freedom she feels in trying the unusual.

Indeed, she says her recent books have been much more rewarding to write because of their challenges.

“And since then,” she says, “I’ve had a lot more fun.”