Editor’s Note: This article begins an occasional series looking at the violence tied to Mexican drug cartels, their expanding global connections and how they affect people’s daily lives.

Story highlights

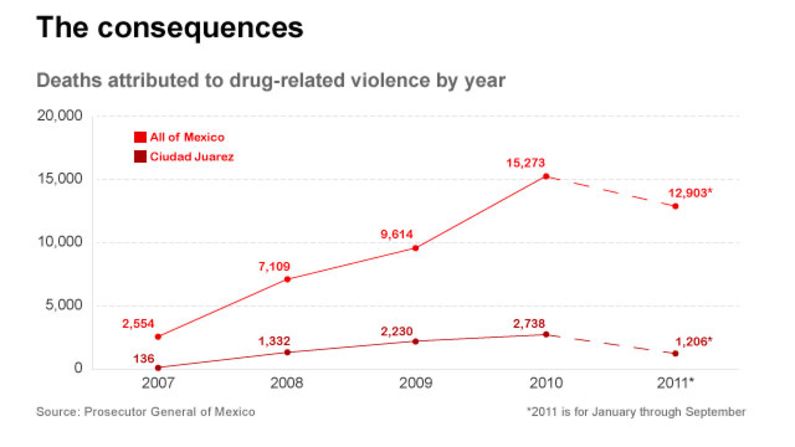

Since December 2006, nearly 48,000 people have been killed in drug-related violence in Mexico

Mexican cartels make billions of dollars a year, much of their profits in the U.S.

The bloodbath could threaten the survival of the Mexican state, and American national security

There are kingpins with names like the Engineer, head-chopping hit men, dirty cops and double-dealing politicians. And, of course, there are users – millions of them.

But the Mexican drug war, at its core, is about two numbers: 48,000 and 39 billion.

Over the past five years, nearly 48,000 people have been killed in suspected drug-related violence in Mexico, the country’s federal attorney general announced this month. In the first three quarters of 2011, almost 13,000 people died.

Cold and incomprehensible zeros, the death toll doesn’t include the more than 5,000 people who have disappeared, according to Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission. It doesn’t account for the tens of thousands of children orphaned by the violence.

The guilty live on both sides of the border.

Street gangs with cartel ties are not only in Los Angeles and Dallas, but also in many smaller cities across the United States and much farther north of the Mexican border. Mexican cartels had a presence in 230 cities in the United States in 2008, according to the U.S. Justice Department. Its 2011 report shows that presence has grown to more than 1,000 U.S. cities. While the violence has remained mostly in Mexico, authorities in Arizona, Georgia, Texas, Alabama and other states have reportedly investigated abductions and killings suspected to be tied to cartels.

Mexican black tar heroin (so called because it’s dark and sticky), is cheaper than Colombian heroin, and used to be a rarity in the United States. Now it is available in dozens of cities and small towns, experts say. Customers phone in their orders, the Los Angeles Times reports, and small-time dealers deliver the drug, almost like pizza deliverymen.

Traffickers are recruiting in the United States, and prefer to hire young. Texas high schools say cartel members have been on their campuses. Most notoriously, a 14-year-old from San Diego became a head-chopping cartel assassin.

“I slit their throats,” he testified at his trial, held near Cuernavaca. The teenager, called “El Ponchis” - the Cloak - was found guilty of torturing and beheading and sentenced to three years in a Mexican prison.

For more than a decade, the United States’ focus has been terrorism, an exhausting battle reliant on covert operatives in societies where the rule of law has collapsed or widespread violence is the norm. The situation in Mexico is beginning to show similarities. In many border areas, the authority of the Mexican state seems either entirely absent or extremely weak. In September 2010, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said cartel violence might be “morphing into or making common cause with what we would call an insurgency.”

If cartel violence is not contained in Mexico, which shares a nearly 2,000 mile border with the United States, the drug war could threaten U.S. national security and even survival of the Mexican state.

How much is enough?

For most of us, Mexico is reduced several times a week to a sickening barrage of horror flick headlines. Thirty-five bodies left on the freeway during rush-hour in a major tourist city. A person’s face sewn onto a soccer ball. Bodies found stuffed in barrels of acid. Heads sent rolling onto busy nightclub dance floors.

What could explain such savagery?

Traffickers don’t have a political or religious ideology like al Qaeda.

The answer, some experts say, is a number. Something like $39 billion.

That’s the top estimated amount Mexican and Colombian drug trafficking organizations make in wholesale profits annually, according to a 2009 Justice Department report, the latest year for which that calculation was available. The department’s 2011 report said that Mexican traffickers control the flow of most of the cocaine, heroin, foreign-produced marijuana and methamphetamine in the United States.

There are seven cartels in Mexico vying for control of smuggling routes into the United States, a bountiful sellers’ paradise. South of the border it costs $2,000 to produce a kilo of cocaine from leaf to lab, the DEA said. In the U.S., a kilo’s street value ranges from $34,000 to $120,000, depending on the ZIP code where it’s pushed.

“How much is enough to the cartels? How many billions justify how many deaths to them?” said DEA special agent and spokesman Jeffrey Scott. “Mexico is their home, too. Their families live there. At what point does the violence cripple their ability to conduct business?”

Scott has been with the DEA for 16 years. Between 2006 and 2011, he led a Tucson, Arizona, strike force that fought smugglers bringing tons of methamphetamine, marijuana, heroin and cocaine across the border. By the time the drugs reach the low-level street dealer, they have been through many middle managers in the cartels’ purposely confusing web of workers.

“The people who are arrested will sometimes say, ‘Sinaloa who?’” he said, referring to the cartel that originated in the Mexican Pacific Coast state and has the strongest presence in the United States.

Dealers usually don’t know or care where their product comes from, Scott said. He said he doubts the tens of millions of Americans who use illegal drugs do, either.

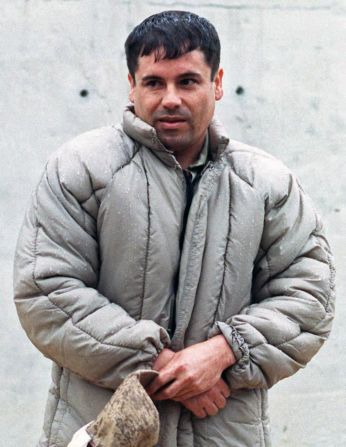

Get Shorty

From foot to head he is short/But he is the biggest of the big

If you respect him, he’ll respect you

If you offend him, it will get worse

– Lyrics to narcocorrido “El Chapo” by Los Canelos de Durango

“El Chapo” (Shorty) is the boss of the Sinaloa cartel. In his last-known photo, the 5 foot 6 inch son of a poor rural family wears a schoolboy haircut and a plain-colored puff-coat. Despite having virtually no formal education, Forbes estimates Joaquin Guzman Loera is worth $1 billion. This month the U.S. Treasury declared him the most influential trafficker in the world. He has eluded capture for more than a decade, is known for coming up with original ways to smuggle, like putting cocaine in fire extinguishers, and is suspected of helping Mexicans and Colombians launder as much as $20 billion in drug profits.

The legend of “El Chapo” began to grow when he escaped, reportedly on a laundry cart, from a Mexican prison in 2001. He seemed even more untouchable last summer when his 20-something beauty queen wife (who has dual nationality) crossed into California to give birth to twins. The birth certificates leave blank the space for the father’s name, and she apparently hustled back across the border.

It’s anyone’s guess where El Chapo is. Mexican President Felipe Calderon wondered last year if he was hiding out in the United States.

Guzman is the drug war. Perpetuating the image of the bulletproof bad guy keeps it alive.

YouTube is full of narco snuff. Those with weak stomachs should avoid the wildly popular El Blog del Narco, which posts gory photos of killings and confessions by drug lords. Cartels make their own movies, glorifying the business. The films are sold in street markets in Mexico and the United States.

Some say it’s no coincidence that the first beheadings of Mexican police officers occurred in 2006, when videotapes of al Qaeda beheadings were shown on Mexican television.

Since then, headless corpses have become a cartel calling card. In a single week in September, a sack of heads was left near an Acapulco elementary school and a blogging reporter’s headless corpse was dumped in front of a major thoroughfare in the Texas border town of Nuevo Laredo. Her head, along with headphones and computer equipment, was found in a street planter.

A note left at the scene, one of dozens of journalist killings in the past five years, read: “OK Nuevo Laredo live on the social networks, I am La Nena de Laredo and I am here because of my reports and yours …”

The message was signed with several Z’s, indicating the slaying was the work of another major cartel, the Zetas.

One of the first cartels to use the internet, the Zetas are perhaps the savviest propagandists in the drug war. They’re known for effective recruitment tactics.

A few years ago, they appealed to the destitute in a nation where the minimum wage is $5 a day, but millions have no work.

Banners were dropped from bridges in major cities.

“Why be poor?” the signs said. “Come work for us.”

The good old bad days

Desde que yo era chiquillo tenia fintas de cabron (Ever since I was a kid, I had the fame of a bad-ass)

ya le pegaba al perico, y a la mota (already hitting the parrot [cocaine] and doing dope [marijuana])

– El Cabron, a legendary narcocorrido, or narco ballad, released in 2005.

Feeding addiction has long been a part of Mexico’s relationship with the United States, first becoming a well-oiled operation during Prohibition when Americans crossed over to drink and get high and Mexicans sent marijuana and alcohol to speakeasies in the States.

During this era, narcocorridos, or drug pop ballads glorifying kingpins, became popular. The accordion-based anthems were danceable, fun. Today the songs are no longer so amusing.

Between 2006 and 2008, more than a dozen performers have been murdered. Cartels have held some balladeers hostage for days, forcing them to entertain partying crews. Some state and local Mexican governments have tried to ban the music, but the effort has only made the songs sexier. They shake butts from Cancun to Culiacan, and across the United States from Los Angeles to New York. Slain narco singers have been nominated for posthumous Grammys. (Watch narco singer Valentín Elizalde’s music video “A Mis Enemigos” which some speculate was an attack on the Gulf cartel and led to his murder.)

Narcocorridos have become death impersonating art, a symbol of just how unexpectedly dark the Mexican drug business has become.

The definition of a cartel is an agreement among competing firms. That was the old way for the Mexicans. Pay the cops and the politicians. Don’t kill anyone unless absolutely necessary and don’t make a mess of it.

Two scenarios made their thieves’ agreement possible.

For decades, Mexicans mainly transported cocaine for the Colombians or the Colombians sent the cocaine directly into the United States on planes or speedboats.

That changed in the 1990s when the United States tightened its choke on Colombia’s main smuggling point in the Caribbean and Florida and worked with the Colombian government to combat cartels and eliminate kingpins like Pablo Escobar.

The neutered Colombian cartels were then forced to rely on the Mexicans, who smuggled across much more vast and impossible to monitor areas like the border and the eastern Pacific Ocean.

Suddenly indispensable in their industry, the cartels in Mexico reacted like any ambitious corporation. They bought out every last possible competitor, ramping up bribes across the ranks of law enforcement and politicians. They advertised themselves to struggling working class people and the poor as a panacea amid all the government’s failures: Cartels were the private-sector alternative.

Within a few years, they gained unrivaled dominance in the global illicit drug trade.

The second scenario helping the cartels, some experts say, was rampant corruption within the PRI, or the Institutional Revolutionary Party, which ran Mexico for 72 years.

There were far fewer deaths and the cartels’ bottom line wasn’t threatened.

The PRI lost power in 2000 with the election of Vicente Fox, who led the opposition National Action Party.

Known for his cowboy hats, Fox made little of the cartels during his election campaign. But after meeting with American officials in the early days of his administration, he announced he wanted the traffickers gone.

The arrests of kingpins and key players followed, which prompted chaos within cartel ranks as commands were shaken. Cartel members fought amongst themselves and each other. The good old bad days ended.

A real war starts

La traicion y el contrabando (The treason and the contraband)

Son cosas incompartidas” (They are the same thing)

- Lyrics to “Contrabando y traicion” by Tigres del Norte

To understand the drug war, accept that it’s impossible to keep track of all its players. Accept that there are no white hats or black hats. There’s only grey. Fog.

There is, however, agreement among experts about when war was declared: In late 2004 in the border town of Nuevo Laredo, 10 minutes from Laredo, Texas.

The Sinaloa wanted this golden smuggling route.

Every year, more than 5 million cars, 1.5 million commercial trucks and 3.8 million pedestrians cross northbound from Mexico into the United States here, bringing with them a ton of hidden narcotics.

In 2004, Nuevo Laredo was controlled by the Gulf cartel, which was just as old and Corleone-esque as Sinaloa.

For help defending their turf, the Gulf hired a group of former Mexican special forces soldiers who called themselves Zetas after the federal police code for high-ranking officers, “Z1.”

The Sinaloa clan hired their own protection, a gang named Los Negros led by a blond-haired, blue-eyed American from Laredo. The man’s cohorts called him La Barbie.

The Zetas battled Los Negros with tactics befitting an elite military. They fired automatic weapons, launched RPGs and grenades. They shot at each other for more than a year. Local gangs jumped in. Civilians dropped.

Emboldened by their Nuevo Laredo victory, the Zetas formed their own cartel. As they went after other cartels throughout Mexico, the Zetas honed a reputation for sickening brutality, seeming to kill just because they can. They have been blamed for setting fire to a casino killing 52 people, shooting dead 72 migrants on a Tamaulipas farm in 2010, murdering and tossing into mass graves women and children and killing bloggers. In April 2011, the bodies of 190 people, some of them migrant workers, were found in a mass grave in the desert of Tamaulipas.

Officials say the Zetas have lobbed grenades into celebrating crowds and blown up a pipeline that sent “rivers of fire” into residential streets. They have terrorized cities that once seemed untouchable by the violence, including the port city of Veracruz and Mexico’s richest city, Monterrey, home to many international companies.

As the Zetas enacted their terror, that blond-haired, blue-eyed American leading Los Negros got angrier. La Barbie was Edgar Valdez, a Texas high school football star who worked his way into the Mexican underworld as a pot dealer. In 2005, the Dallas Morning News reported on a video showing four bound and bloody men, suspected to be Zetas, being interrogated off camera by a man believed to be Valdez.

A pistol comes into the frame, goes off and one of the men slumps. The video went viral. People around the globe started asking what was really going on in Mexico.

Journalist Ioan Grillo has been to more murder scenes than he can recall. His new book, “El Narco: Inside Mexico’s Criminal Insurgency,” includes interviews with hit men, gang members, government and law enforcement officials and people caught in the crossfire.

Grillo repeatedly returns to a single idea. Wars occur because people cannot feed their families. They happen because groups of people feel unimportant, disenfranchised, angry and broke. They want a piece of life. It only takes a few people with particularly hollow morals, capable of shutting off or suppressing guilt, to convince many that killing and dying in spectacular ways is tantamount to glory.

Jihadist groups, kamikaze squadrons, American street gangs, cartels. Their members were all kids at one point. Grillo writes that he has seen teenagers show up at murder scenes showing no grief. It has become routine. They pick up shell casings scattered on the ground and debate whether they’ve been fired from AK47s or M4s.

There are very few counselors in Mexico to help, and there is very little quality education outside the circles of the comparatively privileged few, he wrote.

Why wouldn’t a kid take 50 pesos to be a lookout, or 1,000 pesos to kill someone?

“I would love to see more money spent on these concerns,” Grillo said, “than on more military helicopters and soldiers gunning it out with the cartels.”

Fighting back

After he was elected president in 2006, the PAN’s Felipe Calderon took a page out of his predecessor’s playbook and declared war on the cartels. He had the Mexican military fan out across the country and fired hundreds of corrupt police officers. He even disarmed an entire town, saying that most of its police force was working for the cartels.

Plenty of narcos were arrested, and some extradited to the United States, but many thousands of people died. They included cartel members, police and civilians who were caught in the middle of a gruesome war.

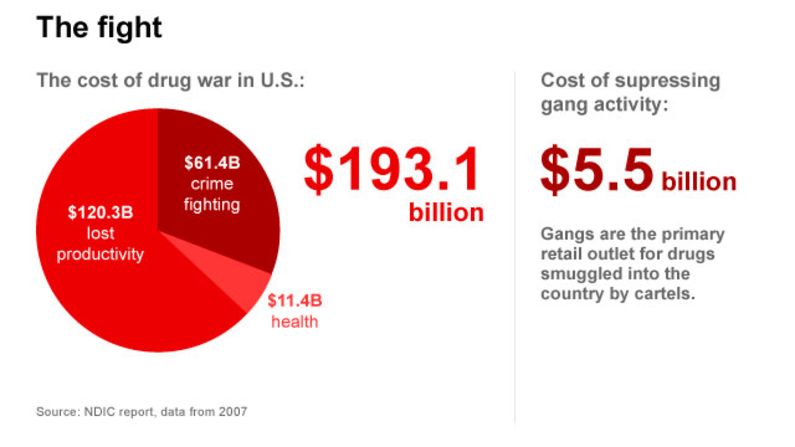

Calderon and President George W. Bush reached an unprecedented agreement to fight the cartels. The Merida Initiative (named after the Mexican city where the two met) included a U.S. pledge of $1.5 billion between 2008 and 2010. President Obama requested millions more for 2011 for the program. The program provides aircraft, inspection tools and other sophisticated drug-detecting technology to the Mexicans. It also funds drug counseling and prison rehabilitation programs.

To fight corruption, the United States has also pledged to give money to help train police in Mexico.

For its part, the Mexican government has passed legislation aimed at bolstering its judicial system, and in October 2010, Calderon formally requested a total reshaping of the police force in Mexico. The reform he proposed would create unified state police forces and eliminate municipal police, who federal officials have said are very susceptible to corruption because of their low salaries.

Observers say Calderon underestimated how many police and other law enforcement officers were on the cartels’ payroll when he came to power. As of March 2008, 150,000 soldiers had deserted. Traffickers, experts say, spent the Fox administration hunkering down, ingratiating themselves to communities, buying food and paying for medical bills, offering restless young people a sense of identity and hard cash.

And as Grillo has written, many people didn’t trust the police and the soldiers as they once did. Authorities were accused of widespread human rights abuses while on anti-cartel missions. Jose Luis Soberanes, president of the Mexican Human Rights Commission, testified in 2008 that his office had received complaints that police and soldiers had entered towns to rape and torture and kill, including shooting dead two women and three children in Sinaloa state.

The cartels had become Robin Hood to many, similar to Colombia kingpin Escobar. In his impoverished Medellin, Escobar built a soccer field and a school. He died in a gunbattle with agents in 1993. At the church Escobar built, some Colombians still come to worship him like a saint.

A Barbie, a fox and some piggies

“La Barbie” was arrested in August 2010 in Mexico, and smiled as he was paraded in front of the press. The green Ralph Lauren polo shirt he wore inspired an international fashion trend.

Calderon’s administration trumpets his arrest and others, and vows to keep fighting the cartels. But the president is a lame duck. Term limits prohibit him from running again in 2012.

Many expect the PRI, Mexico’s founding party that ruled for seven decades, to return to power in July’s elections.

Whoever wins the election will have to answer a critical question: whether to appease the cartels and try to negotiate with them or continue the all-out assault that Calderon launched.

Negotiating with traffickers played a role in Colombia, where religious figures and former guerillas led the talks, experts said.

But they also stress that Mexico is not Colombia, and this is not the late 1980s. Crime syndicates operate differently. Key players on both sides of the border have considerations unlike those during the Colombian crisis. Mexico, they contend, is far less likely to welcome close foreign involvement than Colombia did.

A solution also cannot come from only one side of the border. Former President Fox and other experienced leaders in Latin America have advocated legalizing the consumption of marijuana, saying it would cut the value of the cartels’ product. In 2011, the U.N.’s Global Commission on Drug Policy, which included Fox, recommended that governments experiment with drug legalization, especially marijuana.

Last fall, Texas Gov. Rick Perry, a candidate for the 2012 GOP presidential nomination, said he thought the drug war violence had become so dire that U.S. troops could be sent into Mexico. Drug trafficking in Mexico, he and others have said, fuels criminal organizations around the globe and feeds human and arms trafficking.

Perry had barely finished his thought before being pounced on by critics, many within his own party and especially his opponents: How would a limping U.S. economy pay for that? The United States was already involved in two wars.

Mexico has historically been highly averse to allowing a foreign force to fight on its soil, experts said. The idea of Team America swooping into its sovereign neighbor is offensive to many Mexicans. Consider the country’s national anthem, written after the 1840s Mexican-American War in which Mexico lost half its territory.

If some enemy outlander should dare

to profane your ground with his sole,

think, oh beloved Fatherland, that heaven has given you a soldier in every son

In 2009, the group Los Tigres del Norte were banned from performing a popular song titled “La Granja” at an awards ceremony in Mexico City.

The lyrics blast the Mexican government’s strategy against the cartels, a “Fox” who came to break plates on a farm. The animals got out “to create a big mess.”

The lyrics also suggest that America, Mexico’s No. 1 drug customer, is just as dirty.

The piggies helped out

They feed themselves from the farm

Daily they want more corn

And they lose the profits

And the farmer that works

Does not trust them anymore