Need to see a doctor? Get ready to pay more if the Senate health care bill becomes law.

Republicans in the Senate say they are trying to make health care more affordable for Americans by reversing the premium hikes wrought by Obamacare.

Under their plan, however, many Obamacare enrollees would see their monthly premiums go up. What's more, many consumers also would have to shell out a lot more money when they actually see a doctor or get treatment. That's because many would be covered by skimpier policies.

Related: McConnell to delay vote on health care bill

The Senate bill would hike health care bills in several ways. It would provide less government assistance to pay for premiums and out-of-pocket costs. It would tie subsidies to health insurance policies with higher deductibles. And it would allow insurers to shift more of the financial responsibility to policyholders in states that opt to waive certain Obamacare protections.

"There's no way the Senate bill can reduce consumers' net health insurance costs," said Robert Laszewski, a health care consultant. "When the government pays less, people have to pay more."

Let's look at how this would happen.

Less generous subsidies

The Senate bill would spend $408 billion less on federal subsidies to help people pay for coverage.

It would shut out more middle class folks from government aid by tightening the eligibility criteria starting in 2020. Only those earning up to 350% of the poverty level ($41,600 in 2017) would qualify for premium subsidies on the individual market, rather than the 400% threshold ($47,500 in 2017) contained in Obamacare.

Related: Mom fears for her child's health under GOP bill

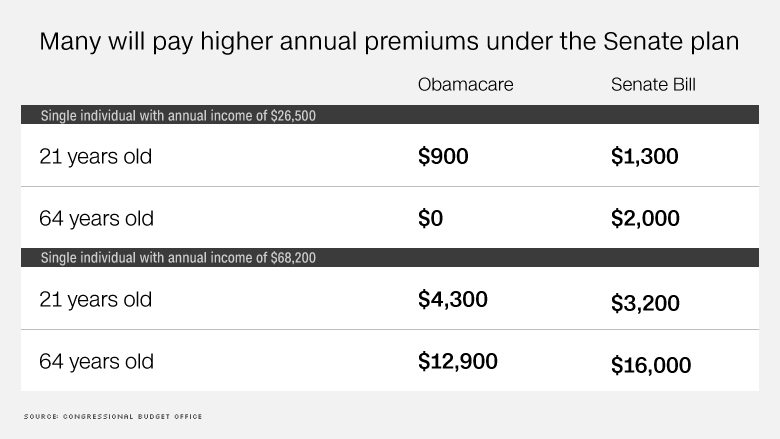

Also, it would provide less help to older consumers with moderate incomes. For instance, those in their 60s would have to pay up to 16.2% of their income toward premiums, compared to about 10% under Obamacare. And 50-year-olds would be responsible for 15.8% of the rate. (These folks would also face higher premiums because the legislation would let insurers charge them even more, compared to younger enrollees.)

As a result, most Obamacare enrollees would pay higher premiums for the benchmark silver plan under the Senate bill than under the current law, according to a non-partisan Kaiser Family Foundation analysis. Monthly premiums would be 74% higher overall in 2020, under the Senate bill, even after taking into account the premium subsidies.

Many enrollees would also have to pay more out of pocket to get care. The Senate would eliminate Obamacare's cost-sharing subsidies -- which reduce lower-income enrollees' deductibles and co-pays -- starting in 2020. Those with incomes closer to the poverty line currently have an annual deductible of $255, on average, compared to more than $3,600 under a standard silver policy.

Related: Who gets hurt and who gets helped by the Senate health care bill

The Senate plan would also slash federal funding for Medicaid, likely forcing states to curtail enrollment or benefits. The bill would give subsidies to poor Americans who don't qualify for Medicaid so they can buy policies in the private market. But experts say these folks wouldn't be able to afford the hefty deductibles and likely wouldn't sign up.

Higher deductible plans

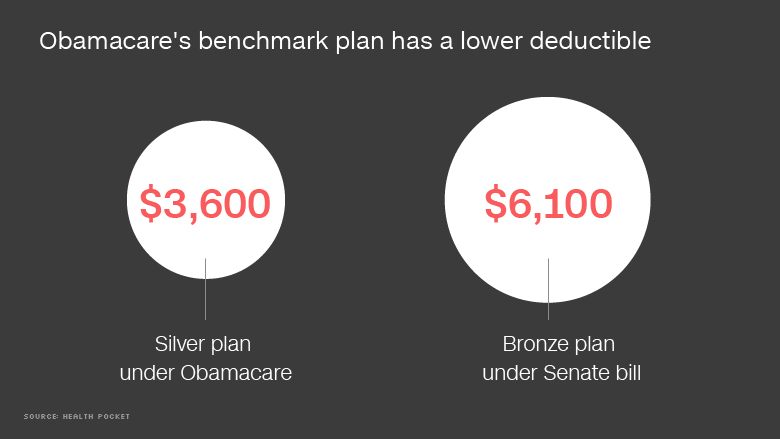

Not only will the premium subsidies be skimpier, so will the coverage. The Senate is tying these payments to less generous insurance plans, which have lower premiums but higher deductibles.

Under Obamacare, subsidy payments are based on the price of the second-lowest cost silver plan in one's area. Silver plans pick up about 70% of a consumers' cost for care, on average. In 2017, the average deductible for a silver plan was just under $3,600, according to Health Pocket, an insurance shopping site.

The Senate bill, however, would provide subsidies based on a plan that covers about 58% of consumers' costs, on average. This is slightly lower than Obamacare's bronze plans, which had an average deductible of nearly $6,100 in 2017. This means consumers will likely have to pay more out of pocket to see the doctor and get treatment, though it reduces how much the federal government has to spend on the subsidies. Or they will have to pay higher premiums to get a comprehensive policy.

"A really healthy person who doesn't use a lot of care but just wants the coverage in case of an emergency would benefit," said Christine Eibner, senior health care economist at Rand, a research and analysis firm. "Someone who is older or uses more care will have to pay more to get equivalent coverage under this bill."

Related: 22 million fewer Americans insured under Senate GOP bill

This change would mean that premiums for the average benchmark plan would be 20% lower by 2026, according to the Congressional Budget Office. But that's largely because the benchmark plan under the Senate bill would pay for a lot less. Also, the CBO notes, the change in premiums could vary greatly by state, depending on how many Obamacare regulations the state opts to waive.

Some folks, particularly those who don't have a lot of medical needs, are willing to make this trade off. Republicans argue this will bring more healthy people into the market, which will lower premiums more broadly.

"The Senate is trying to make the market more attractive," said Laszewski, who is critical of Obamacare.

Fewer Obamacare protections

The Senate bill would also make it easier for states to waive out of many Obamacare insurance regulations, which mandated what health benefits insurers must cover and limited how much of the financial burden they could place on policyholders.

This means that insurers could cover fewer services -- such as maternity, substance abuse or prescription drugs -- in states that opt for waivers. So policyholders would have to pay for these benefits on their own and could be subject to annual and lifetime limits on insurance coverage.

Related: Senate health care bill gives $250,000 gift to the mega-rich

But it also means that insurers would no longer be bound to limiting consumers' out-of-pocket costs in individual market policies -- in 2017, policyholders don't have to pay more than $7,150 a year for essential health benefits covered in their plans. So carriers could bring back so-called "catastrophic plans" that have deductibles of $10,000 or more for a single person.