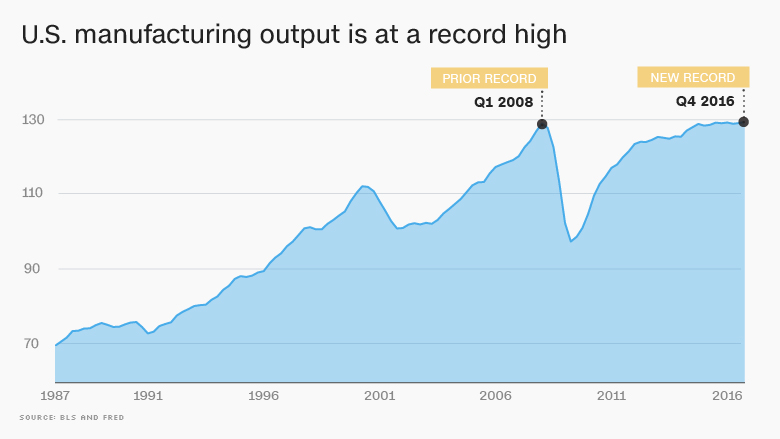

The United States is making more things than ever before.

Yes, you read that right. Manufacturing output is at an all-time high, according to one government statistic (others indicate it's near a record).

Evidence of the boom is visible when you drive around America's muscle town: Detroit. The giant Ford (F), GM (GM)and Chrysler (FCAU) factories are buzzing to try to keep up with record levels of U.S. car sales. Yet a deep sense of unease is palpable in Michigan.

A lot of people are nervous. They see that U.S manufacturing has roared back, but the jobs -- especially $30-an-hour jobs -- have not. There's a huge debate about why these jobs disappeared: Some blame robots and machines for replacing humans; others say the jobs went to Mexico, China and beyond.

"There's kind of this quiet depression that's going on," says Matt Seely, the CEO of Quality Bending and Threading, a small manufacturing shop in Detroit. "People are OK, they're getting by, but no one's really in their happy place."

Donald Trump promised Michigan good jobs. It's a key reason why he won Michigan by 10,704 votes, the first Republican to carry the state since President George H. W. Bush in 1988. Now his supporters expect him to deliver.

"This is a manufacturing state. Like all of the states in the Rust Belt, these people are hurting. They want to work," Seely told CNNMoney.

In his first major address to Congress this week, Trump proclaimed that "dying industries will come roaring back to life." It's exactly what Seely wanted to hear.

Related: NAFTA is 'killing the American Dream,' Michigan workers say

From 17 employees to 5

Seely and his wife voted for Trump. They even volunteered on his campaign, the first time they ever felt motivated enough by a politician to do that. Seely, who wears a suit with a red pocket square, is a big believer in Trump's "Buy American" movement. He thinks U.S. manufacturing can -- and should -- be even stronger than it is now.

His own shop is profitable these days, but not like it used to be. In the late 1990s and early 2000, he had 17 employees and "the phone was ringing" with orders for the specialty steel products his team makes.

Now he's down to just five employees, a few of whom are college students. One is studying to be a dentist. To him, this machine job is temporary, not a place to build a career.

America has lost 5 million manufacturing jobs since 2000. Nearly 300,000 of those losses occurred in Michigan.

'I didn't think it would get this bad'

Half an hour north of Seely's shop lies Sterling Heights, a big Detroit suburb where Jim and Peggy Stewart live. The Stewarts know what it's like to scrape by. They lost their jobs and then their home in the Great Recession. In their 50s at the time with four kids at home, they set aside their pride and relied on food banks for the first time in their lives.

"I didn't think it was going to get this bad. I really didn't," Jim told CNNMoney. After working for 17 years in glass manufacturing, he found himself unemployed and competing against teens to cut grass for $10 an hour.

The Stewarts credit their church -- and their marriage -- for their ability to survive that period. Today, both have jobs again -- Jim at Ford and Peggy at a corporate security firm -- although the pay is less than they want.

Peggy voted twice for President Obama, but she went for Trump in 2016, largely because of the economy.

"I'm behind Trump because he has a spine," says Peggy, now 62. She makes $9 an hour, barely above Michigan's minimum wage. She had a similar job before the crisis. It paid $11 an hour.

In August, Trump visited Michigan and asked voters, "What do you have to lose by trying something new, like Trump?"

Related: Even Trump voters want the minimum wage raised

In Michigan, many want Trump to go after NAFTA

Unlike his wife, Jim wasn't convinced a billionaire like Trump (or millionaire like Clinton) would do anything for working Americans like their family. He tried to write in "Screwy Squirrel," an old cartoon character, on his presidential ballot.

Politicians "are fairly clueless as to what an average person's life is like," says Jim, now 55. One of their sons is in the Air Force. He just got word he'll be in the Middle East by April.

But there's one thing Jim really applauds Trump on so far: Getting the U.S. out of the TPP trade deal in Asia. Jim thinks trade deals like NAFTA have caused manufacturing jobs to disappear and wages to go down. CNNMoney heard that from just about everyone we met during a week of interviews in Michigan.

We "need to renegotiate NAFTA. That was Clinton and we got the stinky end of the stick on that one," says Jim. He likes his job at Ford, but he'll never earn more than about $20 because he was hired into a plant that cut a deal with the union to pay new hires there far below the $30 norm.

NAFTA, the deal with Mexico and Canada that allows goods from those countries to come into the U.S. tax free, went into effect in January 1994. U.S. manufacturing actually did well for much of the 1990s. But it's been a different story since 2000, the tipping point when manufacturing jobs began to disappear rapidly.

As manufacturing jobs declined, other sectors grew. Unemployment in Michigan has been 5% or less for the past year. It's the lowest level since 2001. But workers say there's one big problem: A lot of the jobs around now don't pay well. The Stewarts certainly feel that way. So does Angelica West.

Related: Trump gives America's 'poorest white town' hope

I gave up on manufacturing

West grew up in a blue collar family in Lapeer, Michigan, a city about an hour from the U.S.-Canadian border. She admits she "got in the wrong crowd" in high school and never finished. She didn't worry about it at first. She just walked into a temp agency and landed a manufacturing job.

She worked at a GM parts plant and then on the assembly line of Lesley Elizabeth, a company that makes cooking oils and spices. She figured manufacturing would be her life.

But those jobs paid minimum wage -- barely above $8 an hour in her state.

"I was only bringing home $960 a month," the soft-spoken mom, now 28 and the mother of three young boys, told CNNMoney. "Daycare alone was almost $400 to enroll my kids in."

About a year ago, she moved back in with her mother and went back to school to get her GED through a state program. Her family also receives Medicaid to cover health care. She hopes to retrain to be a nurse.

West and her mother are Trump supporters. They see him as an "action president." They especially like what he's doing on trade and immigration.

"I'm not racist at all, but I do believe in building a border [wall] to protect our country," West says, referring to Trump's promise to construct a wall along the U.S.-Mexican border. "We can't even take care of our own people right now."

Related: Be 'very afraid' about globalization's next phase

Even union workers are worried

Last week Trump promised, yet again, that his economic plans "will return significant manufacturing jobs to our country." He's gone as far as to vow to create 25 million jobs, the most of any president.

The jobs Trump supporters envision when he makes statements like that are the $30-an-hour auto worker jobs. CNNMoney sat down with several Ford workers in Detroit. They feel they've lived the American Dream, but even they are worried about the economy.

"I want my kids to have a future. I want my kids to have jobs," says Sal Moceri, a 61-year-old Ford factory worker and UAW member. All of his union brothers in the room nod in agreement.

There were 103,000 American UAW workers employed by Ford in 1994, the year NAFTA took effect, according to a UAW spokesman. Now there are just 56,000.

"Trump offered to bring these auto jobs back," says Frank Pitcher, 49, who hosted the interview in a large middle class home with a big-screen TV. "For me, it meant that many other Americans were going to get that same opportunity."

Moceri and Pitcher both voted twice for Obama. But in 2016, they went for Trump.

"I've been a long Democrat," says Moceri. But he felt "people needed a change."

Michigan swing voters like Moceri and Peggy Stewart feel Trump is already delivering on his jobs promise. They like what they see when companies like Carrier say they'll keep jobs in the U.S. But Moceri, an immigrant from Italy, was livid at Trump's refugee ban. Peggy Stewart thinks Trump's trying to do too much too fast.

"I hope it's not the biggest mistake of my life," Peggy Stewart said of her Trump vote. "Some of us are working too hard to fall back now."

To contact the author of this story, email heather.long@cnn.com.

-- CNNMoney's Richa Naik and Logan Whiteside contributed to this story.