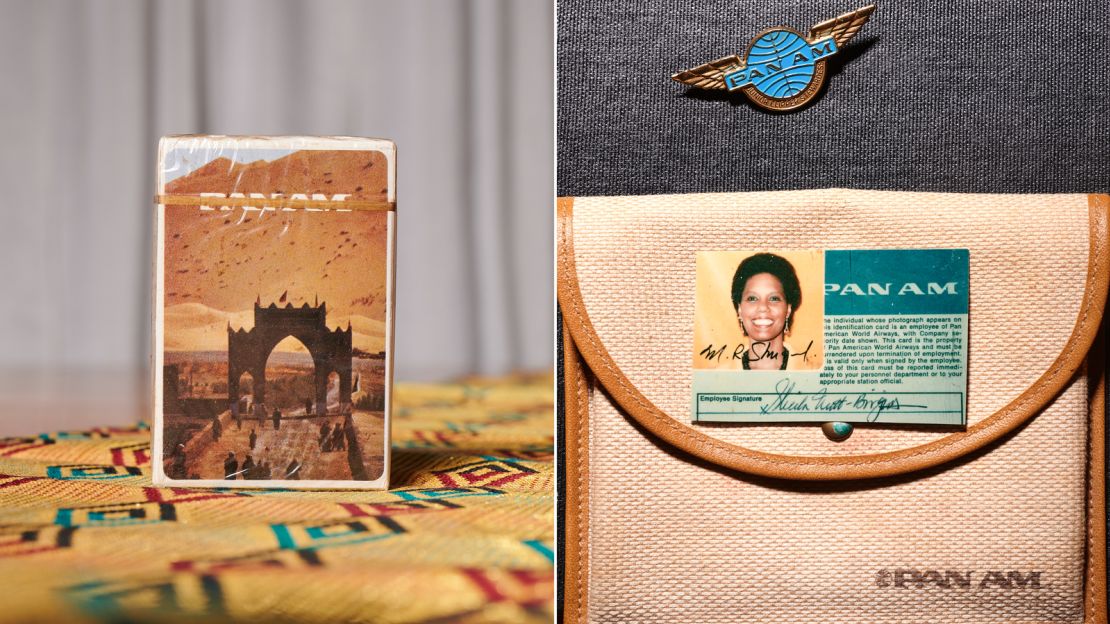

In the summer of 1969, Sheila Nutt was one of just two Black women in a crowded Philadelphia hotel, waiting to interview for a coveted role as a flight attendant for Pan American World Airways.

Nutt was a 20-year-old college student living in Philadelphia. A couple of years previously, she was first runner-up in the Philadelphia division of the Miss America pageant.

“I was the first African American to be selected as the first runner-up,” Nutt tells CNN Travel today. “Although I was not selected as the winner, I was very excited about the outcome anyway.

“I kind of felt like a trailblazer.”

In between rounds, Nutt chatted with the other pageant contestants about her life goals, voicing her dreams of becoming a model or an actress. One of the women mentioned the airlines were looking for flight attendants – the advent of the jet engine had opened up international travel and airlines were booming.

Nutt was intrigued by the idea of working as a flight attendant. It was a ticket out of Philadelphia and to her future.

“There was a possibility that if I became a stewardess, I could be discovered on an airplane,” says Nutt.

After the pageant ended, Nutt recalls eagerly flipping through the local Sunday newspaper with her best friend Sandy. They turned to the job listing page and spotted an ad posted by Pan Am.

The role wasn’t open to everyone. Applicants had to have a college education, speak a second language and be a certain height and weight, and eye glasses were banned. But the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbade discrimination against applicants based on race, so applicants from all backgrounds were encouraged. The first wave of Black flight attendants had started flying a few years previously, and Nutt and Sandy were keen to join them.

As she sat waiting to be interviewed, Nutt flicked through the Pan Am brochures laid out on the coffee table in front of her. Bright images of Rome, Paris, Istanbul and Buenos Aires were splashed across the pages.

“I’d only read about those places in history books,” says Nutt.

The thought of visiting these destinations was thrilling.

“Oh my gosh, I really want this job,” Nutt recalls thinking.

No longer did Nutt see working as a flight attendant as a means to fulfill a larger dream of acting or modeling – flying sounded like a dream job in itself.

“Traditionally, African Americans were not traveling the world, we were going from Philadelphia to Atlanta,” she says. “So the whole idea of seeing the world was exciting for me.”

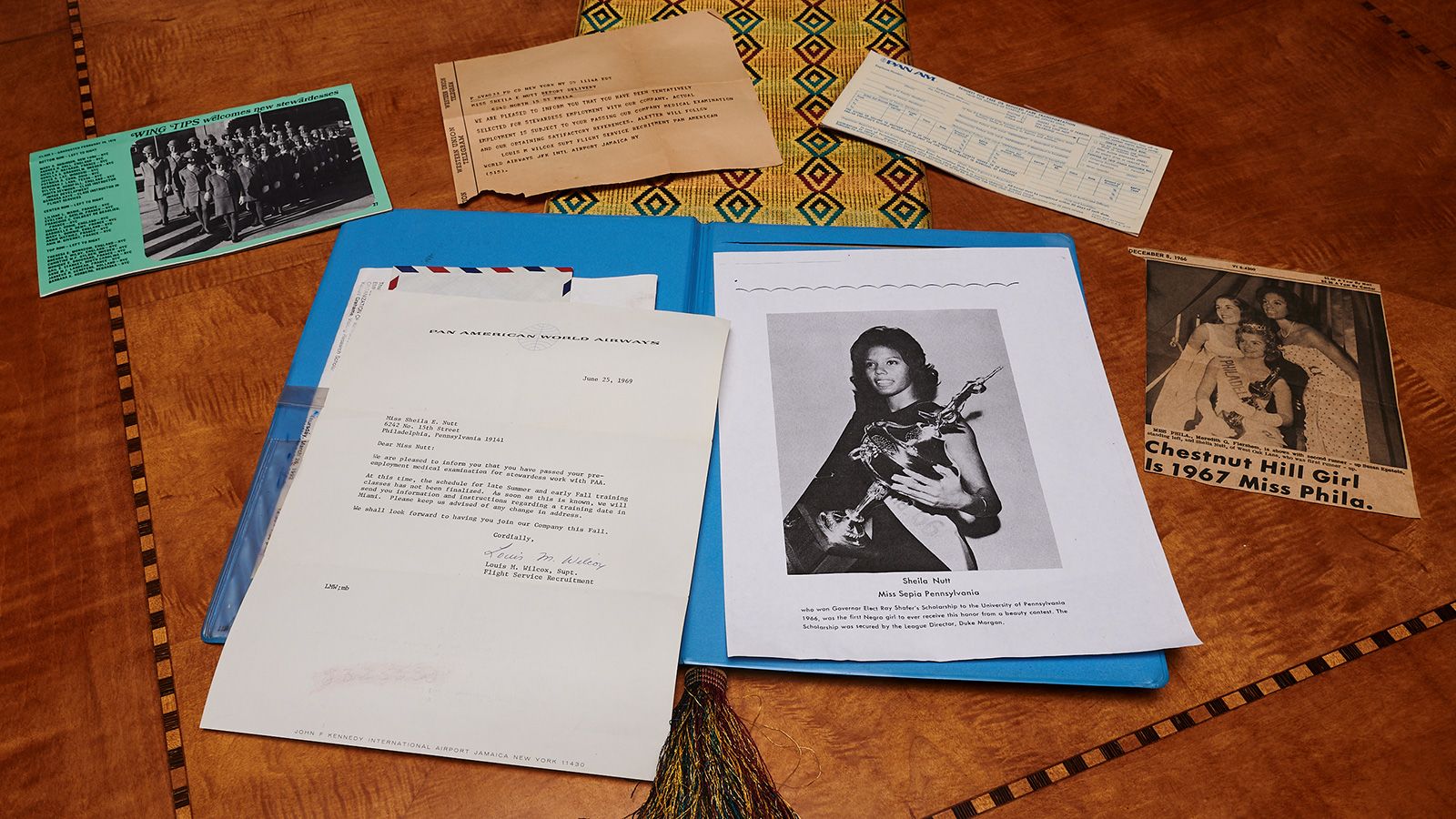

Photos: Traveling the world as one of the first Black Pan Am flight attendants

The interview went well. Nutt says she wasn’t thrown when the interviewer asked her to demonstrate her “walk.”

“I’d been in beauty pageants, I knew about walking across the room in a way that showed a level of grace and confidence,” says Nutt.

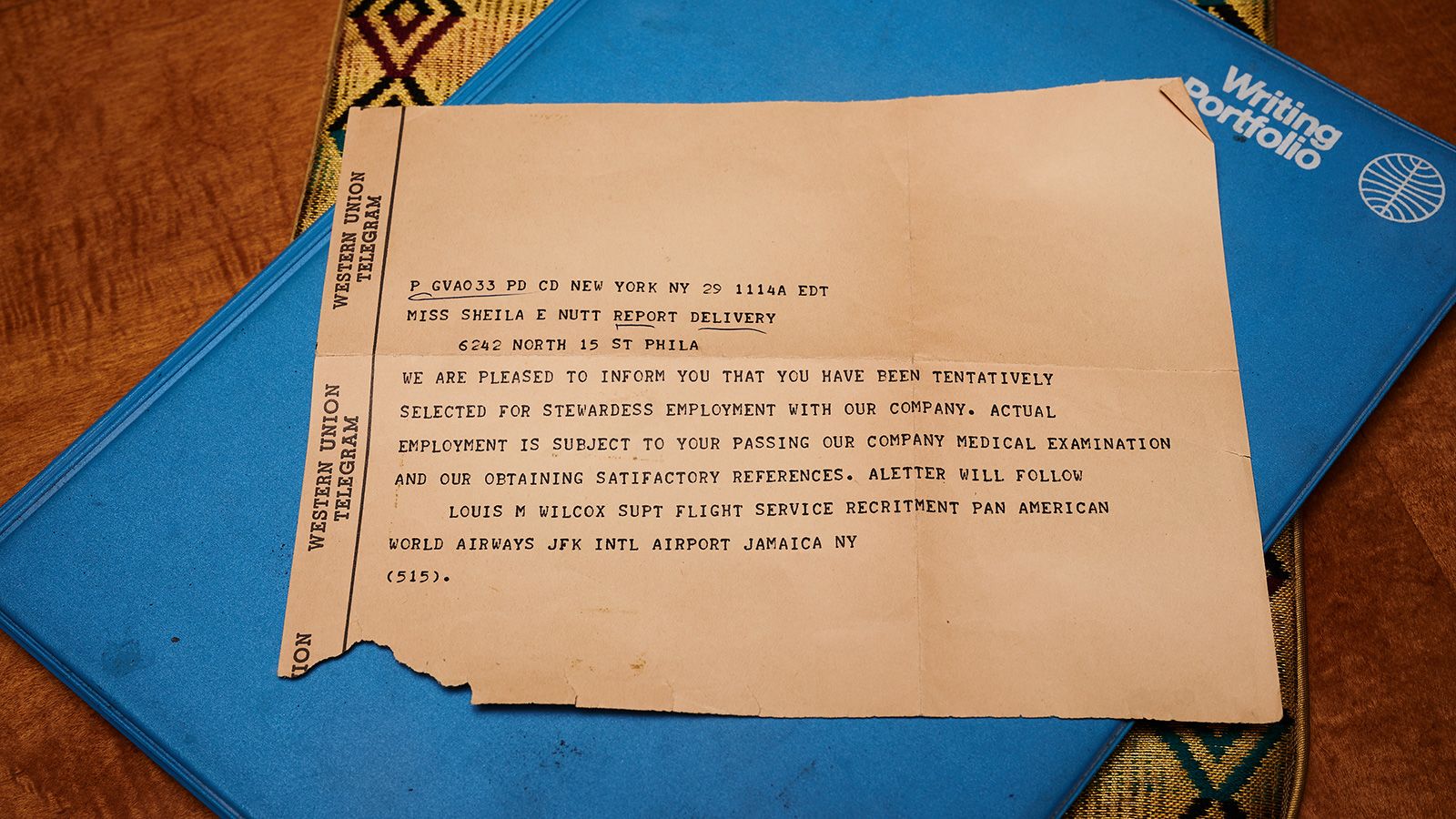

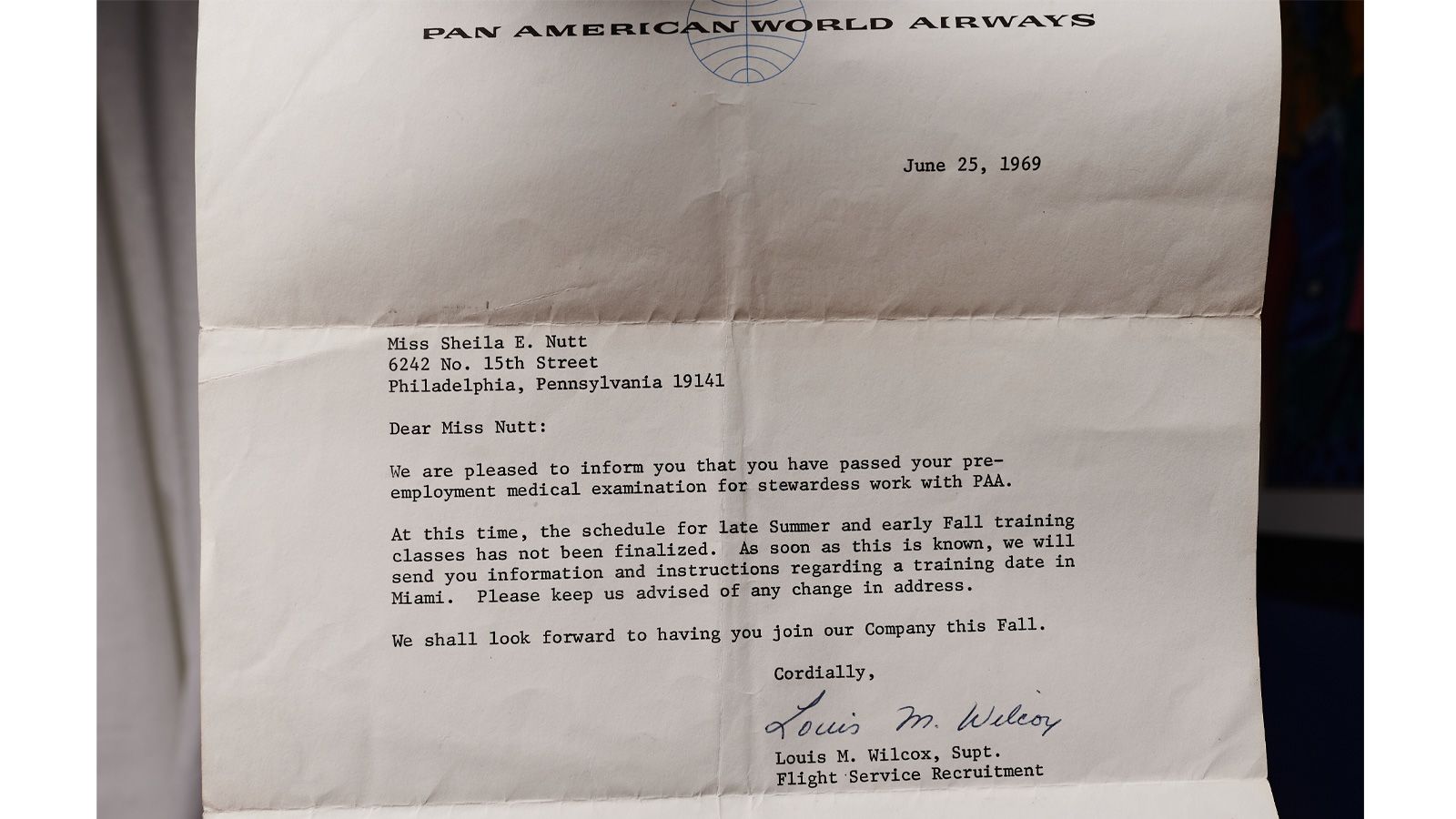

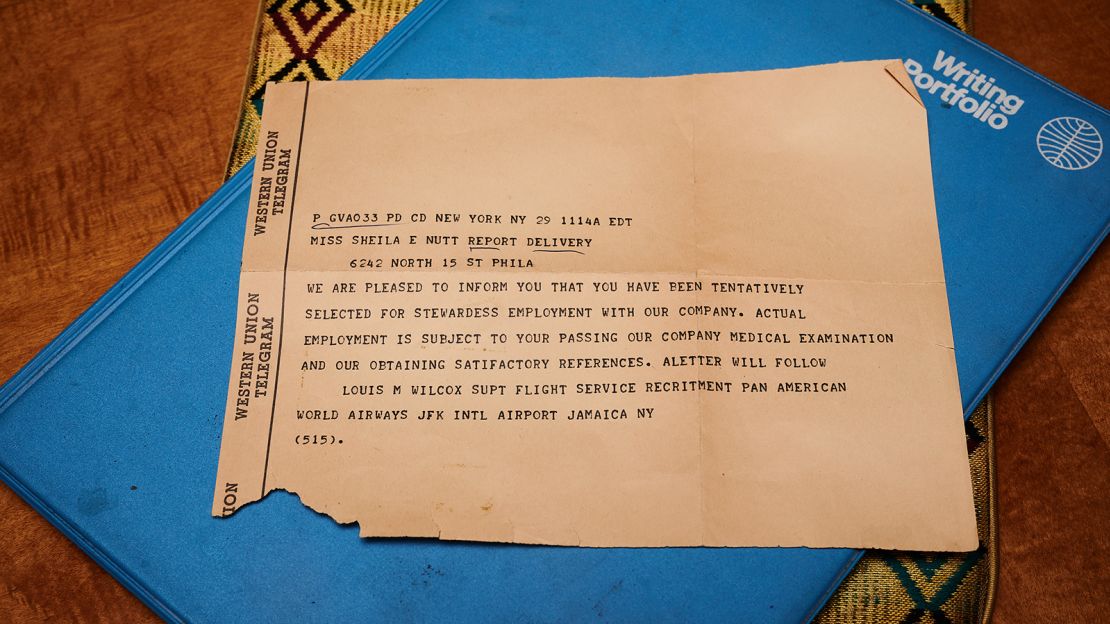

Two weeks later, Nutt received a telegram informing her she was in. All that was left was to pass a medical exam and to head to Pan Am training school.

“When I got the telegram, I ran upstairs to my bedroom, I opened it, and I screamed and hollered, and I said, ‘Oh, my goodness!’ and my mother thought that something bad had happened.”

Nutt recalls her parents initially voicing some concerns about her accepting the job.

“They grew to appreciate and understand my desire to get out of Philadelphia and to see the world. I wanted to see those places that I had read about. I wanted to use the language that I had studied for four years in high school,” says Nutt.

Nutt’s friend Sandy wasn’t hired by Pan Am, but ended up working at United. The two women stayed friends, and were soon swapping stories of their adventures.

A new chapter

After her final semester of college, Nutt traveled to Miami for training in January 1970. She doesn’t recall any pre-training nerves.

“At 21, you have no fear,” Nutt says. “It was just excitement.”

Due to the Pan Am domestic flight schedule in 1970, Nutt had to travel from Philadelphia to Miami via Puerto Rico. The long journey was her first taste of what the next chapter of her life would look like.

“On that flight from Philadelphia to Puerto Rico, I informed the stewardesses on Pan Am that I was going to training school and they were just fabulous. They were so kind and they were so encouraging and telling me all the great things that I would be experiencing.”

Nutt flew to Miami First Class on a Boeing 707. Back then, flight attendants would cook food for passengers mid-air. Sitting in the in-flight lounge, Nutt overheard one of the crew members discussing how tired she was of eating steak on the job.

Nutt remembers listening in disbelief. How could anyone tire of eating steak?

“My eyes were opened, ” she says. “And I was just very excited – I guess that’s the operative word, excitement – and eager to find out what the world had to offer me.”

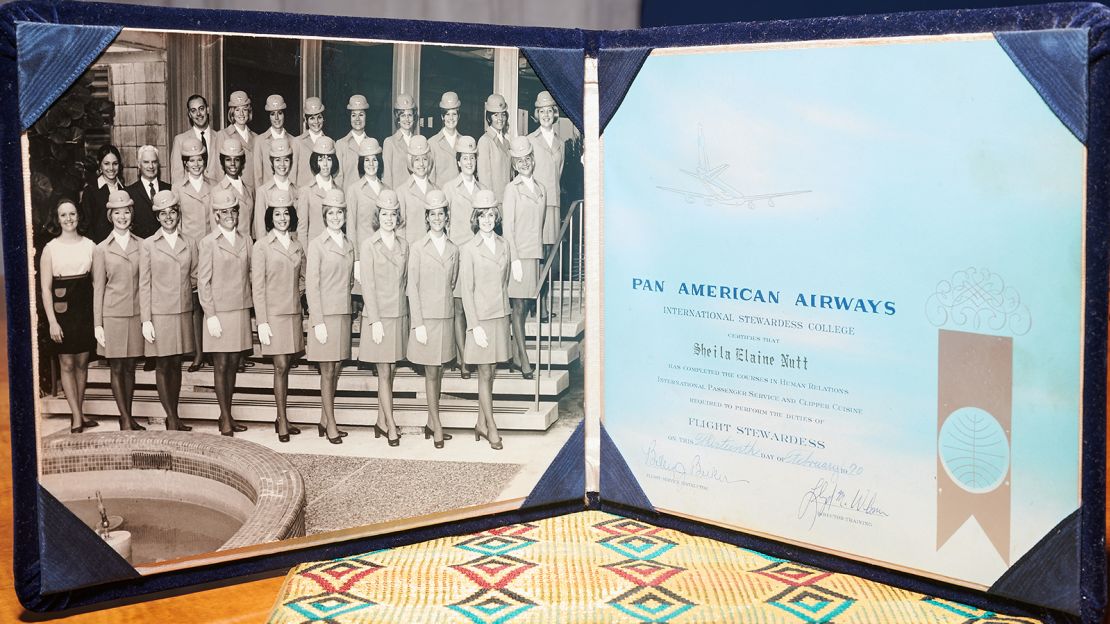

The Miami-based training lasted a month. Nutt was the only Black woman in the class.

Growing up, Nutt had frequently found herself in spaces in which she was the only person of color.

“I developed the ability to code-switch, the ability to embrace diversity, equity and inclusion and justice early on in life,” she explains. “I learned how to accommodate and overcome the prejudices and racism and bullying and disrespectful behavior that some people tried to impress upon me.”

Nutt grew close to many of her classmates, some of whom she remains in touch with today.

“Over 50 years later, we communicate, we share our stories,” says Nutt. “I’m very happy to have encountered these women. It was a very valuable learning experience for all of us, because many of my classmates had never seen an African American in person.”

Nutt says the majority of trainees were “open and receptive and willing to incorporate diversity into their own personal and professional sphere of influence.” She did come face to face with some prejudice, and recalls one trainee who was more difficult, and who subsequently didn’t pass their probation.

“I did not allow their problems to have any impact on my ability to be successful, my ability to find happiness and joy, and fulfill my own purpose,” says Nutt.

Nutt describes the training curriculum as “very intensive.” The new recruits learned about “food, language, grooming, wines – we became connoisseurs of which wines were from what area, which wines went with particular menus.”

But training wasn’t only about learning to make travelers comfortable.

“Our main focus was the safety of our passengers,” explains Nutt. “So we had very intensive safety training – we had to, of course, pass examinations, take tests.”

Flying in the 1970s

Nutt graduated from Pan Am training as valedictorian of her class, and started flying out of Miami.

“I was among the first to fly on the Boeing 747, so that was my favorite airplane – perhaps you know that it held more than 400 people at a time. And it was in the vanguard of aviation history back in the 1970s,” says Nutt.

“The 747 would go to Italy, to Rome, which I really enjoyed because I loved the history of Rome. I loved being a tourist there, I loved eating the food and shopping in Rome.”

Nutt also enjoyed traveling to Nairobi, the Kenyan capital, and staying in the InterContinental Hotel. InterContinental was owned by Pan Am, so flight attendants were usually put up in the glamorous hotels during layovers.

On board, Nutt, who after six months working for Pan Am became a purser, and later a stewardess manager, cooked fine food for passengers that was served on china plates.

“In the First Class, we cooked everything from scratch,” she says, recalling meticulously perfecting roast beef to passengers’ likings.

Nutt enjoyed talking to travelers and says she was proud to be a Black ambassador for Pan Am, and for the US more broadly.

“We were the de facto ambassadors of America at that time. When people got on the airplane, that’s what they saw.”

Nutt and her fellow Black flight attendants would sometimes face discrimination from White passengers. Nutt recalls one particular interaction with a White passenger from South Africa, which at the time was racially segregated under apartheid.

“This particular passenger was disrespectful to me, and so I ignored him and continued to do my job,” she says.

Nutt says other travelers were “flabbergasted” by this man’s behavior.

“He went back to the galley and told the other stewardesses, or flight attendants, that he wanted to apologize, but he did not have the capacity to come and apologize to me. But I understood where he was coming from, I knew that he had issues that were not my issues.”

Nutt also recalls that Black Pan Am flight attendants were given special dispensation to fly to South Africa, granted honorary “White status.”

“It was very emotional. It was a very eye-opening and educational experience to have a chance to go into South Africa during apartheid,” says Nutt.

Creating a community

In rest periods in-air, Nutt and her fellow flight attendants would talk about their jobs and lives.

She describes her relationship with other Black Pan Am flight attendants as a “special camaraderie.”

“We shared stories, experiences and encouragement,” says Nutt.

Pan Am’s height and weight restrictions weren’t limited to recruitment – flight attendants were required to maintain a certain look and were sometimes subject to random weight checks. Nutt says such requirements were tolerated by Pan Am crew because of the travel opportunities the job afforded them.

“We knew the restrictions, and we were willing to put up with the restrictions, because we felt it was worth it,” she says.

“We were willing to play along. I think we were willing participants.”

Put me on record, it was a fabulous life. I enjoyed it. And when I did not enjoy it anymore, I left.”

Sharing a legacy

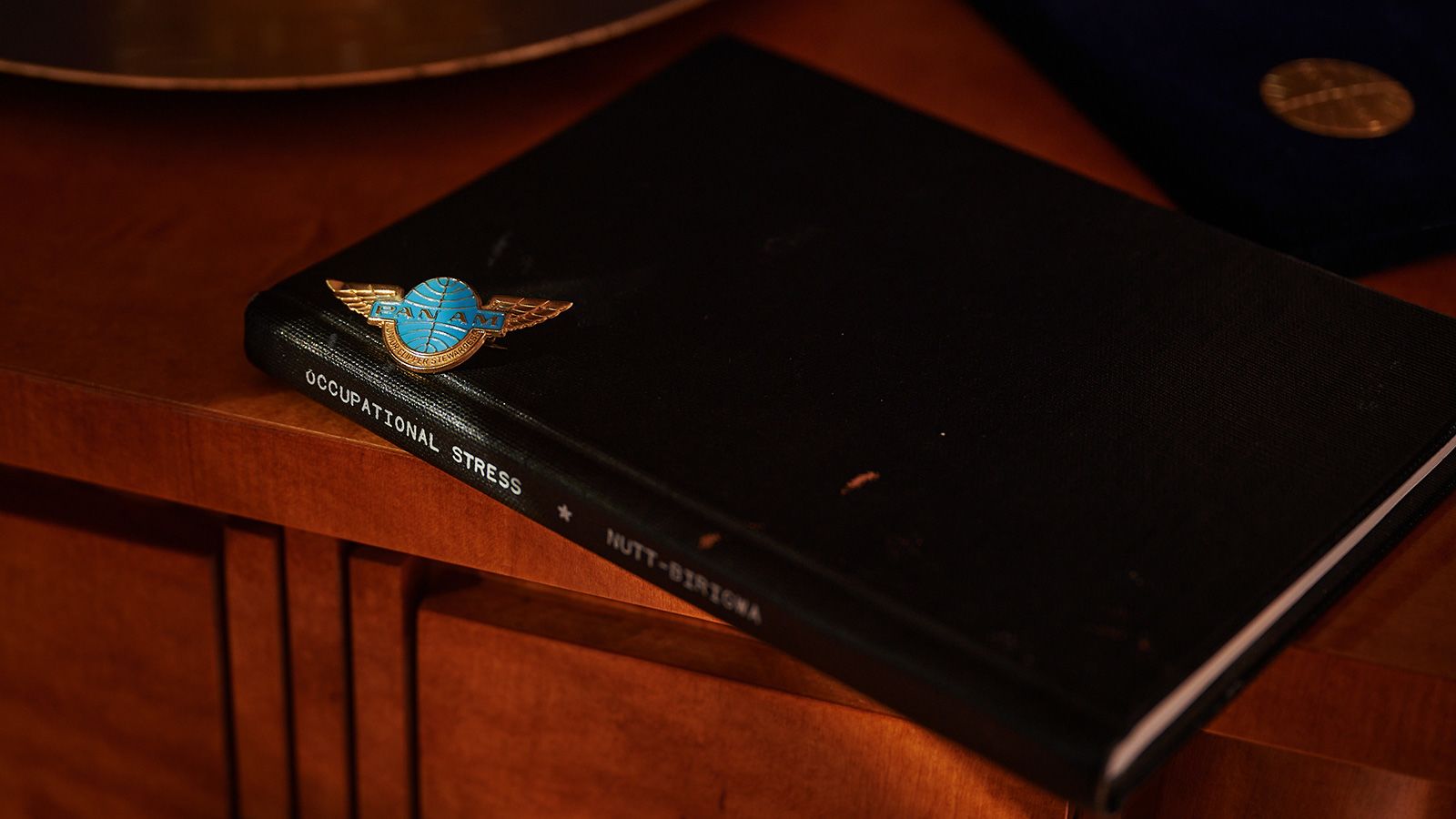

Nutt moved on from Pan Am in the 1980s. Before leaving, she enrolled on a Pan Am program that allowed flight attendants to study during the week and fly on the weekends. She received a doctorate from Boston University, writing a dissertation on flight attendants and occupational stress, and later studied for a Master’s degree in theological studies from Harvard Divinity School.

When Nutt left flying, she started working in education, and most recently served for fourteen years as the Director of Educational Outreach Programs at Harvard Medical School’s Office for Diversity Inclusion and Community Partnership, before retiring in 2020.

Nutt has been married for nearly four decades to her husband, who is from Ethopia. The couple lived in Addis Ababa for ten years.

“I loved being a stewardess, I learned so much about the world and myself traveling to foreign countries,” says Nutt, reflecting on her career today. “My respect for and appreciation of different cultures has contributed to the success of my marriage.”

Nutt says she also sees the impact of her years exploring the world on her children.

“They are bicultural and love to travel the world,” she says.

Nutt also still loves to travel, but says she’s in the happy position of not having anywhere left on her bucket list. When she left Pan Am, the one destination Nutt still hoped to visit was China, which was closed to international visitors through much of her tenure in the air. Nutt fulfilled that dream when she had the opportunity to travel to Beijing with Harvard.

When Nutt does fly today, she marvels at how different the traveling experience is, and how the role of a flight attendant has developed.

“Back in the day, there was the image of glamor – that played a major role in air transportation back in the ’60s and ‘70s and before,” she says. “Nowadays, it appears that it’s basically to get you from point A to point B, and be able to handle an emergency.”

On board service, notes Nutt, is also markedly changed.

“It’s just very different, and we’re talking a long time ago, times change,” she says.

Today, Nutt’s focus is on collating and sharing the stories of her fellow Black Pan Am flight attendants, who call themselves the “Pan Am Blackbirds.”

“These stories of African American men and women are an integral part of the overall aviation history, but the American aviation history, in particular,” says Nutt.

Nutt is currently putting together a podcast, called “Pan Am Blackbirds” that will shine a light on these stories. She hopes to create a lasting legacy.

“It’s the opportunity to hear our stories, in our words,” she says.

“I felt it was important for our stories to be saved, to be highlighted, to be respected and acknowledged.”

Top photograph of Sheila Nutt by Philip Keith for CNN