Lisbon has established itself as Europe’s hippest city-trip destination over the past couple of years, but now it has a rival that’s a little too close for comfort.

Portugal’s second-city, Porto, is giving the capital a run for its money as the place to go for a unique blend of history, balmy weather, culture, cooking and nightlife.

With its old riverside center designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, its chefs picking up a growing constellation of Michelin stars, as well as its world-beating wines and vast stretches of sandy shore on its doorstep, Porto certainty has a lot to offer, but can it really challenge Lisbon as Europe’s capital of cool?

We’ve put the two leading cities of Portugal head-to-head to find who has the best beaches, the tastiest snacks, the most opulent old cafés and trendiest boutiques.

And because we like to give the underdog a hand, we’ve asked some hardcore tripe-eaters (as the inhabitants of Porto are known – see below) to tell us why you should all be heading to their city by the sea.

They tend to hold strong opinions.

Take Rui Reininho, Portuguese rock superstar and front man with the legendary Porto band GNR.

“The baroque surprises, the escarpments of Romanesque granite, the almost obscene sincerity of the people, the impetuously golden river, the swooning camellias, the wild Atlantic filled with fish and seafood, the narrow streets awash with soap suds,” Reininho enthuses. “You really shouldn’t hesitate between Lisbon’s tropical style and the Celtic, European liberalism of Porto.”

READ: Lisbon might be Europe’s coolest city; here are 7 reasons why

Tripe eaters v. little lettuces

The people of Porto are affectionately known as tripeiros – roughly tripe-eaters.

The nickname comes from the city’s signature dish, tripas à moda do Porto: a mess of white beans fortified with pig’s ear, calves’ foot, cow’s stomach (aka tripe) and a cartload of other chewy bits.

Legend has it that Porto got its taste for offal in 1415, when the city’s patriotic inhabitants handed over all their meat to a Portuguese army off to war in Morocco, leaving themselves with just the offcuts.

Lisbonites, on the other hand, are called alfacinhas – little lettuces – supposedly after the cries of hawkers selling freshly cut vegetables from market gardens that surrounded the capital.

Tripeiros will say that the food habits reflect the cities’ contrasting styles: Porto is solid, no-nonsense, hardworking; Lisbon, laid-back, decadent and vain.

“It’s the people that makes Porto special,” says Sara Figueiredo, selling designer jewelry and locally crafted soaps in the gift shop of Porto’s uber-trendy Serralves arts center. “There’s all that history, but above all it’s the people here, they are so welcoming.”

Figueiredo knows her tripe – her tip for a hearty helping is the Adega do Olho, a backstreet dive devoted to old-school Porto cooking, where a plate-load of tripas will set you back 3.50 euros ($4). (6, R. Afonso Martins Alho, 4000 Porto; +351 22 205 7745)

MORE: A food guide to Europe’s best-kept culinary secret

Douro v. Tagus

Both cities sit on mighty rivers rushing towards the Atlantic Ocean after flowing west from sources in distant Spanish highlands.

Lisbon’s Tagus spreads out before the city, forming one of Europe’s largest estuaries: a shimmering surface some 15 kilometers wide at its broadest point. It’s crisscrossed by little orange commuter ferries, has colonies of flamingos grazing on the far bank and reflects the sun’s rays to give the capital its milky white light.

Porto wraps the Douro in a cozier embrace.

The city rises up on steep hills on both banks (although Vila Nova de Gaia, the historic south-side wine center, is technically a separate city). Its old neighborhoods cling to the slopes and look down on a flotilla of barcos rabelos – high-prowed longboats that once carried kegs of wine down from upriver vineyards and now bob decoratively in the stream.

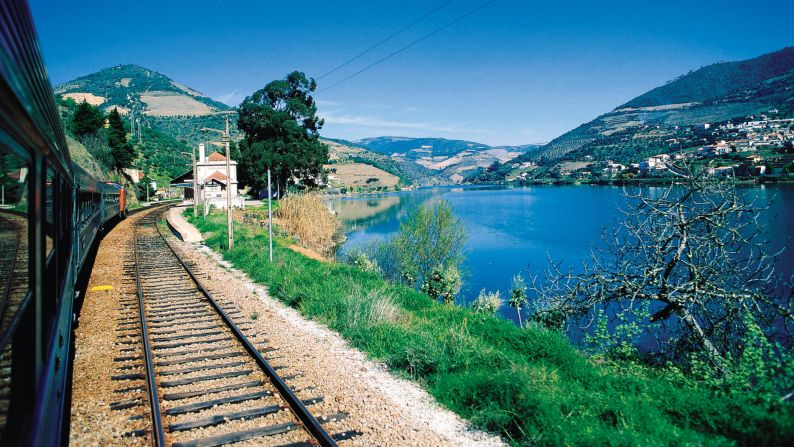

Liquid gold: Portugal's stunning Douro river region

Douro means “river of gold” and the dying rays of sunset give the waters a gilded glow. Among the five bridges spanning the Douro in Porto, the oldest, Ponte Maria Pia, is a curving iron arc built in 1877 by Gustave Eiffel, the tower guy.

“I love the bridges, especially Ponte Dom Luís I, which has two levels, one down below, the other way up above,” says Ganna Bocharova, who moved to Porto 15 years ago and is part of Porto’s Ukrainian community, the second-largest immigrant group after Brazilians.

“I really like it here,” says Bocharova, out shopping with her family. “Porto is small and compact, you can walk or bike everywhere. The food is good, people are friendly. I’m here to stay.”

MORE: The world’s tastiest rail journey

Ribeira v. Alfama

The historic cores of both cities comprise a plurality of medieval neighborhoods complete with winding alleys, flaking ochre facades and little squares overlooked by ancient churches.

In Lisbon, the best known is Alfama, spiritual home of Portugal’s plaintive fado music, tumbling down to the Tagus. Porto’s is Ribeira, clinging to the steep north bank of the Douro.

They share much in common, but are immediately distinguished by the raw material of their construction.

In Alfama, as in most of Lisbon, soft white limestone dominates. Old Porto is made of more somber gray granite. In paintwork, Alfama has lighter, more pastel shades, Ribeira prefers darker hues, and tiled facades. Ribeira is more tightly packed, more intimate, perhaps even a bit claustrophobic, but Ribeira – for the moment – has an advantage.

Years of tourism success have changed Alfama: These days you’re more likely to hear the chatter of French tour groups than fado echoing down its lanes.

The last traditional grocery store closed in 2016. Souvenir stores and bars are mushrooming. Vacation rentals are pushing out the locals who gave the district its color.

Similar changes are coming to Ribeira, but it retains more of its edgy authenticity.

“Ribeira has those old taverns, a culture of tradition, that’s characteristic of an old people. It’s got good restaurants and then there’s the river, the most beautiful part of our River Douro,” says Maria Olinda Ramisio, a stalwart stallholder in another icon of old Porto, the Bolhão market, which has been providing the city with vitals since 1950.

Ramisio’s sells tripe, blood sausage and other offaly treats like chouriço sausage made from pork marinated in port wine. Naturally, she has opinions on where to eat well in Ribeira, recommending the riverside Filha da Mãe Preta and D. Tonho restaurants.

Filha da Mãe Preta, Cais da Ribeira 39, 4050 Porto; +351 22 205 5515

D. Tonho, Cais da Ribeira 13-15, 4050-509 Porto; +351 22 200 4307

MORE: Here are some bookstores around the world you don’t want to miss

Battle of the beaches

Both Porto and Lisbon are blessed with their proximity to miles and miles of Atlantic-splashed sand.

The capital’s beach life starts at the mouth of the Tagus, stretches around the tony resort of Cascais, up to the blustery coves of mainland Europe’s most westerly point near Sintra and the surfer hideouts further north. Across the river is the 20-kilometer (12-mile) curve of soft sand of Costa da Caparica and the golden crescents of soft sand cut in to the Arrábida hills.

Porto’s beaches are even closer.

The resort of Foz sits within the city limits, where the Douro meets the ocean. Its strips of sand interspersed with rocky outcrops running north beyond the promenade are among Portugal’s best urban beaches.

Foz also contains some of Porto’s poshest real estate, plus a collection of hip boutiques, cool bars and trendy restaurants.

“Foz is an area that not so many tourists come to, they tend to stay in the center, but it’s beautiful here. We’ve got the river, the sea, the beaches, great shops and restaurants. They should come out here,” says Marta Marques, who designs children’s fashion for the Foz-based Piupiuchick brand.

For a bite, she recommends the Casa Vasco: “It’s a small place, that’s always full all through the day, at lunch time, or after work, when people drop by for a drink. It’s relaxed, the terrace is always packed.”

South of the Douro is the broad sandy shore of Espinho, further north is an almost unbroken string of beaches for every taste running up to the Spanish border, barely an hour away.

“Being primarily seen as a city break, many don’t make the short hope down to the fabulous beaches we have,” says Chef Ricardo Costa, whose restaurant in the fabulous The Yeatman hotel perched above Douro earned its second Michelin star this year (The Yeatman, Rua do Choupelo, 4400-088 Vila Nova de Gaia; +351 22 013 3100).

“On the south side of the Douro River there is 15 kilometers (almost 10 miles) of blue-flag beaches which are long and sandy and maintained in excellent condition. Lined by wooden walkways and cafés and restaurants, it’s the perfect place to pass a lazy afternoon in the summer.”

Of course, Costa also has an interest in what lies beneath those Atlantic waters.

“The fish market in Matosinhos is also a great experience,” he says. “You need to get up early, it starts at about 5 a.m., but if you’re a foodie it’s a morning well spent.”

Late risers can always sample Matosinhos’ seafood over lunch, the ocean-front suburb is packed with superlative marisqueiras (seafood restaurants.)

Who owns the night ?

“The nightlife is amazing here. There are new places opening all the time, a bar on every corner. The atmosphere is really special.”

So says Teresa Campos, student of nutrition at the University of Porto, as she takes a break from entertaining passersby as part of her tuna. Tunas are bands of student troubadours, clad in traditional black university capes who wander Portuguese cities playing guitars and singing folk tunes.

Campos and comrades of her all-girl troupe recommend the happening bars around Praça dos Leões and the ultra-hip Galerias de Paris area.

There are plenty of fancy new places for drinking and dancing the night away, but their favorite is Café Piolho, opened in 1909 and a hangout for generations of students. It served as a dissident meeting place during Portugal’s long dictatorship. “Everybody goes there,” says Campos. It’s open from 7 a.m. to 4 a.m. (Café Piolho, Praça de Parada Leitão 45, 4050-011 Porto, +351 22 200 3749).

Of course, Lisbon is not exactly the sort of place where the young people are tucked up in front of the TV with a cup of cocoa at 10 p.m. The party scene in bar-backed neighborhoods like Bairro Alto and Cais do Sodré, and riverside clubs like Luz and Urban Beach are magnets for night owls from around Europe.

READ: 20 of Europe’s most beautiful hotels – from Ireland to Greece

Port v. Ginjinha

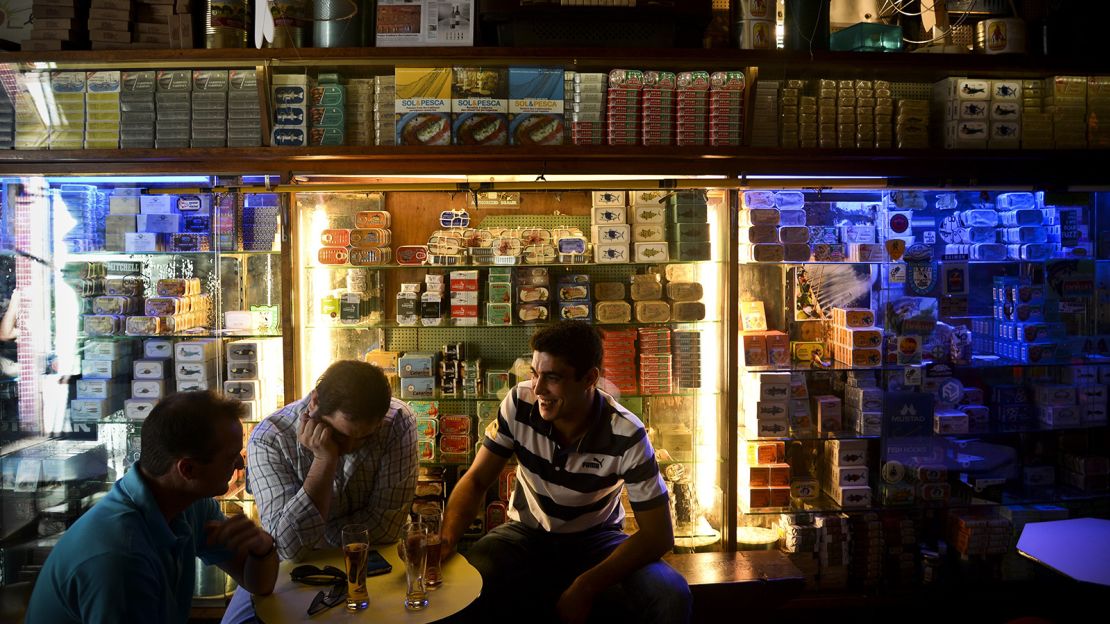

In battle of the beverages, Porto has a clear edge.

Lisbon’s most typical tipple is ginjinha, a sweet, cherry-based liqueur sold in shots from venerable hole-in-the-wall joints around Rossio Square.

Porto’s gift to the booze world is altogether more noble.

Port, which takes its name from the city, has been revered as one of the great wines for centuries, beloved by English lords, Russian tsars and connoisseurs the world over.

It’s made from grapes grown up on the Douro wine region, a magnificent, UNESCO World Heritage site, made up of terraced slopes rising up from the meandering river, that starts about an hour upstream from Porto.

Basic wines are shipped down to the historic wine lodges in Gaia on the south bank where they are blended with brandy and left to ripen in bottles and barrels until they they reach their full grandeur.

“The whole port wine culture is completely unique. It’s something really special. You’ve got all those wine lodges across the river that are centuries old, where the wine is left to mature,” says João Brás, owner of Castelo Santa Catarina, Porto’s quirkiest hotel, housed in a towering mock-medieval folly build in 1887 as a textile tycoon’s mansion.

“Visitors should definitely visit the wine cellars, they all offer tours and tastings. There are basic tasting with the regular wines, but they should pay a bit more to sample the vintages.”

Castelo Santa Catarina, Rua de Santa Catarina 1347, 4000-457 Porto; +351 22 509 5599

The best view

Neither Porto nor Lisbon are easy on the calf muscles.

Both were built on hills rising up sharply from their rivers. Visitors are rewarded for their aching legs by the sweeping views over the cityscapes from the upper reaches of those hills.

In Lisbon, there are countless viewpoints, or miradouros. From Portas do Sol square you overlook the tiled rooftops of Alfama winding down to the Tagus. The whole of downtown is spread out below the terrace in front of the Graça church, or its counterpart on the opposite hill, São Pedro de Alcântara.

Many people’s favorite view of Porto is from the miradouro fronting Nossa Senhora do Pilar, a round church, high on a cliff on the south bank on the Douro reached by the upper deck of Dom LuÍs I bridge. The view over the river, the colorful houses of Ribeira and the city rising up beyond is impressive at anytime; at sunset, it’s unforgettable.

Climbing the 76-meter (250-foot) baroque tower of the Clérigos Church is another way to get a great view of Porto, but author Richard Zimler, a New York-born tripeiro, prefers a more discreet view.

“There is a miradouro, at the end of the rua São Bento da Vitoria in the center of what was once the old Jewish quarter,” says Zimler, who has lived 27 years in his adopted city.

“It’s a very old street and when you get to the end, there’s a lookout with the most gorgeous, gorgeous, special view of the old townhouses of Porto tumbling down to the riverside. From that one vantage point you can see the river, the wine houses, the barcos rabelos, and if you look to the left, you can see the cathedral and the upper town of Porto.

“It’s a view that takes everybody’s breath away. And the thing that is amazing about it, and that only could exist in Porto, is that nobody has fixed it up, it’s a mess. The building next to is completely falling apart. It’s not paved, there’s garbage in certain place. That sounds awful, but it’s very Porto,” he says.

“You still find these secret places that are absolutely extraordinarily beautiful that no one has bothered prettying up.”

MORE: 6 resorts and hotels where the kids don’t come

Café society

Splendid old cafés form an essential part of the urban fabric of Lisbon and Porto.

Lisbon’s Confeitaria Nacional (Praça da Figueira 18B, 1100-241 Lisboa; +351 21 342 4470) has been serving up homemade pastries since 1829. A Brasileira (R. Garrett 120, 1200 Lisboa; +351 21 346 9541), is a literary landmark in the chic Chiado shopping zone, the mirror-lined, chandelier-lit Versailles ( Av. da República 15-A 1050-185 Lisboa; +351 21 354 6340) is constantly packed with Lisbonites washing down cream-filled delights with a shot of espresso.

Porto boasts the art deco delights of the Café Guarany (Av. dos Aliados 85/89, 4000-066 Porto; +351 22 332 1272) on its main drag, the imposing Avenida dos Aliados; and the 1950s vintage Café Ceuta (R. de Ceuta 20, 4050 Porto; +351 22 200 9376), but for José Xavier, a member of the little fishing community operating in small boats out of the mouth of the Douro, there’s one place that really stands out.

“The Majestic is a fantastic place, there’s no other café like it anywhere, everybody has to go there,” he say while hawking his catch from a riverside shed. “It’s the same with the Livraria Lello [perhaps the world’s most beautiful bookshop], there’s nothing like that either.” (The Majestic, Rua Santa Catarina 112, 4000-442 Porto; +351 22 200 3887)

Opened in 1921, the Majestic is a classic Belle Epoque-style coffee house, that remains a must for anybody passing through Porto. Worth trying are the rabanadas, Porto’s take on French toast: bread soaked in a rich egg custard, with cinnamon, lemon zest, nuts and sultanas.

Local legend has it Harry Potter was born here – the Majestic was a favorite of writer J.K. Rowling, when she worked as a teacher in Porto and began jotting down her first boy wizard story.

READ: 25 of the world’s brightest, most colorful places

Xavier does have one other tip: “Oh, and they should also go to McDonald’s, the one near City Hall, they should really check that out.”

Before it was taken over by the fast-food chain, 126 Praça da Liberdade housed the imposing Café Imperial and enough of its 1930s decor remains for this to be just about the grandest Big Mac joint anywhere.

Paul Ames is a freelance journalist based in Lisbon. He’s been hooked on Portugal since visiting as a kid in the 1970s.