Ever dreamed of opening an artisan boutique and settling down for good in an idyllic village in Italy’s deep south where it’s warm almost all year-round – and get paid to do it?

For those willing to take the plunge, it could soon no longer be just a dream.

The region of Calabria plans to offer up to €28,000 ($33,000) over a maximum of three years to people willing to relocate to sleepy villages with barely 2,000 inhabitants in the hope of reversing years of population decline.

These include locations near the sea or on mountainsides – or both.

This isn’t money for nothing, however. To get the funds, new residents must also commit to kickstarting a small business, either from scratch or by taking up preexisting offers of specific professionals wanted by the towns.

There are a few other catches, too.

Applicants must take up residency and – sorry boomers – be a maximum of 40 years old. They must be ready to relocate to Calabria within 90 days from their successful application.

It’s hoped the offer will attract pro-active young people and millennials eager to work.

Gianluca Gallo, a regional councilor, tells CNN the monthly income could be in the range of €1,000-€800 for two to three years. Alternatively, there could be one off funding to support the launch of a new commercial activity – be it a B&B, restaurant, bar, rural farm, or store.

“We’re honing the technical details, the exact monthly amount and duration of the funds, and whether to include also slightly larger villages with up to 3,000 residents,” he tells CNN. “We’ve had so far a huge interest from villages and hopefully, if this first scheme works, more are likely to follow in coming years.”

New life

Dubbed “active residency income,” the project aims to boost the appeal of Calabria as a spot for “south-work” – the rebranded southern Italy version of remote working – explains Gianpietro Coppola, mayor of Altomonte, who contributed to the scheme.

He says it’s a more targeted approach to revitalizing small communities than the one euro house sell offs that have recently hit headlines.

“We want this to be an experiment of social inclusion. Draw people to live in the region, enjoy the settings, spruce up unused town locations such as conference halls and convents with high-speed internet. Uncertain tourism and the one euro houses are not the best ways to revamp Italy’s south,” says Coppola.

The “active residency income” project – and application process – are expected to be launched online in the next few weeks. The region has been working on it for months and has already earmarked more than €700,000 for the project.

The region of Molise and the town of Candela, in Puglia, have adopted similar schemes in past years as an alternative to selling crumbling homes for the cost of an espresso.

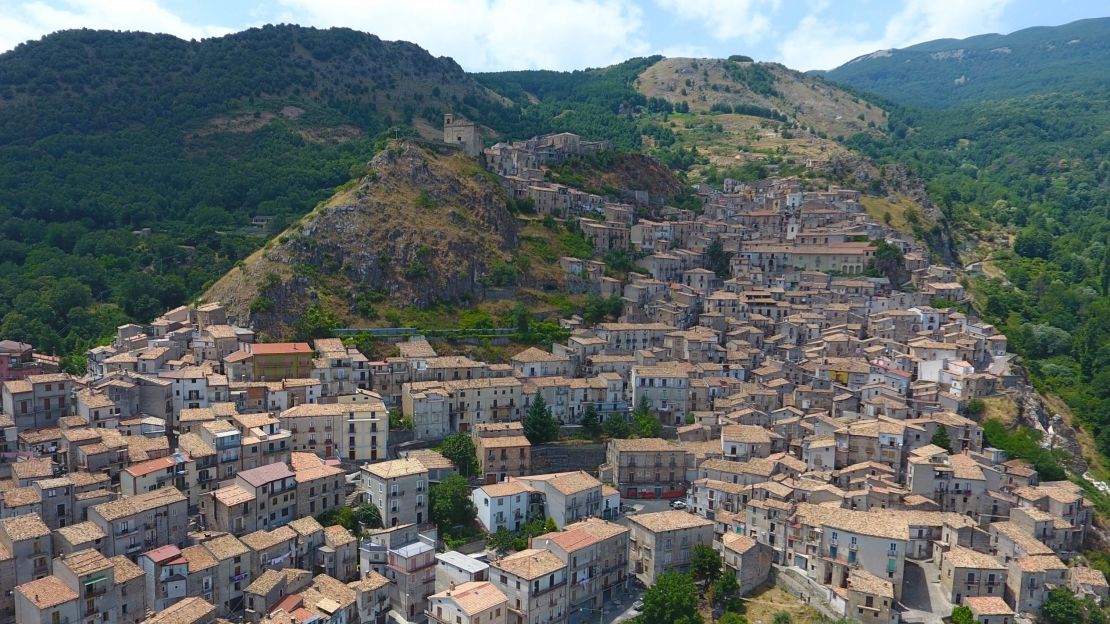

Over 75% of Calabria towns – roughly 320 – currently have fewer than 5,000 residents, leading to fears that some communities could die out completely in a few years unless regeneration occurs.

“The goal is to boost the local economy and breathe new life into small-scale communities,” adds Gallo. “We want to make demand for jobs meet supply, that’s why we’ve asked villages to tell us what type of professionals they’re missing to attract specific workers.”

As global travel resumes and Italy welcomes back tourists, visiting the region this summer might be a good way to get a feel of the Calabrian village life.

Here’s a roundup of the most picturesque places you might end up living in.

Civita

At first even Italian speakers might feel a little lost here. Locals speak a weird-sounding slavic dialect called Arbereshe.

The community was founded in the 1400s by Albanians fleeing the Turkish empire.

Perched on a rocky cliff within the wild Pollino national park once inhabited by bandits and outlaws, this tiny hamlet of barely 1,000 people is what “authentic” Calabria is all about.

The Raganello river gorge, Italy’s largest canyon, is dotted with human-shaped rocks.

A serpentine path goes down to the “Devil’s bridge.” Old traditions, Byzantine rituals and peculiar foods live on.

Old houses are connected by circular narrow alleys dubbed “wrinkles” and have scary-looking chimneys believed to keep evil at bay.

Samo and Precacore

You’ll get the thrill of living in two ancient hamlets at the same time here. Samo was founded by ancient Greeks looking for shelter on the hills but not too far from the shore, turning the village into their “harbor.”

Time stands still.

In the morning the smell of newly baked bread and fresh cheese wafts over the village as women leave their low-cut peasant stone houses carrying baskets of food on their heads, just like in the old days.

The best part of Samo is its sister-ghost hamlet of Precacore, rising right in front over the valley. From Samo’s main piazza a little winding road departs uphill to the abandoned district.

Locals fled following a series of quakes but today Precacore has been brought back from the grave and comes to life during summer.

Hikers, tourists and descendants of former families flock here to admire the Greek-Byzantine ruins.

Aieta

Founded on the ashes of a Greek settlement, the village lies close to the cozy beaches of Maratea and Praia a Mare.

It’s tiny but elegant. Dwellings with red tiled roofs are clustered at the feet of a majestic fortress with panoramic loggia.

Renaissance palazzos and lavish stone portals offer a glimpse of Tuscany in Calabria.

Eagles and wolves inhabit the woods. Trekking routes lead to the nearby villages of Papasidero, Laino Borgo and Laino castello.

Bova

Legends says an Armenian queen built this village on a hill where cows grazed – hence the name which nods to the term “cattle” in Italian (bue).

Known as the region’s “natural balcony” for the mesmerizing coastline scenery, it’s located right on the tip of Italy’s boot close to Sicily, in the heart of “Greek Calabria” which flourished with settlers from ancient Greece.

Noble stone mansions with elaborate portals are situated below the cliffhanging ruins of a Norman castle.

Strolling through the narrow alleys you can still hear the clacking of old looms. Weaving tradition dates back millennia, and the unique fibre broom plant is still picked on the peaks of the nearby Aspromonte mountains.

Fresh goat milk is on sale each day. Ethnic music festivals, a Byzantine Easter party with fruit decorations and a picturesque carnival are top events.

Caccuri

This spectacular hilltop castle, built as a lookout post against pirate raids, overlooks a maze of alleys, stone homes and tiny piazzas with private entrances.

Across centuries powerful feudal families ruled over the village, killing and poisoning each other.

Olive groves dot the hills and produce a premium extra virgin olive oil. Part of the fortress, featuring high walls and a loggia tower hiding inside a cistern, has been turned into an elegant designer resort.

Albidona

Set at an altitude of 850 meters but with territory stretching all the way to the sea, this community enjoys an enclosed pinewood and a cozy beach featuring a Saracen tower.

It’s close to the border with Basilicata and Puglia, making it an ideal spot for touring all three regions and getting the most from the Pollino national park and the warm sunny coast.

With a 10-minute car ride locals can hop downhill for a swim or uphill for a refreshing yoga or trekking session.

Legend says it was founded by a blind seer fleeing from burning Troy. Ruins of a crumbling castle overlook cherry, almonds, and wild apple orchards. The terrain is made of the same stuff as that of the Ionian Sea in Greece.

Sant’Agata del Bianco

A rural vibe survives in this collection of humble peasant dwellings where thick yellowish stone walls and painted green doors whisk tourists back into the past.

The entire village and its rough cobble alleys have been neatly restyled. The local “Palmenti Route” trail takes in a network of old wells cut into the rocky ground and once used to make wine.

Dating back to Greek and Byzantine times, these are an open-air piece of history. Colorful wall paintings show poem verses, faces of smiling children and people drinking at the bar.

Fun attractions include the wine museum and the museum of “lost things” belonging to the rural world.

Santa Severina

This village rises on a tuff rock cliff overlooking the Neto River. It’s built in layers depending upon wealth: palazzos belonging to the richer families are at the top of the hill, the humble dwellings below, dug into the rock.

There’s a Greek and Hebrew district with palm trees.

The baptistery here is the oldest Byzantine monument in Calabria, while the impressive well-kept castle features frescoed undergrounds and stables.

Santa Severina is known for its oranges. Villagers are dubbed Aranciaru, meaning “orange-eaters” in local dialect. Oranges grown here are the pride of Calabria, due to the fertile soil and exceptional nutritional qualities. They’re sought after in top restaurants and fruit shows.

San Donato di Ninea

Dating back to before Greek colonization, this charming village lies in the deepest area of Calabria’s Pollino national park.

It’s so remote and tucked away on the hills that barely anyone outside of Calabria knew it existed up until the 1970s.

The view from high up on the peaks takes in the region’s two seas: the Ionian and Tyrrhenian.

This untouched and pristine location is home to many wild animals and plants and is considered one of Italy’s top wilderness reserves.

Orchids grow along mountain trails unwinding to panoramic huts. It’s a chestnut heaven with popular food fairs.

Keep an eye on the region’s website for news of the project.