The global aviation network system is turning into a frantic game of musical chairs.

Every player is orbiting over its landing site. The music stops, the there’s a mad dash for somewhere to park.

At any given time – pre-coronavirus era – there were usually as many as 20,000 planes swirling around the planet at altitude. The system isn’t designed for that amount of planes to be anywhere else apart from in the air – the only place they generate revenue.

Parking at airports is also pricey. Major European hubs can charge in the region of $285 an hour.

Airlines hit the pause button

Earlier this month, the music stopped abruptly with population lockdowns dominoing across the world. The whine of airplane engines was rapidly muted into an eerie silence.

Some airlines are operating just a skeleton service, and the massive reduction of transatlantic flights in mid-March has kick-started a chain reaction of airplane groundings.

Delta Air Lines has instigated a 70% system-wide pullback, parking at least half of its fleet – more than 600 aircraft. “We also will be accelerating retirements of older aircraft like our MD-88/90s and some of our 767s,” the airline’s chief, Ed Bastian, said in a memo to Delta employees.

Australia’s Qantas is temporarily grounding 150 airplanes, a mix of A380s, 747s and B787-9s. The carrier says discussions are progressing with airports and the government about parking for these aircraft.

Qantas boss Alan Joyce noted that “efforts to contain the spread of coronavirus have led to a huge drop in travel demand, the likes of which we’ve never seen before.”

In Germany, Lufthansa Group is reducing seating capacity on long-haul routes by up to 90%. And for its 29 March to 24 April timetable it announced that a total of 23,000 short, medium and long haul flights were being canceled.

Europe’s low-cost carrier Ryanair expects to reduce seat capacity by up to 80% over April and May, and admitted in a company statement that “a full grounding of the fleet cannot be ruled out.”

With so many major airlines reducing capacity, where will all those planes be stored?

At such a sensitive time, many storage facilities are being justifiably discreet. No one wants to be misconstrued as doing business at the expense of the airlines’ misfortunes.

The logistical complexities of where to park thousands of airplanes is made even more complicated by the technicalities required when storing planes.

To ensure they are stored in a way that enables them to return to service in tip-top condition when flights eventually resume, a kind of aeronautical embalming process is required.

This involves draining various fluids, covering the engine intakes and exhaust areas, protecting external instruments like pitot tubes (used for monitoring the airplane’s speed during flight), covering windows and tires – along with other tasks specific to each plane.

Go West

Just north of the Catalina Foothills of Arizona lies Pinal County Airpark, originally set up as a facility in the 1940s for training military pilots. Today the airpark provides a range of storage and heavy maintenance services for wide-body commercial jets.

The airpark has 500 acres suitable for airplane storage, the cost of which depends on a matrix of factors – how big the plane is, and then what additional “extras” the owner/operator wants.

“If the customer wants it kept airworthy and up-to-date with minimal time for reactivation, it runs higher than just storage because there are so many things that the aircraft specifically needs done,” says Jim Petty, the economic development director for the airpark.

If the aircraft is parked and not managed, the costs are reduced. Generally the airport will lease land to storage companies that then provide the storage services to the ultimate customer.

Petty tells CNN Travel that average rates for monthly parking fees charged in the Southwest area are in a range that is segmented by aircraft weight categories. These span between $56.50 per month for 12,500 lbs – 24,999 lbs, to $300 per month for between 100,000 lbs - 200,000 lbs.

These, he points out, are the rates charged by the airport for each aircraft and not necessarily the rates charged by the airport storage businesses which are higher, to account for added services.

Why is America’s Southwest an attractive destination for airliner storage? One of the main advantages is the arid climate.

“That helps to retard corrosion,” says Petty. “Another reason is the relative openness of the region. That’s why other airports in the vicinity offer the same services.”

Pinal County Airpark also has tenant businesses that provide one-stop shopping – they can store aircraft and handle them from landing to departure back into service, and are able to manage and reactivate and perform any type of maintenance on the aircraft.

Borderline decision

Over the border in New Mexico, the Roswell International Air Center is in the process of adding 300 more acres of asphalt parking space to its existing 4,000-acre footprint – enough space to accommodate up to 800 airliners.

“We’re working with local companies here at the air center that currently have over 200 planes parked here to reposition and nest aircraft together to maximize available parking areas,” says Mark Bleth, air center manager and deputy director at Roswell.

Storage prices are set by the City of Roswell’s resolution 10-25, with three price ranges depending on size of aircraft. Planes up to 99,000 lbs are charged at $7/day; medium sized aircraft between 99,001 - 200,000 pounds, $10/day; and large airplanes over 200,000 lbs are $14/day.

“This is what we charge our tenants that are accepting these aircraft on behalf of an airline,” Bleth tells CNN. “But what they’re billing won’t be the same because of added services they provide.”

The pricing was set 10 years ago and was scheduled to be updated. However, Bleth emphasizes that, “We don’t want to add any additional costs to the airlines, so we will hold our pricing until the [coronavirus] event is over.”

Runway model

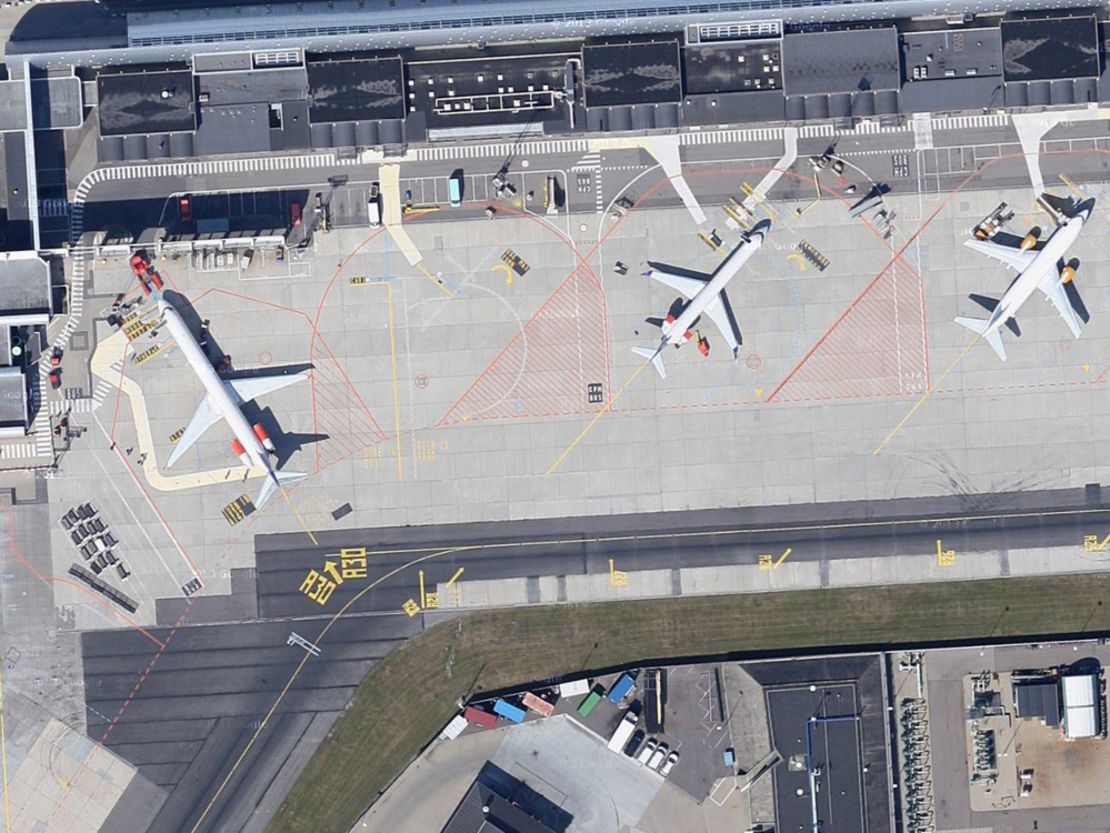

At Copenhagen Airport in Denmark they’ve come up with a different solution for generating new parking capacity.

Two of the airport’s three runways have temporarily been decommissioned and are being used to accommodate airplanes, leaving runway 22L/04R active for all takeoffs and landings.

Dan Meincke, chief of traffic at Copenhagen Airport (CPH) tells CNN that with the current scheme they expect to be able to accommodate about 60 aircraft on the two deactivated runways, in addition to the 80 aircraft that are normally parked at the airport’s regular aircraft parking stands.

“Our aircraft storage scheme is designed to allow airlines the greatest flexibility possible for retrieving a single aircraft when it’s needed in operation or for maintenance,” says Meincke. “This flexibility somewhat reduces the total capacity but if airlines request more parking spots, we can change the scheme dynamically.”

Operating an airport with only one of the three runways serviceable has created somewhat of a challenge, with some extra planes also being parked on the taxiways. So there’s a balance to be struck between parking and still maintaining flight operations.

“We don’t consider the parked aircraft a problem right now,” says Meincke. “In the current situation we will do everything possible to park as many aircraft as possible and we’ll negotiate terms on a fluid basis with airlines, but at the moment both short and long-term aircraft parking is an option.”

Currently CPH is running with approximately 58% less takeoffs and landings than usual (figures as of March 19). Yet, while the airport prioritizes resources to assist those airlines that are its regular customers, the airport says it’s ready to discuss terms and try its utmost to assist any airline that has a need for aircraft storage in Copenhagen.

A global challenge

The world of aviation storage has to cope with grounded planes from all over the world – the Asia-Pacific region included.

In Australia, former Deutsche Bank vice president and research analyst Tom Vincent set up a storage facility called Asia Pacific Aircraft Storage (APAS) over a decade ago at Alice Springs. It is in the process of expanding its capacity footprint from the present 30 planes to 70.

“The climatic conditions are ideal for aircraft asset value preservation, with extremely low humidity,” Vincent tells CNN Travel. “Storage in high humidity environments such as Asia can have very adverse ramifications on the aircraft, particularly engine and airframe corrosion.”

That could be of interest to airlines specifically located in and around the original epicenter of the coronavirus.

With airlines not knowing how long their planes might remain inactive, Vincent says that customers can choose from a range of storage programs, “ranging from relatively short-term parking 3 to 6 months, or longer-term programs.”

Final call

The biggest unknown at the moment is how long it will be until travel restrictions are lifted and airlines can start flying again.

The massive hit to everyone’s pocket could mean that consumer demand for flying could take a long time to regain momentum before returning to pre-Covid 19 traffic levels.