With decades of experience in the kitchens of luxury hotels in South Korea, the United States and the United Arab Emirates – where he served as head chef at Burj Al Arab – celebrity chef Edward Kwon has proven that he’s comfortable in a toque and apron.

But he’s also demonstrated skills as a savvy businessman, whether as the star of a Korean cooking show, the author of multiple books or the CEO of food and dining company EK Food.

But before Kwon’s culinary career kicked off – he’s founder and head of restaurant Lab XXIV in Seoul and Elements by Edward Kwon in Moscow – he had a different plan for his life.

“Please don’t laugh about it – I wanted to be a priest when I was a kid,” Kwon tells CNN.

Kwon is still devoted to preaching – but these days he’s singing the praises of Korean food.

“I’m trying to globalize Korean food,” he says.

Kwon, 45, has transformed his name into a Korean culinary brand with global clout, but it was only through a series of fortunate accidents that he stepped into the world of food.

“Becoming a chef was never my dream,” says Kwon.

“I had to feed myself, however, so I ended up working at a restaurant.

“My first job was as a dishwasher, then a server and at this point I had no desire to work in the kitchen.”

It was only when a coworker informed him that cooks were paid more than servers that Kwon decided to change jobs.

Bittersweet overseas success

After working a few years at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in Seoul, Kwon, then 29, took a job at the Ritz-Carlton San Francisco – even though he was unable to speak a lick of English.

“I was ready to die,” says Kwon of his experiences in the aggressively competitive kitchens abroad, where he dealt with racial slurs on top of the language barrier.

Today he speaks English fluidly and with character, if not native fluency.

But English isn’t the only thing he gained from his time abroad.

Kwon says he’ll always appreciate the importance of learning through travel.

“A chef is on a culinary journey until the day he dies,” he says.

“It might be a journey to look for ingredients, or to eat out at a restaurant or even to eat street food. There’s always a learning opportunity.”

But success overseas was bittersweet.

“Because I’ve lived abroad for a long time, the media sometimes implies that I had an advantage because of my overseas experience,” says Kwon.

“People have these misconceptions, thinking that I’m from a wealthy family, and had a lot of other advantages.”

Kwon resents any suggestion that somehow he’s less Korean for his stay abroad, or because he uses an English name.

“This kind of thing can be demoralizing for people who go abroad to study.

“A lot of the media comments can be hurtful. These people went abroad to learn, not to gain an unfair advantage.”

Unofficial ambassador for hansik – Korean food

Kwon was trained as a hotel chef and his main game is French.

Even his restaurant in Seoul serves French.

But abroad, Kwon is active in promoting Korean food – called “hansik” – and sees himself as an unofficial ambassador for his homeland’s cuisine.

The Moscow-based Elements by Edward Kwon and his upcoming St. Petersburg restaurant serve Korean cuisine.

“Now a lot of people are getting interested in Korea, especially Korean drama and K-pop,” says Kwon.

“But they don’t really know about Korean food.”

Kwon believes that food should lead the Seoul government’s attempts to promote Korean culture abroad.

“With music or movies, people can change their minds the next day. But the memory of food lasts.”

“As one of the Korean chefs most well-known abroad, I want to act as a liaison,” says Kwon.

There’s still a long way to go.

“One of the reasons I want to globalize is that I want to show that there’s more to Korean food than Korean barbecue,” says Kwon.

“Ten times out of 10, people will order Korean barbecue. But when friends visit from abroad, I’ll take them to have ugeoji haejangguk and they love it.”

Haejangguk refers to a family of soups that often include ox blood as an ingredient, and literally means “hangover cure soup.”

Ugeoji is the dried outer leaves of a Napa cabbage.

Korean through and through

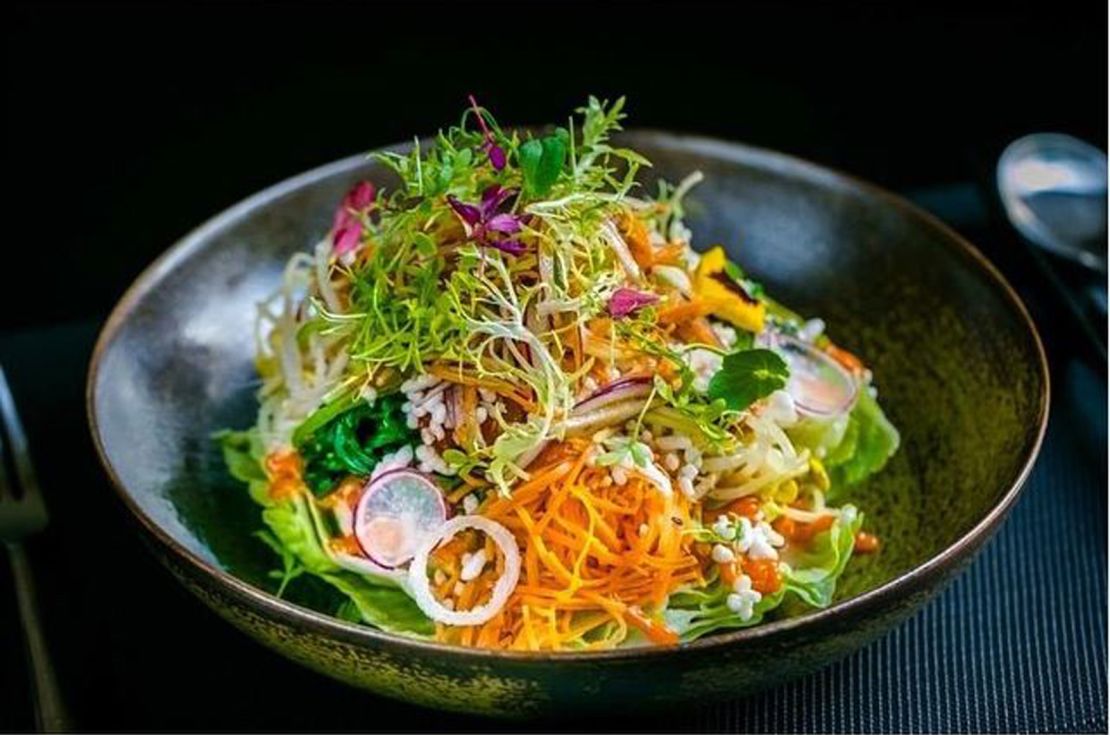

Kwon is quick to emphasize that the food he serves at international gala dinners is Korean through and through, despite the hotel setting and unorthodox plating.

When cooking Korean, Kwon stays true to traditional seasonings and bases and tries to stick to Korean ingredients.

The style of presentation is a practical decision, because hansik often requires individual sets of dishes for the banchan (side dishes) or silverware that most hotels don’t have on hand.

“You can put a twist on Korean food. But a Korean should be able to eat it and say, ‘Yes, this is Korean food.’”

The food at Elements follows this principle.

Kwon shows a photo of a dish that looks like a miniature garden, featuring some sort of wrap in the center, topped with a half-done egg.

“This is yukhoe,” says Kwon.

Yukhoe is Korean-style beef tartare. It’s unrecognizable in the photo.

“Usually in Korea it’s served with pine nuts, and julienned,” says Kwon.

“But I changed the way it looked on the plate. But when you dig in, it’s yukhoe. It’s just shaped differently.”

He flips through a series of photos, all featuring unrecognizable, but attractively presented renditions of mandu (dumplings), ddeokbokki (rice cakes in a soy sauce or red pepper paste-based sauce) and tofu kimchi.

“The most important thing is that my Korean food is reinterpreted in a modern way, but that in the taste and the roots, it’s perfectly Korean,” says Kwon.

“If you don’t protect your roots, the globalization of Korean food is meaningless.”

Got photos of your own Culinary Journeys to share? Tag them on Instagram with the hashtag #CNNFood for a chance to be featured on CNN. For inspiration, check out these recent submissions.

Violet Kim is a freelance writer based in Seoul. Find her online @pomography.