Architect Teddy Cruz is frank: “In this day and age, we are not proud of what is going on in the United States,” he said, referring to himself and his long-term collaborator, Fonna Forman.

The sentiment is not unexpected from the Guatemalan-born American architect who, with Forman, a political scientist, has long explored citizenship and urban dynamics at the United States-Mexico border, and the ecological, humanitarian and economic threat it poses in its militarized state. But it’s not something you expect to hear at the US Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale, funded in part by the State Department.

Highlights from the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale

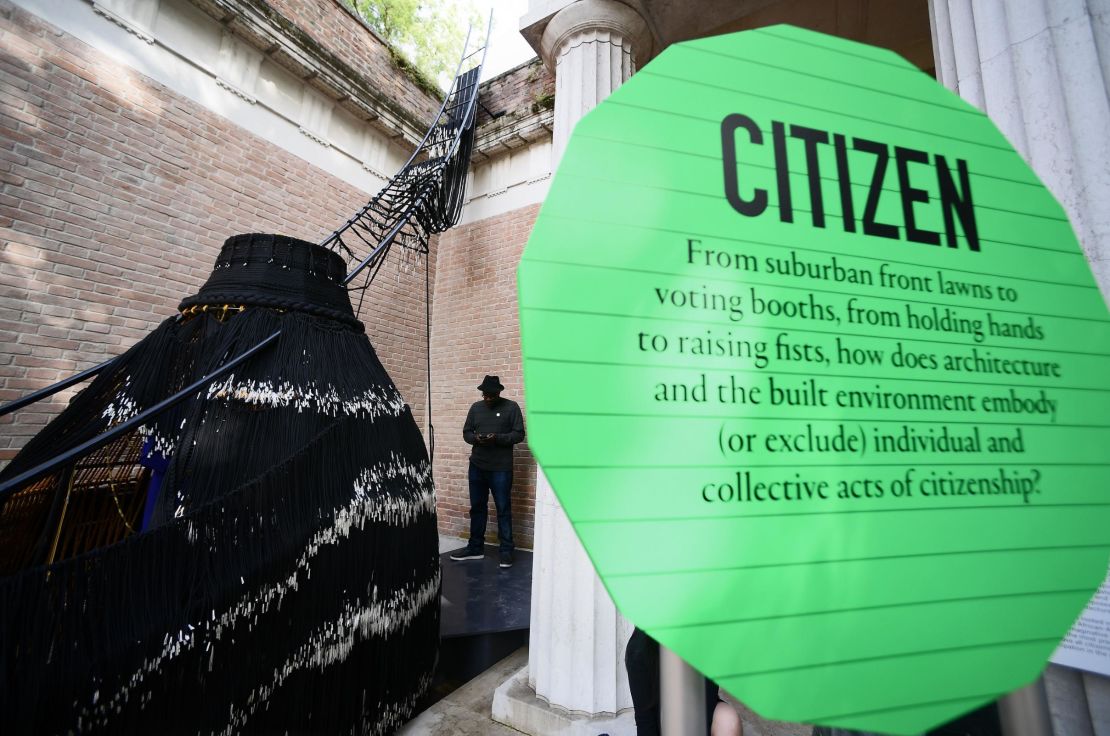

The most important event on the international architecture calendar, the Biennale is where nations have sent their greatest thinkers to hash out the most pressing themes and issues gripping their industry – and society at large. So, it was perhaps inevitable that the shadow of the Trump administration would loom dark over the American exhibition. Titled “Dimensions of Citizenship,” it sees Cruz and Forman, among many others, interrogating what it means to occupy different spaces – a body, a region, a nation, a planet.

This year’s Biennale theme, “Freespace,” feels particularly poignant at a time when many Americans feel as though their freedoms – or the stories they tell themselves about what it means to live in the Land of the Free – are under threat.

The contrast between the research and artwork displayed on the walls of the Palladian-style US Pavilion and the rhetoric from the White House is overt. In the courtyard, a rope-and-steel braided installation, a tribute to the value of black lives from artists Amanda Williams, Andres L. Hernandez and Shani Crowe, jars with President Donald Trump’s defense of white nationalists as “some very fine people.” Inside, SCAPE Studio’s display showing the devastation human intervention has wreaked on marshlands in the US and abroad sits uneasily with Trump’s anti-regulatory environmental agenda.

“I think for all of us in the discipline, we as citizens had concerns and feelings about the kind of troubling administration and the questions about belonging that emerge in the wake of the inauguration, and so we’re really grateful for these kind of practices to both situate those questions in a longer history, and also start to move us forward and give us framework for talking and working on these things moving into the future,” said Ann Lui, an assistant professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and one of the curators of “Dimensions of Citizenship.”

“They’re not just antagonistic. They bring in a rich and nuanced discussion that is often lacking from the national conversation.”

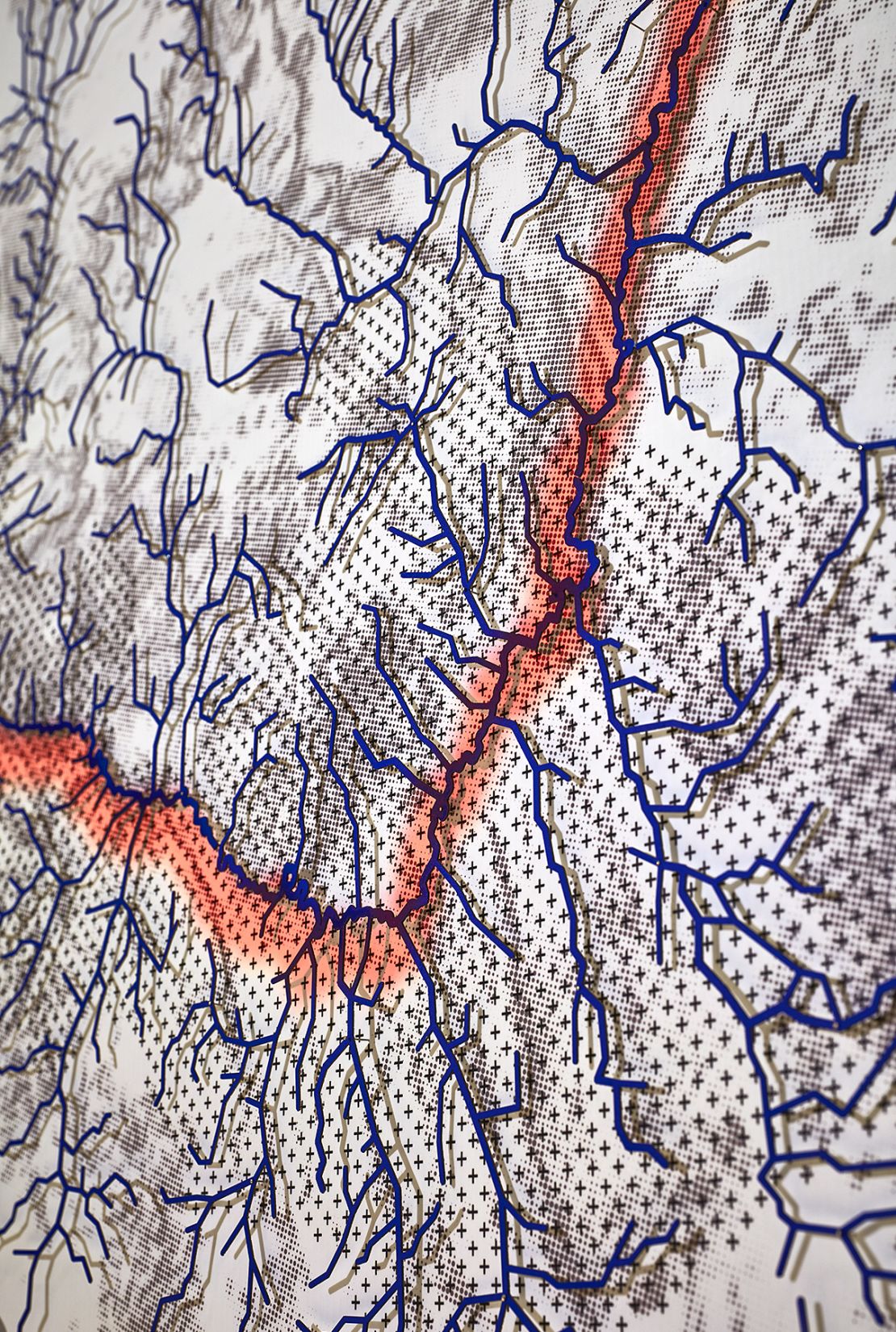

None of the presentations seem as paradoxical as “MEXUS: A Geography of Interdependence,” Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman’s deep dive into the ecological regions along the US-Mexico border, given Trump’s border wall promises and anti-Mexican statements. In a simple display, primarily using information boards and a projected topographical map, they show how the border has bifurcated eight watersheds, and outline the negative effects of US infrastructure built along this demarcation – particularly how it has affected areas like water management in both countries, and American ecological conservancy efforts.

“What we’ve tried to do in ‘MEXUS,’ in this intervention, is to reimagine the border zone not as a line, not as a jurisdictional boundary, but as a region that shares many ecologies and lots of movement back and forth on both sides – people, environmental flows, economic flows, emotional and ethnic flows and so forth; to reimagine these regions as places of potential collaboration and interdependence,” said Forman.

“We’ve tried to take the idea of citizenship back, untether it from the idea of the nation-state and expand it into a more ethical concept and practical concept of interdependence.”

To Cruz and Forman, this focus on the ecological element is part of a broader goal to reframe how the public perceives the border and, consequently, the people living on the other side of it. Inspired by the work of former Bogota, Colombia mayor Antanas Mockus, a friend who championed a model of civic engagement tied to culture and education, they hope their work will “change hearts and minds” and, eventually, influence public policy.

“We work a lot at times oscillating between architecture and art and we realize that many artists at this moment want to engage very ephemeral interventions into the territory or into the city just as acts of protest, but at times we have felt uncomfortable with the ephemeral nature of these works that, at times, do not amount to very much, even though it is essential to have such instances of protest,” Cruz said.

“The border has been sold to the American public as an artifact of security when, in fact, we can prove that it’s an artifact of insecurity, environmentally and socioeconomically. So, this whole idea of how to transform the mythologies that have perpetuated fear and division needs new tools of engagement and forms of cross-border education.”

So far, their efforts seem to have had some success. According to letters displayed at the Biennale, government agencies and academics across the border of Tijuana and San Diego, where Cruz and Forman teach at the University of California, have voiced support for the development of a cross-border conservation plan to protect the Tijuana River Valley.

A different type of reframing is taking place at the British Pavilion, where Caruso St John Architects and artist Marcus Taylor are countering the Brexit-era rhetoric of isolationism and nationalism with a striking gesture. Instead of setting up an exhibition, the curators left the pavilion, idyllically located on a hill overlooking the Giardini, empty, and have instead erected “Island,” a sparse, scaffolding-supported rooftop platform to be used as a communal space for visitors and delegates from all countries.

“We’re offering this space to Venice and to this Biennale at a time when Britain is so completely ambivalent in terms of signals,” said Adam Caruso, a co-founder of Caruso St John Architects, who immigrated to London from Montreal 34 years ago.

“In and amongst all of this ambiguity and conflicted signals, we’re trying to do something that is genuinely open and generous because, I think, Britain, until recently, has been to do with tolerance and has been a place where immigrants have escaped to and their contribution has been recognized.”

This idea of inclusion is further explored in the accompanying book, also titled “Island,” that includes short stories from Trinidad-born author Sam Sevlon, one of the first novelists to give a voice to the increasingly beleaguered Windrush generation, previously unreleased photos from Ghanaian-British artist John Akomfrah, and a full script of Shakespeare’s “The Tempest.”

Architect and curator Kerem Piker has staged a similarly international project at Turkey’s pavilion in the Biennale’s Arsenale venue. Over the next six months, 122 architecture students from 16 countries will meet in small groups to build connections and develop installations that riff on various architectural themes.

“The idea of the Biennale is to unite. So instead of limiting it only within the nation, we wanted to keep it open. We wanted to be a part of the culture,” Piker explained. “That’s why we don’t need boundaries.”

Back at the US Pavilion, Teddy Cruz summarized his feelings – and, likely, the feelings of exhibitors in pavilions across the island – on the role of such displays on the world stage.

“(Our exhibition) is emblematic and symbolic of the hope that can be opened up through art, sculpture and other sectors that really should continue engaging and fighting against those positions,” Cruz said.

“Architects more and more need to take a political position against what is morally and ethically wrong.”

La Biennale di Venezia is on until Nov. 25, 2018.