Chinese skylines have been subjected to tremendous change over the past decade. Heritage sites and huge swaths of traditional housing have been razed and replaced with soaring towers symbolizing wealth, development and power.

With hundreds of millions of people set to migrate from rural areas to cities by 2020 as part of the Chinese government’s ambitious urbanization program, the number of skyscrapers built to accommodate them will continue to grow – but not necessarily in an imaginative way.

'MAD' visions

Utilitarian housing and office blocks are the hallmark of burgeoning cities in China. Megacities like Beijing are already overrun with them, creating cityscapes that feel “artificial,” as Beijing-based architect Ma Yansong observes.

“I think in our modern cities there are a lot of boxes; there are a lot of straight lines,” he says. “They often deal with efficiency, the function, the structure.

“There’s no nature. People love to go closer to nature and other people, so we need to create environments that let people have these emotional connections.”

Emotional architecture

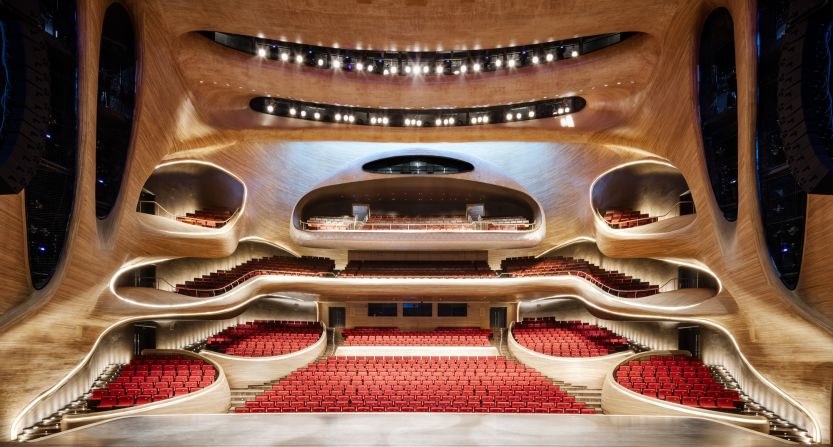

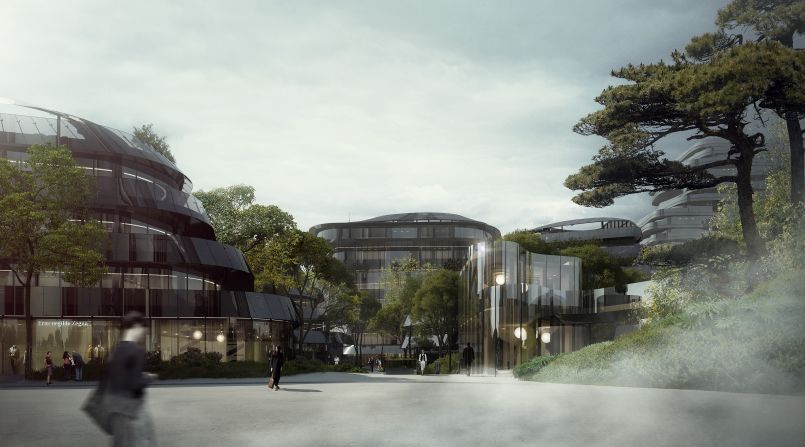

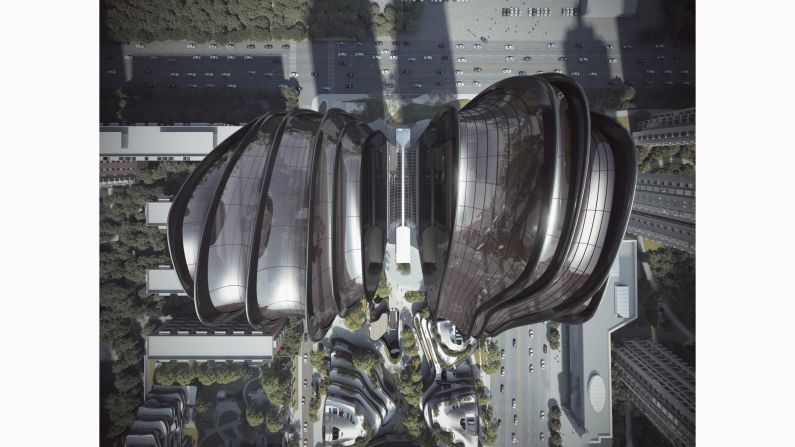

Ma, the founder of the world-renowned MAD Architects, has built a poetic portfolio of buildings that adhere to his “Shanshui City” design philosophy. “Shanshui” which translates to “mountain, water” embraces the integration of organic forms and Eastern design principles, emphasizing nature at the core of urban planning.

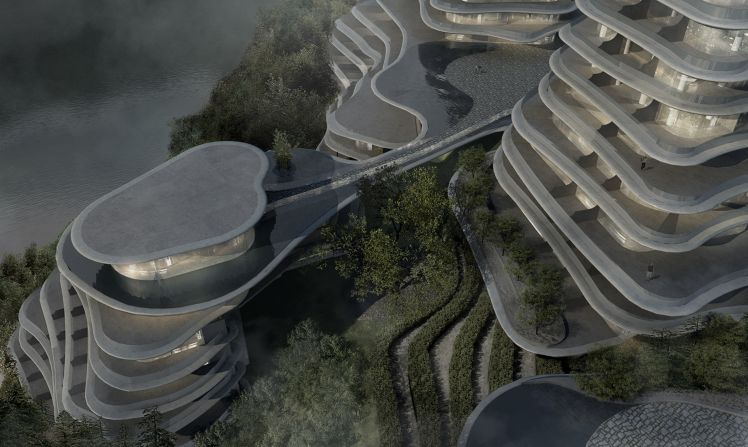

New photos of MAD’s Huangshan Mountain Village, in China’s Anhui province, show an undulating range of apartment complexes, a nod to the nearby limestone terraces of Huangshan (“Yellow Mountain”).

Huangshan Mountain Village

In cities, Ma has often disrupted the usual “emotionless” lines and “industrial curves” to create structures influenced by Chinese classical paintings, the extreme curves of mountains, the gentle lines of the desert and even (in the case of the voluptuous Absolute Towers in Ontario, nicknamed “Marilyn”) the human body.

Future of cities

Although China was once considered to be an architect’s playground, the country’s economic slowdown – coupled with President Xi Jinping’s aversion to “weird architecture” – means that the future of its cities has yet to be written.

“In traditional cities like Beijing, Nanjing and Hangzhou, nature was a very important part of urban planning. Not only as a landscape, but a part of daily life,” Ma says. “It’s a beautiful garden, let’s say. But they were all low density.”

Ma wants to apply his Shanshui City philosophy to the expanding cities of the future.

“There must be some new way (in which) we can have high density and, at the same time, have a beautiful landscape in an urban situation.

“What if we treat the high-rise like a mountain, or we have gardens in the sky, or waterfalls? I think that’s the most challenging thing I want to try in my architecture.”

Watch the video above for an interview with the architect on why curves matter.