Eric Fischl speaks in a measured tone, but the American painter is angry and quietly despairing.

He started doing caricatures of Donald Trump and his inner circle on his iPad during the 2016 presidential election campaign. “It was the only way to understand what was happening. The only way to deal with it through humor. My world – my cohesive, rational world – was falling apart,” he explains.

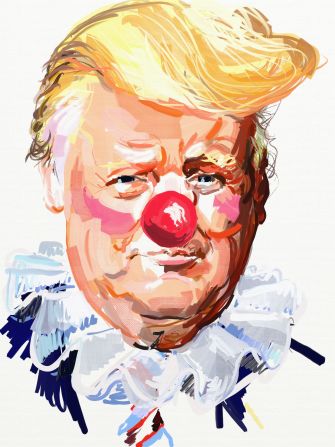

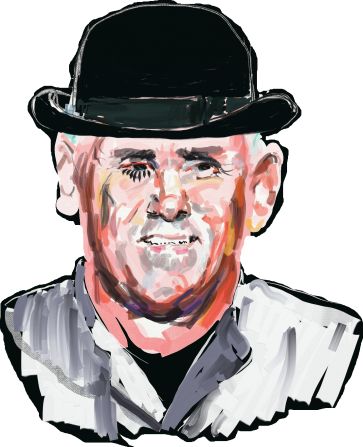

He shows me the results on his phone: a clowns’ gallery of the inner White House, all sporting red comic noses. Trump is depicted with a gaudy yellow surf of hair and a clown’s neck ruffle. The vice president, Mike Pence, wears a bowler hat and a false eyelash, like the sadistic gang leader in Kubrick’s “Clockwork Orange.”

Compared to the savage Trump cartoons of British illustrators like Ralph Steadman and Gerald Scarfe, they seem, perhaps, a little tame. But they evidently served as a kind of therapy. Fischl distributed the caricatures on Facebook and Instagram. He didn’t regard them as art.

Fischl abandoned the caricatures a few months ago. He felt that he had to stop the caricatures because “we’ve sunk to his (Trump’s) level.” Initially, Alec Baldwin’s Trump impression on “Saturday Night Live” was “a life-saver,” but now Fischl has given up watching parodies on late-night TV. “It’s not funny anymore. It’s fueling my anger.” Just about to turn 70, he says has never felt his country so fractured.

Eric Fischl's iPad caricatures of Trump's ever-changing circle

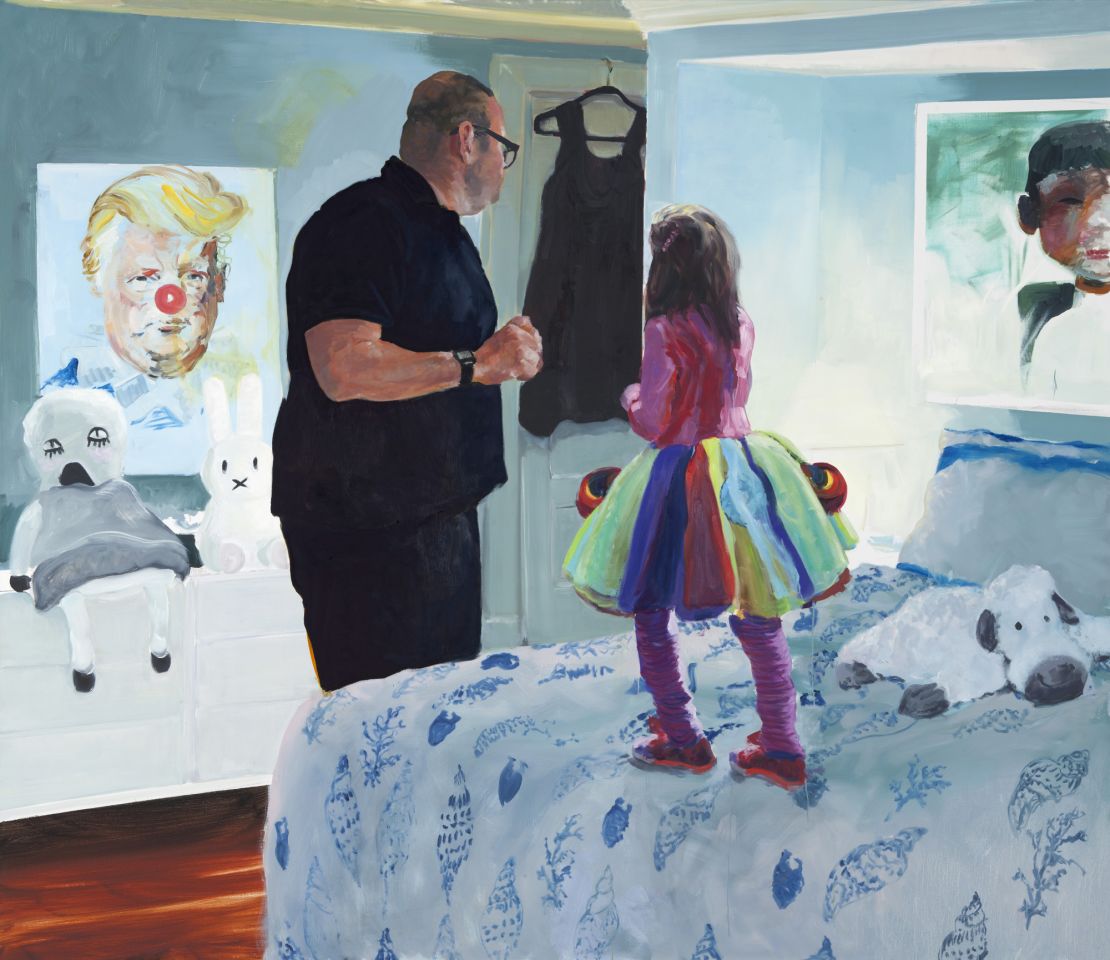

Fischl’s new exhibition at the Skarstedt gallery in London is called “Presence of an Absence.” Inevitably, it seems, Donald Trump has insinuated himself into one of the pictures. It’s called “Worry” and, somehow, it projects a prevailing anxiety.

The setting is a child’s bedroom. The two central figures are turned away from us. A middle-aged man dressed in black looks towards the door. A young girl in party frock is stood on the bed. Looking back at us directly and dead-eyed are Trump, as a clown poster on the wall, and the child’s stuffed toys. A black dress hangs on the door. Ever the narrative painter, Fischl is telling us a story and leaving it up to us to complete it.

In another painting entitled “After the Funeral,” two women sit at a table on a sheltered terraced, lost in shadows and their own thoughts. Both are dressed in black, one half obscured by a cumulus of cigarette smoke, the other offering a consoling white handkerchief.

Why, I wonder, was there so much black in his painting now? “Increasingly,” he says, laughing, “black has become a third character.” Why is that? “For all the reasons,” he replies. “The void, the lightless space, the seriousness, the mourning.”

Fischl claims that he was only taught about abstract art as an art student at the California Institute for the Arts. At 24, he spent more than a year and a half as an attendant at Chicago’s Contemporary Art Museum. Only after this and subsequent study of his heroes, Manet and Degas, did he realize he wanted to be a figurative painter.

In 2014, Fischl told the Guardian he sees himself as a painter in the tradition of Edward Hopper, “trying to create a frozen moment.” And he has been remarkably consistent in his subject: the little psycho dramas of white upper-middle-class suburbia in Long Island, New York, where he grew up and still lives.

Fischl specifically names “Sleepwalker” (1979), an image of a preteen boy either peeing or masturbating in a kiddie pool, as a breakthrough painting. Fischl admits that he consciously did the picture “to get noticed,” but it had turned out to be “a poignant, transitional moment in a boy’s life. Not a dirty picture, but complicated. “Bad Boy” (1981), which he calls his “most famous and notorious painting,” also challenged taboos and hit a nerve. Here, a young boy is standing before a woman, perhaps his mother, sprawled naked on a bed, legs splayed. Behind the boy’s back, he is dipping into her handbag. The room is suffused with soft light coming through orange blinds.

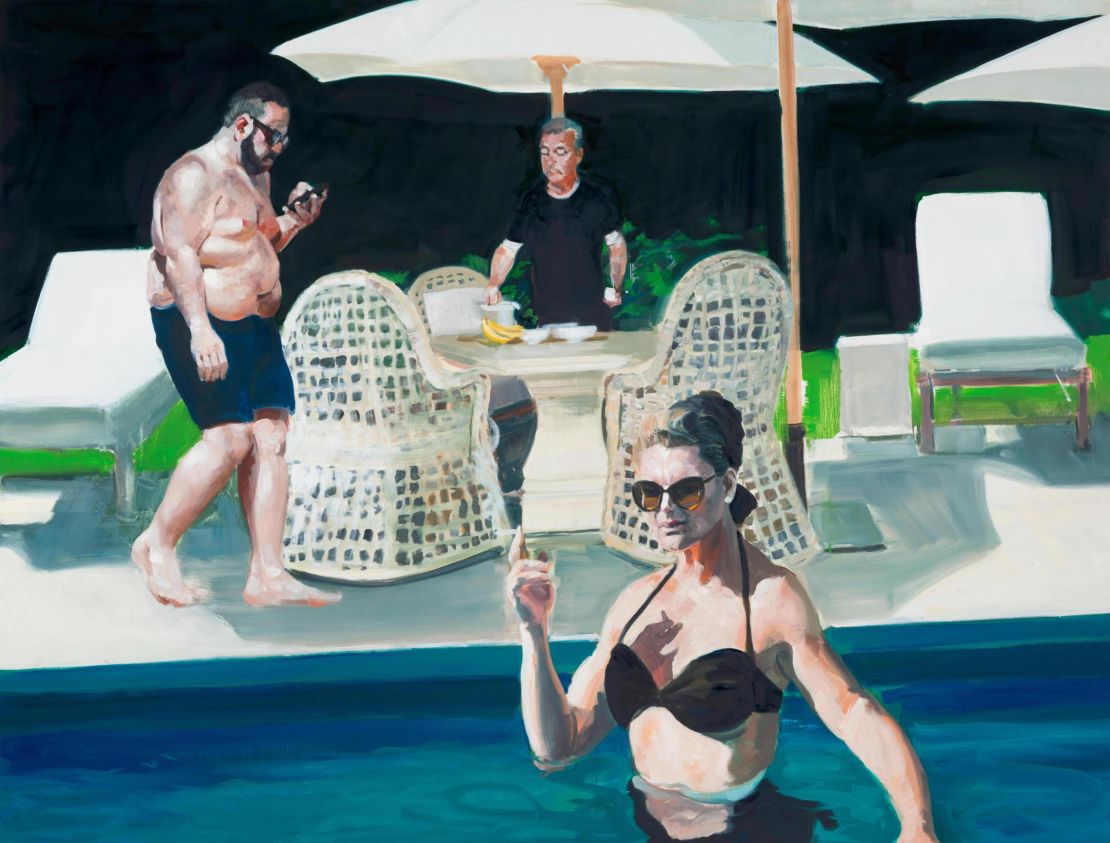

Three of the new paintings on show in London are also set by a swimming pool. In “Clearing the Table,” a man in black t-shirt is clears a meal from a table shaded by a parasol; a bearded, overweight middle-aged man in black trunks walks by the pool, checking his mobile phone. But the central figure is a woman in black bikini and dark glasses, standing up to her waist in the pool, fixing us with what Fischl calls “a ferocious look.” She looks intimidating. We feel as if we’re intruding somehow. Fischl is pleased with the effect, achieved, he says, with just four brush strokes.

From the outset as young artist, he sought to find a subject “big enough to last me a lifetime.” That has turned out to be relationships: men and women, boys and girls, fathers and sons. For Fischl, they are “endlessly complicated and compelling.”

Fischl seems to have done well financially as a painter. He lives with his wife, landscape artist April Gornik, and two Bengal cats in Sag Harbor, Long Island. A decent club tennis player, he’s been known to knock a few balls around with friend John McEnroe. He’s painted portraits of Joan Didion, Paul Simon and Steve Martin, who owns several Fischl paintings. Fischl’s auction record, set in 2006, is $1.9 million. The paintings in his new London show are priced from $750,000 to $850,000.

And yet he remains deeply disturbed about the state of America, about “the fear, the uncertainty, the anger, the affront.” And although he blames the Democrats as much as the Republicans for the current state of affairs, he reserves his greatest contempt for Donald Trump.

“He couldn’t care less about civilization or culture,” he says.

The most memorable image from Fischl’s show in New York last spring was titled “Late America”. A little boy in shorts, wrapped in the American flag, is clutching a teddy bear and standing poolside. He could have been lifted from an illustration by Norman Rockwell except there’s nothing optimistic or sentimental about the boy. Lying in front of him is a naked middle-aged man – his father perhaps. We see him from the rear – a glimpse of scrotum, fattish, sunburned thighs and hairy legs, and the contrasting fleshy whiteness of his bottom. The boy seems expectant, hoping for some communication or comfort. He’s getting no response.

The painting was completed right after Trump was elected, and some people mistook the lying figure for the new president. Fischl says he hadn’t realized the painting would become “so immediately iconic.”

“Eric Fischl: Presence of an Absence” is on at London’s Skarstedt gallery until May 26, 2018.