Editor’s Note: Keeping you in the know, Culture Queue is an ongoing series of recommendations for timely books to read, films to watch and podcasts and music to listen to.

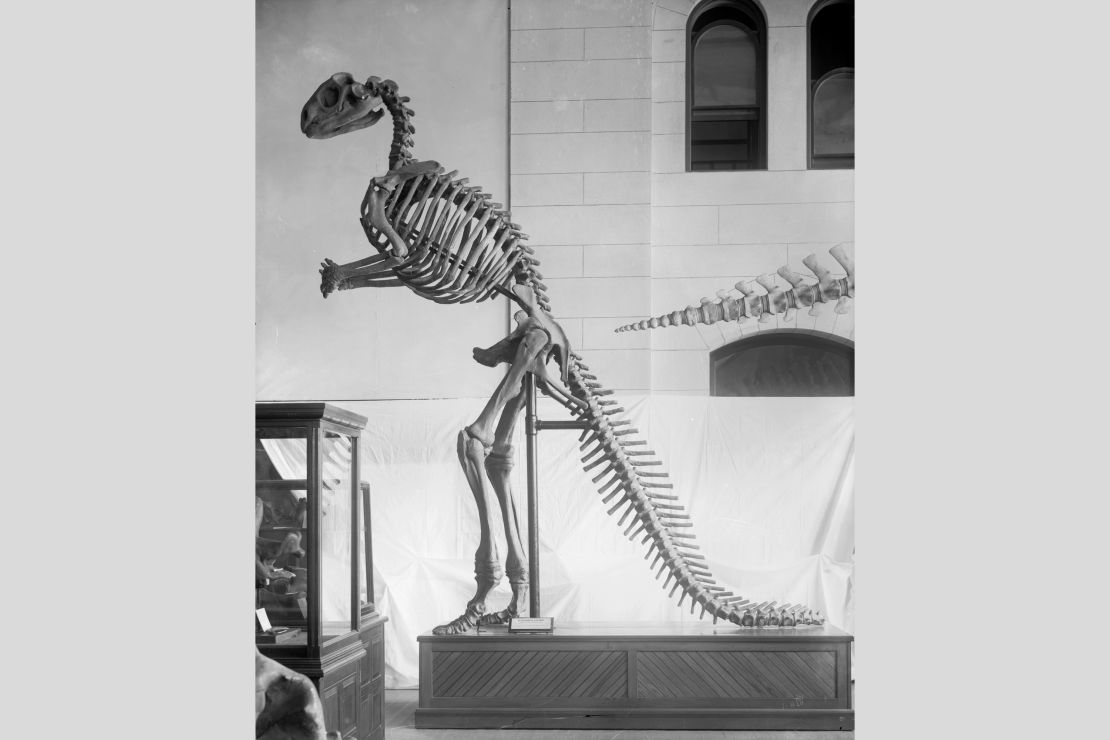

Crystal Palace Park, in south London, still hosts the world’s first dinosaur sculptures. They were created in the 1850s based on what were, at the time, very recent scientific discoveries: fossils, unearthed in England just decades earlier.

Scientists struggled to make sense of the creatures, and the sculptures were the first attempt to visualize them in true-to-life size. They were depicted like giant, mammal-like beasts, heavy set and four-legged – an already revolutionary idea compared to earlier ones that imagined dinosaurs essentially as huge lizards. But it was just as wrong.

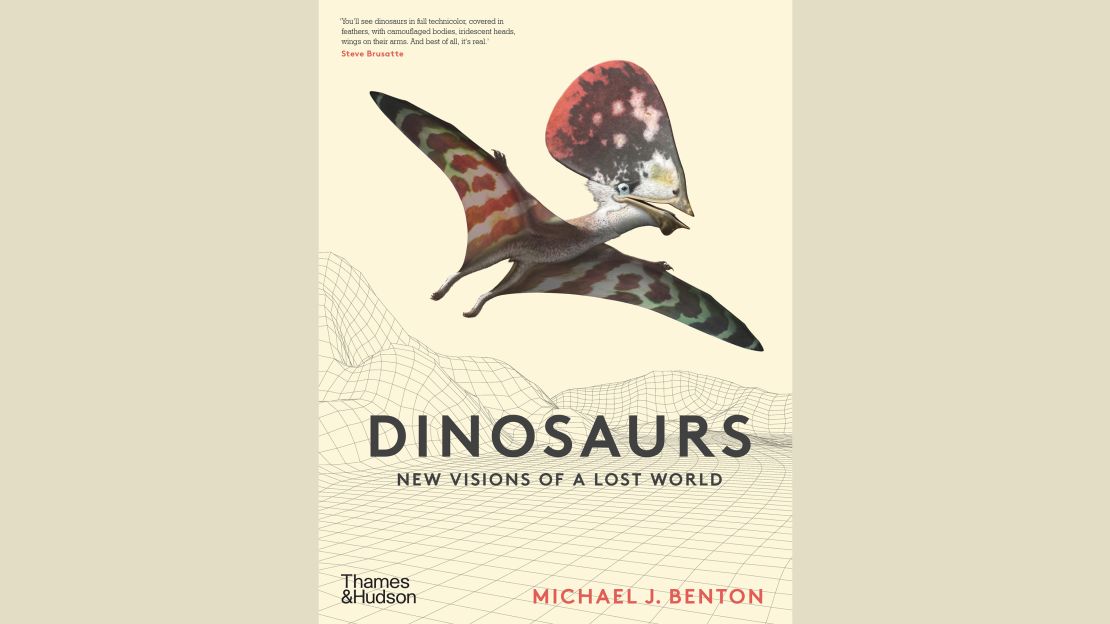

We know today that dinosaurs did not look at all like the scaly versions at Crystal Palace. For decades, however, the sculptures, as well as many other subsequent depictions, inaccurately influenced the public’s view of these extinct giants. Renowned paleontologist Michael Benton’s new book, “Dinosaurs: New Visions of a Lost World,” however, offers the latest interpretation.

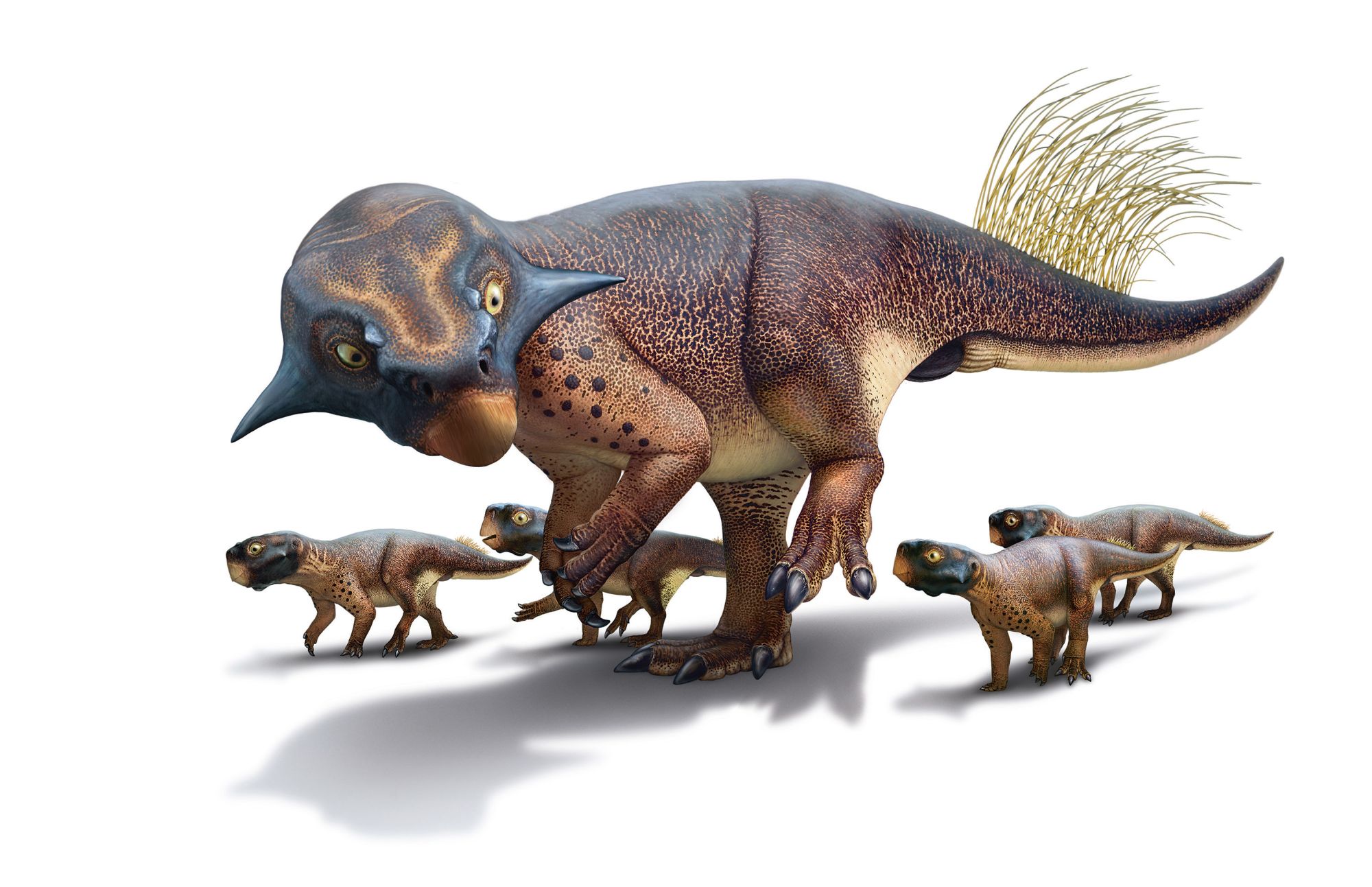

“It’s the first dinosaur book where the dinosaurs actually look like what they looked like,” claims the author, who worked with paleoartist Bob Nicholls to bring the creatures to life. “Every detail, as far as possible, is justified by evidence. We tried to pick species that are quite well documented, so that in the text, I can indicate what we know and why we know it.”

Much of the evidence comes from the most recent fossil discoveries from China, which starting in the 1990s, changed the way we interpret the appearance of dinosaurs. The 1996 discovery in the country’s Liaoning province of a feathered fossil, for example, created a direct connection between dinosaurs and birds.

“I think we can say that feathers originated way earlier than we had thought, at least 100 million years earlier, so right at the root of dinosaurs,” Benton said.

The idea that dinosaurs had feathers hasn’t appealed to everyone. Famously, the “Jurassic Park” franchise – which debuted in 1993 before feathery dinosaurs fossils were first discovered – has steadfastly refused to include them in its most recent films.

“They characterize that by saying they don’t want T-Rex to look like a giant chicken. But it’s a pity,” Benton said.

Even more recently, Benton and his team at the University of Bristol in the UK have pioneered a way, by finding pigment structures embedded deep within the fossilized feathers, to identify the color patterns of a dinosaur from fossils. “We were the first to apply this method in 2010, so the book is documenting mainly studies from the last 10 years that looked at the skin, the scales and the feathers in fossils – to get the color.”

That result is shown through illustrations of 15 creatures featured in the book – not just of dinosaurs but also prehistoric birds, mammals and reptiles – adorned with vibrant skin patterns, an abundance of multicolored feathers and some with striking iridescent heads.

Looking at these creatures shows just how much our knowledge of dinosaurs has improved, and how much it can improve still. “A few years ago, I thought we would have never known about the color of a dinosaur, but now we do,” Benton said.

“Don’t draw boundaries, because sooner or later, a smart young person is going to say, ‘Hey, you guys, we can actually solve this one.’”

“Dinosaurs: New Visions of a Lost World” is published by Thames & Hudson.

Add to queue: Dino-mania

Read: “The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs” (2018)

If you want to know the entire history of the dinosaurs, look no further than this “dinosaur biography” by one of the world’s leading paleontologists, Steve Brusatte. The book chronicles the 200 million-year history of the dinosaurs, from the Triassic, through the Jurassic and into the Cretaceous, when their rule ended via a mass extinction caused by a comet or asteroid. Narrated like an epic saga that illustrates the modern workings of paleontology, it draws on very recent research.

Watch: “Walking with Dinosaurs” (2000)

This classic documentary series, produced by the venerable BBC Natural History Unit and aired by Discovery in the US, had the distinction of being the most expensive documentary ever made when it launched in 1999. It won three Emmys, spawned two sequels and portrayed dinosaurs in their natural habitats – in true documentary style – using a mix of computer graphics and animatronics. It was cutting edge for its time and still holds plenty of entertainment and educational value, although some of the science is now outdated.

This mix between palaeontology and political drama is woven throughout the story of Sue, the largest and most complete T. rex skeleton ever found. After being unearthed in South Dakota in 1990, the fossil became the center of a years-long legal battle over its ownership, illustrating the rifts that can arise between palaeontologists, fossil collectors and governments that own the land on which the fossils are found. Spoiler alert: Sue is now on display at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History.

Listen: “I know Dino” (2016-ongoing)

The go-to podcast for dinosaur lovers, “I Know Dino” is run by Garret Kruger and Sabrina Ricci, a husband-and-wife team of dino enthusiasts. Each hour-long episode focuses on one species, which is discussed and explored in detail with the help of guests. The podcast, which began in 2016, is now approaching 400 episodes.

This Steven Spielberg classic is still the popular culture reference point for dinosaurs. It was the first film to portray them as smart, dynamic and fast-moving creatures. (Who could forget the famous scene with T. rex fighting Velociraptors?) Though it was made nearly 30 years ago, the film’s CGI still holds up to scrutiny. Scientific accuracy has waned over the years, but it’s still an entertaining film to watch, with milestone performances from Laura Dern, Sam Neill and Jeff Goldblum.

Top Image: Reconstruction of a Psittacosaurus, an illustration that appears in the book “Dinosaurs: New Visions of a Lost World.” One fossil find for this creature contained preserved soft tissue, including skin and an array of reed-like feathers on top of the tail.