Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Up a rocky cliff face, through a narrow opening, and at the end of a snaking passage lies a painting that archaeologists say is the world’s oldest known example of storytelling in art history.

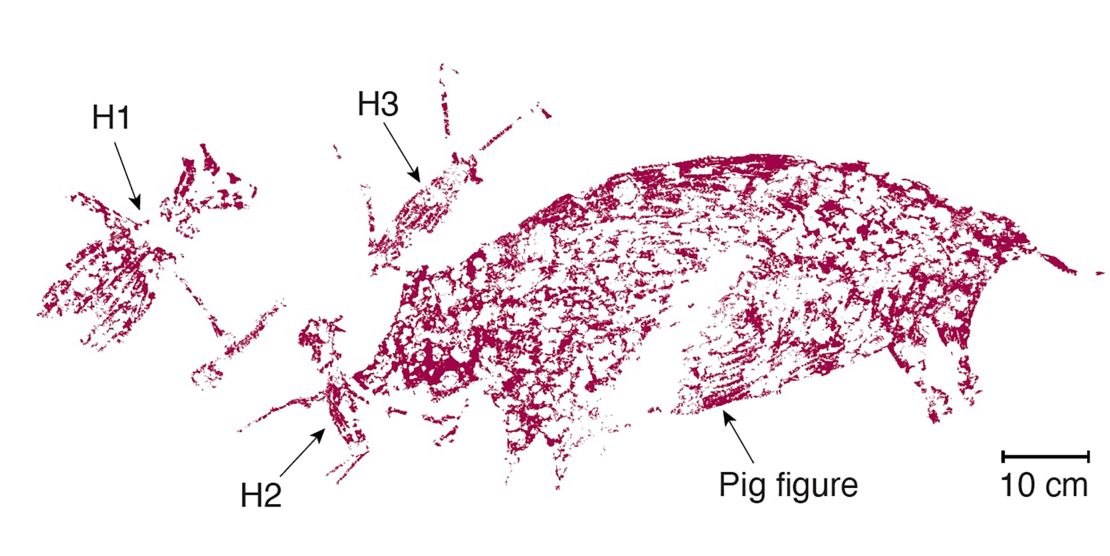

Located inside the limestone cave of Leang Karampuang in the Maros Pangkep region of South Sulawesi, the picture portrays three humanlike figures interacting with a wild pig.

The painting, made with a red pigment, is at least 51,200 years old, according to a study published Wednesday in the scientific journal Nature.

It’s the latest prehistoric art to be found in the area’s intriguing limestone caves. The same study redated a scene of part human, part animal figures hunting warty pigs and dwarf buffaloes, first described in 2019, determining it was at least 48,000 years old. Three warty pigs painted on a cave wall that some of the same researchers reported on in 2021 was previously the world’s oldest depiction of an animal — at 45,500 years old.

The paintings are older than Europe’s famed cave art such as Lascaux in France, and, while younger than some geometric abstract art found in South Africa, it’s the oldest of a narrative scene, the authors of the study said.

“We, as humans, define ourselves as a species that tells stories, and these are the oldest evidence of us doing that,” said study author Maxime Aubert, a professor at Griffith University’s Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research in Australia, via email.

The painter or painters are “conveying more information about images than just individual static images. They are telling us how to look at them in association,” he said.

Adam Brumm, a co-author and professor of archaeology at Australia’s Griffith University, said that he was “shocked and surprised” at the age of the art.

“These narrative artworks seem to have been very important to these early people in Sulawesi,” he said.

The cave art discoveries have challenged a longstanding belief that artistic expression — and the cognitive leap that fired up the human imagination — began in Europe. In doing so, the cave paintings in Indonesia are shedding new light on the early story of humanity.

Evolution of dating techniques

Dating cave art is often difficult if the work is made with mineral pigments such as ocher or manganese rather than biological materials such as carbon.

However, in limestone caves, archaeologists are able to use the radioactive decay of elements such as uranium within the calcium carbonate crusts that form naturally over some parts of an artwork to determine a minimum age.

Renaud Joannes-Boyau, an expert in archaeogeochemistry at Southern Cross University, said the old method for dating cave art involved extracting a sample of the rock and crushing it, combining layers and testing them to determine the minimum age of the art underneath.

However, for this study, he said the team used a very thin laser beam – about half the size of a human hair – to map the individual calcium carbonate layers and determine, with much higher accuracy, the age of the first layer.

The new technique – developed by Joannes-Boyau and Aubert — is less invasive and allows researchers to calculate the age of an artwork from anywhere on the sample cross section, said Aubert, who predicted it would “revolutionize rock art dating worldwide.”

“This is a huge improvement because we can get closer to the pigment layer so the minimum ages can get older but also we can avoid potential issues that can affect the age calculations like possible areas where uranium could have leached out of the sample rendering it too old,” he said.

April Nowell, a Paleolithic archaeologist at the University of Victoria in Canada, whose research focuses on the origins of art, said that she agreed the painted scenes had a narrative quality, which could have been a visual representation of oral stories lost to time.

“My sense is that storytelling has a great antiquity and while we no longer have the oral stories, we have the visual counterparts or visual complements of these stories,” said Nowell, who wasn’t involved in the research.

The study’s dating of the cave art is robust, but it’s “a leap of faith” to suggest that the figurative art was narrative in scope, said Paul Pettitt, a professor of archaeology at Durham University in the United Kingdom.

“It is unclear whether the obvious images were simply isolated depictions that happen to be near others, and also if their supposed spears are natural colourings in the rock or just drawn lines,” he said via email.

Pettitt, who wasn’t involved in the research, said that visual culture might have been common among early modern humans in Africa and elsewhere but perhaps it was done on organic and perishable materials such as tree bark that didn’t withstand the ravages of time.

Aubert said the team believed that these prehistoric Picassos were Homo sapiens, our own species, but other human species could possibly have made the art. Researchers have discovered engravings by Neanderthals in France.

It’s also unclear why so much cave art has been found in this region of Indonesia, Aubert said, but he and his team expected to find more. He said that the finds implied that Homo sapiens had a rich culture of storytelling, using scenic representation to tell visual stories about human-animal relationships.

“We suspect that this art … could date to the first wave of humans that have reached Australia about 65,000 years ago on their migration out of Africa.”

Correction: In a previous version of this story, the headline and photo caption incorrectly stated the number of human figures in the cave art.