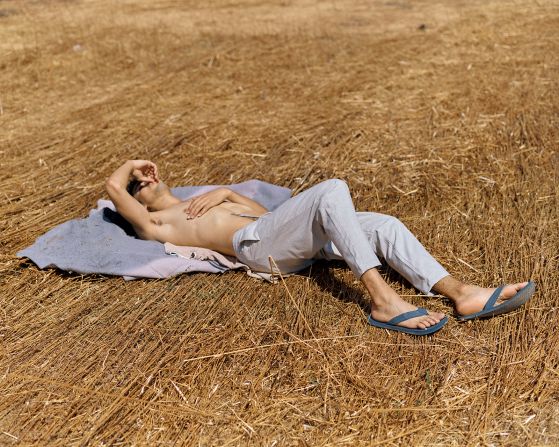

Photographer Felipe Romero Beltrán’s depiction of a migrant facility in Spain oozes with the boredom and malaise of life in legal limbo. His young subjects are seen smoking cigarettes, lifting weights and trimming one another’s hair. Other images show them hanging out in a grubby yard or lying around on mattresses.

The photos were shot with the help of nine young Moroccans whom Beltrán befriended in Seville, capital of the southern region of Andalucía. Published in his new book “Dialect,” the pictures were initially intended to be personal, not political. But they ultimately spoke to what Beltrán called a “Kafka-esque” system in which the men waited for years to learn whether their residency applications would be approved.

“At the beginning, it was just about this group of guys,” Beltrán said on a video call from Madrid. “But of course, I realized that I was photographing these really specific political bodies, or political subjects in this bureaucracy.”

Photos show the lives of young migrants in Spain

Last year, nearly 30,000 migrants arrived in Spain by sea, down from a record of over 58,000 in 2018, according to UNHCR data. Of these, most arrived in the Canary Islands or Andalucía, a region separated from Morocco by the Strait of Gibraltar, a stretch of water just 13 kilometers (eight miles) at its narrowest.

The nine men, who didn’t previously know one another, were among those to arrive by boat during the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic in search of a better life. Recounting his journey with an essay in “Dialect,” one of Beltrán’s subjects, Youssef Elhafidi, recalls another terrified teen migrant being forced by smugglers to pilot their boat.

“He did not want to drive, the fear was paralyzing him, they took out a knife and put it on his neck, threatening him to start the engines,” Elhafidi wrote. “The boy started the machine between trembling and crying and we headed north.”

Killing time

According to Beltrán, his nine subjects were required to stay in Spain for three continuous years before applying for residency. Undocumented and without the right to work during this time, they were dependent on the state for food and housing.

While living at the government-run facility, the men took Spanish lessons and joined workshops to help them adapt to life in Spain — some of which were run by Beltrán.

Overcoming an initial language barrier, the photographer began working with the group to produce images and videos. As well as candid portraits, the pictures focus on conditions at the facility, from peeling walls to basic food supplies.

Many of the images were, however, staged. As Beltrán looked for different ways to engage with his subjects, he asked them to re-enact moments from their respective migration journeys. In one, a subject lies motionless on blue gym mats, just as he had upon landing on Spain’s coast. Another shows two of the men carrying a third on their shoulders to recreate the moment he fainted during a day-long walk to Seville from a small town to its south.

The resulting book is thus part documentary and part performance, with Beltrán toeing the line between mentor and collaborator, photographer and choreographer. More than just an artistic decision, staging photos directly responded to the tedium of the migrants’ abundant free time.

“There was an activity around taking the images — it was something during the day that (could get them) excited. And it was fun,” Beltrán recalled. “Everyone was laughing, and they just make jokes each other during the sessions.”

Lost in translation

When Beltrán began delivering workshops at the facility in 2020, he was all too familiar with the system his subjects were trapped in. A few years earlier, he had relocated to Spain from his native Colombia, and — even as a college-educated Spanish speaker — also struggled to navigate the complex immigration processes.

To illustrate the challenge facing his francophone subjects, his project included a video titled “Recital” in which they attempted to read the first four pages of the Spanish immigration law that would determine their futures. “They weren’t understanding a word,” he recalled, noting that, although lawyers were assigned to act on the men’s behalf, the language barrier and dense legalese removed their agency.

The opening pages of “Dialect” — whose title alludes to these very linguistical challenges — are dedicated to stills from the video. Pictures of the men struggling to comprehend the legislation are overlaid with technical terminology (“Right to effective judicial protection” reads the text on one frame; another says, “Authorizations for the purpose of carrying out profit-making activities”).

“These legal procedures are really, really complicated, even for native speakers,” said Beltrán, who is now completing a PhD program in photography in Madrid. “It becomes almost like translation work — translating these laws and bureaucracies into (something understandable to) normal people like us.”

The result, he said, is an inevitable sense of helplessness.

“You can’t talk with anyone,” Beltrán added. “You can’t ask, ‘Who is the law?’ or ‘Who is the state?’ You don’t have anyone to approach. You don’t have any tools to make a living… The system is built to avoid you, or to deny you access to (it).”

Describing the group as “just young people trying to figure out what to do with life,” the photographer hopes his project can humanize migrants’ experiences in a world increasingly desensitized to images of their suffering.

Since Beltrán completed his project, most of his subjects have completed their three-year wait and now formally reside in Spain, he says. He remains in touch with some — including Elhafidi, who he says works in a restaurant and has accompanied him at promotional events for the book’s launch.

In the conclusion of his essay, Elhafidi recalled how he felt when he secured his residency, writing: “It took me three years of searching and putting courage to life, until finally the moment came, after being cold, scared, hungry and the most difficult thing, my mother’s tears… I got it,” he wrote.

“I got the papers. Now after getting it I have another look at life, I finally feel that I have the opportunity to be whoever I want to be.”

“They’re building their lives,” Beltrán said of those, including Elhafidi, who have secured residency. “Fortunately, they now can go back to Morocco to visit and see their families.”

“Dialect,” published by Loose Joints, is available now.