The expiration of a pandemic-era public health restriction that will significantly alter several years of US immigration policy has arrived, threatening chaos as an estimated tens of thousands of migrants mass near the US-Mexico border in anticipation.

Issued during the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, Title 42 allowed authorities to swiftly turn away migrants at the US borders, ostensibly to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus. But that changed late Thursday when the public health emergency and Title 42 lapsed.

Here’s how border crossings could be impacted after the order’s expiration:

Title 8 is back in effect

Title 42 allowed border authorities to swiftly turn away migrants encountered at the US-Mexico border, often depriving migrants of the chance to claim asylum and dramatically cutting down on border processing time. But Title 42 also carried almost no legal consequences for migrants crossing, meaning if they were pushed back, they could try to cross again multiple times.

Now that Title 42 has lifted, the US government is returning to a decades-old section of US code known as Title 8, which Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas has warned would carry “more severe” consequences for migrants found to be entering the country without a legal basis.

The Department of Homeland Security has repeatedly stressed in recent months that migrants apprehended under Title 8 authority may face a swift deportation process, known as “expedited removal” – and a ban on reentry for at least five years. Those who make subsequent attempts to enter the US could face criminal prosecution, DHS has said.

But the processing time for Title 8 can be lengthy, posing a steep challenge for authorities facing a high number of border arrests. By comparison, the processing time under Title 42 hovered around 30 minutes because migrants could be quickly expelled, whereas under Title 8, the process can take over an hour.

Title 8 allows for migrants to seek asylum, which can be a lengthy and drawn out process that begins with what’s called a credible-fear screening by asylum officers before migrants’ cases progress through the immigration court system.

Title 8 has continued to be used alongside Title 42 since the latter’s introduction during the Covid-19 pandemic, with more than 1.15 million people apprehended at the southern border under Title 8 in fiscal year 2022, according to US Customs and Border Protection. More than 1.08 million people were expelled under Title 42 at the southern land border during that same period.

There’s also a new border policy

The administration is also rolling out new, strict policy measures following the lifting of Title 42 that will go into effect this week.

That includes putting into place a new asylum rule that will largely bar migrants who passed through another country from seeking asylum in the US. The rule, proposed earlier this year, will presume migrants are ineligible for asylum in the US if they didn’t first seek refuge in a country they transited through, like Mexico, on the way to the border. Migrants who secure an appointment through the CBP One app will be exempt, according to officials.

If migrants are found ineligible for asylum, they could be removed through the speedy deportation process, known as “expedited removal,” that would bar them from the US for five years.

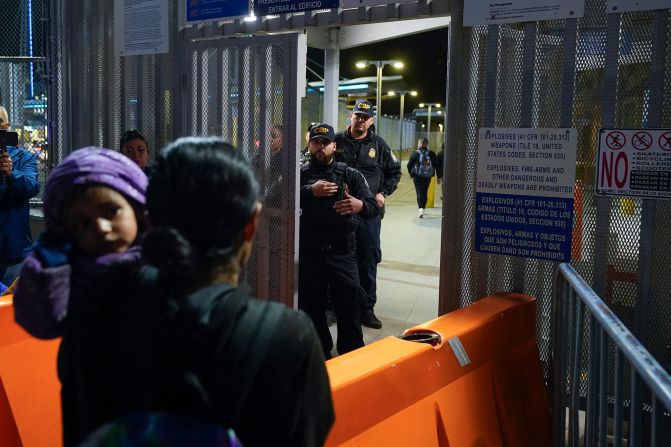

In pictures: The surge at the US-Mexico border

The administration also plans to return Cubans, Venezuelans, Haitians and Nicaraguans to Mexico if they cross the border unlawfully, marking the first time the US has sent non-Mexican nationals back across the border.

The new asylum rule is already facing a legal challenge as the ACLU and other immigrant advocacy groups filed a lawsuit overnight Thursday in an effort to block the policy.

“The Biden administration’s new ban places vulnerable asylum seekers in grave danger and violates U.S. asylum laws. We’ve been down this road before with Trump,” said Katrina Eiland, managing attorney with the ACLU Immigrants’ Rights Project, in a statement. “The asylum bans were cruel and illegal then, and nothing has changed now.”

Senior administration officials have stressed the actions are necessary to encourage people to use lawful pathways to come to the US. That includes parole programs for eligible nationalities to apply to enter the US and expanding access to an app for migrants to make an appointment to present themselves at a port of entry.

The advocates’ lawsuit, filed in federal court in the Northern District of California, cites issues with the CBP One app used for scheduling asylum appointments, including some migrants’ lack of resources to get a smartphone and the absence of adequate internet access to use the app, along with language and literacy barriers.

The State Department plans to open about 100 regional processing centers in the Western hemisphere where migrants can apply to come to the US, though the timeline for those is unclear.

“We have, however, coupled this with a robust set of consequences for noncitizens who, despite having these options available to them, continue to cross unlawfully at the border,” a senior administration official told reporters Tuesday.