Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Multiple space and ground-based telescopes witnessed one of the brightest explosions in space when it reached Earth on October 9. The burst may be one of the most powerful ever recorded by telescopes.

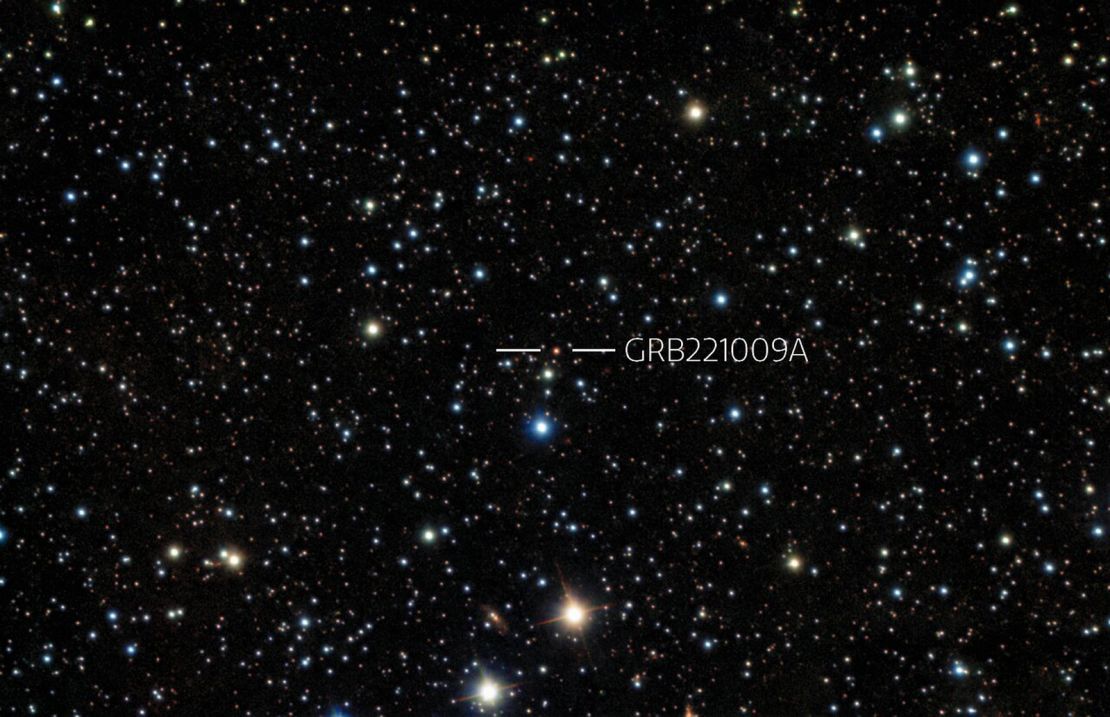

Gamma-ray bursts, or GRBs, are the most powerful class of explosions in the universe, according to NASA. Scientists have dubbed this one GRB 221009A, and telescopes around the world continue to observe its aftermath.

“The exceptionally long GRB 221009A is the brightest GRB ever recorded and its afterglow is smashing all records at all wavelengths,” said Brendan O’Connor, a doctoral student at the University of Maryland and George Washington University in Washington, DC, in a statement.

“Because this burst is so bright and also nearby, we think this is a once-in-a-century opportunity to address some of the most fundamental questions regarding these explosions, from the formation of black holes to tests of dark matter models.”

Scientists believe the creation of the long, bright pulse occurred when a massive star in the Sagitta constellation — about 2.4 billion light-years away — collapsed into a supernova explosion and became a black hole. The star was likely many times the mass of our sun.

Gamma rays and X-rays rippled through the solar system and set off detectors installed on NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory and the Wind spacecraft, as well as ground-based telescopes like the Gemini South telescope in Chile.

Newborn black holes blast out powerful jets of particles that can move at close to the speed of light, releasing radiation in the form of X-rays and gamma rays. Billions of years after traveling across space, the black hole’s detonation finally reached our corner of the universe last week.

Studying an event like this can reveal more details about the collapse of stars, how matter interacts near the speed of light and what conditions may be like in distant galaxies. Astronomers estimate that such a bright a gamma ray burst may not appear again for decades.

The burst’s source sounds distant, but astronomically speaking it’s relatively close to Earth, which is why it was so bright and lasted for so long. The Fermi telescope detected the burst for more than 10 hours.

O’Connor was the leader of a team using the Gemini South telescope in Chile, operated by the National Science Foundation’s National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory, or NOIRLab, to observe the aftermath on October 14.

“In our research group, we’ve been referring to this burst as the ‘BOAT’, or Brightest Of All Time, because when you look at the thousands of bursts gamma-ray telescopes have been detecting since the 1990s, this one stands apart,” said Jillian Rastinejad, a doctoral student at Northwestern University in Illinois who led a second team using Gemini South.

Astronomers will use their observations to analyze the signatures of any heavy elements released by the star’s collapse.

The luminous burst also provided an opportunity for two devices aboard the International Space Station: the NICER (or Neutron star Interior Composition Explorer) X-ray telescope and Japan’s Monitor of All-sky X-ray Image, or MAXI. Combined, the two devices are called the Orbiting High-energy Monitor Alert Network, or OHMAN.

It was the first time the two devices, installed on the space station in April, were able to work together to detect a gamma-ray burst, and meant the NICER telescope was able to observe GRB 221009A three hours after it was detected.

“Future opportunities could result in response times of a few minutes,” said Zaven Arzoumanian, NICER science lead at Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, in a statement.