Editor’s Note: Kent Sepkowitz is a physician and infectious disease expert at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization, suggested last week that we may be approaching the end of the Covid-19 pandemic, providing music to the ears of the world’s almost 8 billion people.

“We have never been in a better position to end the pandemic,” Tedros said Wednesday. “We’re not there yet, but the end is in sight.”

I agree with him. Cases, hospitalizations and deaths in most countries – though not all – are decreasing. In addition, many in the world either have received a vaccine, developed the disease or had both, providing a reasonable hope that we have some amount of herd protection.

But Tedros is right to be cautious. As we near the end of the third pandemic year, the accuracy of most prognostications has been dreadful. The coronavirus always seems to be several steps ahead of our understanding despite our best attempts. Yes, right this moment, we seem to have the upper hand, especially given the absence of a galloping new variant of the virus that causes Covid-19, a break in the action we haven’t experienced in a long while.

Furthermore, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently defined just how much progress has been made, at least against fatal disease. It’s sort of a good news-bad news update. The CDC described three phases in the post-vaccination era: that dominated by the Delta variant (summer 2021), then the “early Omicron” moment (winter 2022) and most recently the “later Omicron” period (spring 2022).

The rate of death for those sick enough to be hospitalized has decreased dramatically: It was about 15% during the Delta variant predominance and steadily has dropped over the last year to less than 3% during the late Omicron phase, according to the CDC. Those figures are good news from the perspective of a trend.

Yet in the United States, hundreds of deaths from the disease continue daily, with 4 out of 5 fatalities in those at least 65 years of age, especially those who have other concurrent medical conditions.

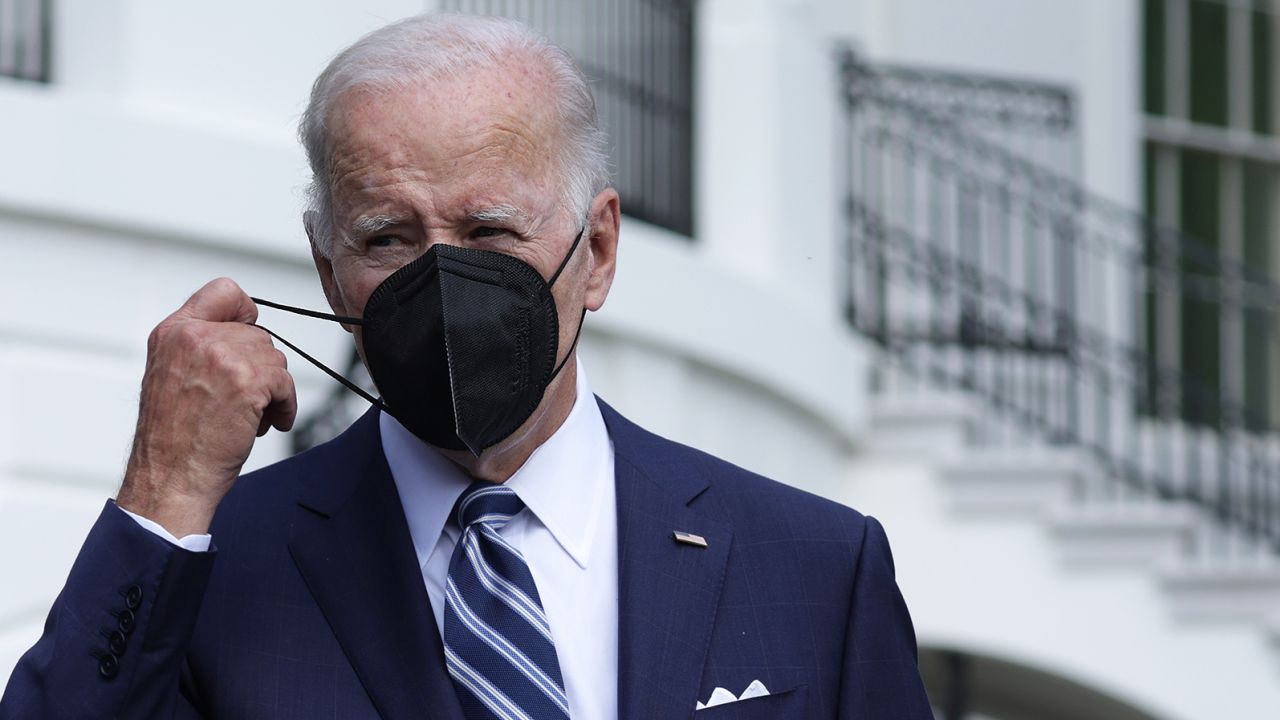

In other words, even if we consider the pandemic “over,” we still are not finished battling Covid-19. As President Joe Biden said during a CBS “60 Minutes” interview, “The pandemic is over. We still have a problem with Covid.”

Given the yes-no moment we are in, I fear that the WHO chief’s pronouncement may cause a celebration that’s still too early. Tedros used the metaphor of a race almost – but not quite – won. For me, this is very much the wrong way to think about what’s ahead. It’s not a race or war; there is no medal to drape over a bowed head or a belligerent to step forward in surrender.

Rather the enemy is an anarchic scrap of RNA that goes from here to there without cause or concern, direction or purpose. We are seeking a relatively peaceful cohabitation with the virus given that an out-and-out victory is beyond reach. Not only will there be no bang, but there will be no whimper, just a change of pace and intensity that periodically will remind us that a full-scale new wave could be just around the bend.

So how do we know when the pandemic is over? The WHO actually does have a formal way of determining the start and end of any pandemic, which it refers to as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, or PHEIC. Besides Covid-19, it has done so six other times since 2007 (for influenza, polio, twice for Ebola, Zika and monkeypox). National public health groups such as the CDC defer to the WHO’s judgment.

An 18-member committee of experts constituted by the WHO make these decisions. This group has relatively clear criteria to use when deciding to declare a public health emergency: The problem must be “serious, sudden, unusual or unexpected,” likely to spread globally and likely to require immediate international action, according to Science magazine.

However, criteria for declaring the end of a pandemic are less clear. Some hard-edged data, such as declining case numbers or rising vaccine rates, can help, but the final decision is based more on social and political rather than scientific grounds, Caroline Buckee, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, told Science. “There’s not going to be a scientific threshold,” she said. “There’s going to be an opinion-based consensus.”

This reversion to hand-to-hand decision-making initially may seem a disappointment. After all, we have muscled our way out of calamity by using high-end scientific techniques, mastering how to introduce messenger RNA into a human cell with a confidence that would have made the great science fiction writer Ray Bradbury wince. So, too, with antibody treatments, antivirals and rapid at-home tests.

So why are we relying on head-scratching experts sitting around a table to advise us on the symbolic end of the pandemic, as if we can then resume normal-ish life? Are human minds sophisticated enough to make important decisions for a disease that has left more than 6.5 million dead worldwide and has fooled the best experts every step of the way?

Get our free weekly newsletter

- Sign up for CNN Opinion’s newsletter.

- Join us on Twitter and Facebook

There never was going to be a way to see into the future more than a day or two, given a new pathogen doing unexpected things in a completely non-immune population. So, too, with its end. So yes, the 18 experts will gather and think and then worry and think some more. Eventually, they will give an all-clear.

For the pandemic that is. The pandemic, however, is not synonymous with Covid-19. The risk of catching a bad case of the virus called SARS-CoV-2 will remain with us for the foreseeable future. And how well we handle its quieter version will determine just how long we remain pandemic-free.