Up for a little noninvasive brain stimulation to boost your aging memory for that next big project, work meeting or family get-together? One day science may be able to offer such treatments, new research suggests.

Sending electrical currents into two parts of the brain known for storing and recalling information modestly boosted immediate recall of words in people over 65, according to astudy by a team at Boston University published Monday in Nature Neuroscience.

“Whether, these improvements would occur for everyday memories, rather than just for lists of words, remains to be tested,” said Masud Husain, a professor of neurology and cognitive neuroscience at the University of Oxford, in a statement. He was not involved in the study.

Still, the study “provides important evidence that stimulating the brain with small amounts of electrical current is safe and can also improve memory,” said Dr. Richard Isaacson, director of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic in the Center for Brain Health at Florida Atlantic University’s Schmidt College of Medicine, who was not involved in the research.

Improvements were most pronounced in people in the study with the poorest memories, who “would be considered to have mild cognitive impairment,” said neuroscientist Rudy Tanzi, a professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, who was not involved with the study.

“There was an apparently beneficial effect on immediate word recall in those with mild cognitive impairment,” said Tanzi, who is also director of the genetics and aging research unit at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“This preliminary but promising finding warrants more exploration of the use of bioelectronic approaches for disorders like Alzheimer’s disease,” he added.

Boosting brain change

Scientists used to think that by a certain point in early adulthood the brain was fixed, unable to grow or change. Today, it’s widely understood that the brain is capable of plasticity – the ability to reorganize its structure, functions or connections – throughout life.

Transcranial alternating current stimulation, or tACS, attempts to enhance the brain’s functionality with a device that applies wavelikeelectrical currents to specific areas of the brain through electrodes on the scalp. The electrical waves can mimic or change brainwave activity to stimulate growth and hopefully change the brain’s neural networking.

An alternate version that uses magnetic fields, called transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS, is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat depression.

“I believe this is the future of neurologic intervention, to help strengthen networks in our brains that may be failing,” said Dr. Gayatri Devi, a clinical professor of neurology and psychiatry at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell University in New York. She was not involved in the newstudy.

“Additionally, treatment may be tailored to each person, based on that individual’s strengths and weaknesses, something pharmacotherapy is not able to do,” Devi said.

In the new findings published in Nature Neuroscience, brain cells are “activated at specific time points, and that is defined by the frequency of the (electrical) stimulation,” said study coauthor Shrey Grover, a postdoctoral student in the brain, behavior and cognition program at Boston University.

“The consequence of changing the timings at which brain cells activate is that it induces this process of plasticity. The plasticity is what allows the effects to be carried forward in time even when the stimulation has ended,” he added.

Memories fade

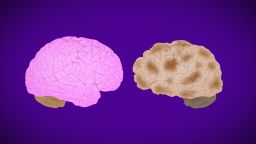

As the brain ages, it’s common to lose some of the ability to remember. For some people it may be short-term memory that suffers the most: Where did I park my car at the mall on this shopping trip? Others may have issues with remembering things over a longer period of time: Where did I park my car two weeks ago before I got on a plane for vacation? And some struggle with both types of memory.

The Boston University researchers analyzed both slightly longer term memory and short-term or working memory separately in two experiments, each with randomized groups of 20 people ages 65 to 88. The experiments alternated between applying gamma waves at 60 hertz and theta waves at 4 hertz to two brain centers that play key roles in memory.

Gamma waves are the shortest and fastest of the brainwave frequencies, operating between 30 and 80 hertz, or cycles per second. Some brain waves referred to as high-gammahave been clocked up to 100 hertz.

A brain on gamma waves is intensely and fully engaged. People under stress who need to be laser-focused – such as when they’re taking a test, solving a complex problem or fixing a difficult mechanical issue – may produce gamma waves.

Theta waves are much slower, ranging between four and eight cycles a second. You are probably running on auto-pilot when you’re in theta mode – driving to work without thinking about the route, brushing your teeth or hair, even daydreaming. This is often when people mull over an idea or come up with a solution to a problem. Studies have found that theta activity can predict learning success.

Targeting memory areas of the brain

In the first experiment, one group received high-frequency (60 hertz) gamma waves to their prefrontal cortex, which sits directly behind the eyes and the forehead. As the center of learning and cognition, the prefrontal lobe assists in storing long-term memories.

A different group of 20 people received low-frequency (4 hertz) theta stimulation to the parietal cortex, an area of the brain located just below where a ponytail would sit. The parietal cortex is above the hippocampus, another part of the brain that plays a major role in learning and memory. People with Alzheimer’s often have a shriveled hippocampus as the organ loses tissue and shrinks.

A third set of 20 people underwent a sham process to serve as a control group.

Sessions occurred over four consecutive days. Each person took five 20-word recall tests during the daily 20-minute stimulation. They were asked to immediately recall as many words as they could at the end of each of the five tests.

The research team evaluated performance in two ways: How well did participants remember words from the end of list, which they would have just heard? That would be the measure of short-term or working memory. How many words could they recall from the beginning of each list, which would have been minutes in the past? That result would assessthe ability to remember for a somewhat longer period of time.

Results showed 17 of the 20 people who received high-frequency gamma stimulation improved in their ability to recall words from the beginning of the word test – what the researcherscalled longer-term memory.

Similarly, 18 of the 20 participants who underwent lower-frequency theta stimulation improved their short-term working memory, or their ability to recall thewords heard last.

Compared with the group of people receiving the sham or placebo stimulation, those who received the treatments saw results that “translates to the older individuals recalling, on average, four to six words more out of the list of 20 words by the end of the 4-day intervention,” said study coauthor Robert Reinhart, director of the Cognitive & Clinical Neuroscience Laboratory at BostonUniversity.

“It is important to emphasize that the study mainly shows modest but significant improvement in short-term memory, but does not show clear effects on long-term memory since the test was based on word recall only a minute or so after learning the words,” Tanzi said.

“Cognitive experts would say what you recall from an hour ago is long-term memory,” Tanzi added. “But with regard to Alzheimer’s clinical symptoms and age-related memory impairment, we would group this into short-term memory. When we say Alzheimer’s patients retain long-term memory, we are referring to recalling details of their wedding day.”

Personalized treatment

Flipping the areas of the brain that received the theta and gamma stimulation in a second experiment produced no benefits, the study found. A third experiment with 30 people was done to verify previous results.

One month after the intervention, participants were asked to do another word recall test to see whether the memory improvements lasted.

Overall, the results showed low-frequency theta currents improved short-term working memory at one month while higher frequency gamma stimulation did not. The opposite was true for the longer-term memories – gamma, but not theta, improved performance.

“Based on the spatial location and the frequency of the electrical stimulation, we can improve either short-term memory or long-term memory separately,” explained Reinhart, an assistant professor in Boston University’s department of psychological and brain sciences.

This means researchers can tailor the treatment to a person’s needs, Reinhart said.

What would that be like? The devices are well tolerated, with limited to no side effects.

“In an ideal world, a portable at-home device that could offer this therapy would be the eventual goal,” said Isaacson, a trustee for the McKnight Brain Research Foundation, which funds research on the aging brain.

“For now, it’s cumbersome to receive these treatments, as specialized equipment is needed. It can also be time-intensive and costly as well,” Isaacson added. “Still, there are limited treatment options for cognitive aging, which affects tens of millions of people, so this is a hopeful step forward to address symptoms and improve brain health.”