Social stress such as discrimination and family problems, along with job and money problems, can contribute to premature aging of your immune system, a recent study found. That’s a double whammy, as the immune system already deteriorates with age.

Immune aging can lead to cancer, heart disease and other age-related health conditions and reduce the effectiveness of vaccines, such as Covid-19, said lead author Eric Klopack, a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Southern California’s Leonard Davis School of Gerontology.

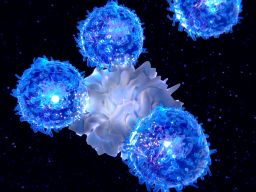

“People with higher stress scores had older-seeming immune profiles, with lower percentages of fresh disease fighters and higher percentages of worn-out T-cells,” Klopack said.

T-cells are some of the body’s most important defenders, carrying out several key functions. “Killer” T cells can directly eliminate virus-infected and cancer cells, and help clear out so-called “zombie cells,” senescent cells that no longer divide but refuse to die.

Senescent cells are trouble because they release a variety of proteins that affect the tissues around them. Such cells have been shown to contribute to chronic inflammation. As more and more build up in the body, they promote conditions of aging, such as osteoporosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and Alzheimer’s disease.

In addition to finding that people who reported higher stress levels had more zombie cells, Klopack and his team found they also had fewer “naive” T cells, which are the young, fresh cells needed to take on new invaders.

“This paper adds to findings that psychological stress on one hand, and well-being and resources on the other hand, are associated with immunological aging,” said clinical psychologist Suzanne Segerstrom, who was not involved with the study.

Segerstrom, a professor of developmental, social and health psychology at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, has studied the connection between self-regulation, stress and immune function.

“In one of our newer studies … older people with more psychological resources had ‘younger’ T cells,” Segerstrom said.

Poor health behaviors

Klopack’s study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, analyzed blood biomarkers of 5,744 adults over the age of 50 collected as part of the Health and Retirement Study, a long-term national study of economic, health, marital and family stresses in older Americans.

People in the study were asked questions about their levels of social stress, which included “stressful life events, chronic stress, everyday discrimination and lifetime discrimination,” Klopack said. Their responses were then compared with levels of T-cells found in their blood tests.

“It’s the first time detailed information about immune cells has been collected in a large national survey,” Klopack said. “We found older adults with low proportions of naive cells and high proportions of older T cells have a more aged immune system.”

The study found the association between stressful life events and fewer naive T cells remained strong even after controlling for education, smoking, drinking, weight and race or ethnicity, Klopack said.

However, when poor diet and a lack of exercise were taken in account, some of the connection between social stress levels and an aging immune system disappeared.

That finding indicates that how much our immune system ages when we are stressed is under our control, Klopack said.

How stress affects the brain

As stress hormones flood the body, neural circuitry in the brain changes, affecting our ability to think and make decisions, experts say. Anxiety rises and mood may change. All of these neurological changes impact the whole body, including our autonomic, metabolic and immune systems.

“The most common stressors are ones that operate chronically, often at a low level, and that cause us to behave in certain ways. For example, being “stressed out” may cause us to be anxious and or depressed, to lose sleep at night, to eat comfort foods and take in more calories than our bodies need, and to smoke or drink alcohol excessively,” wrote renowned neuroendocrinologist Bruce McEwen in a 2017 review of the impact of stress on the brain.

McEwen, who made the landmark 1968 discovery that the brain’s hippocampus can be changed by stress hormones like cortisol, passed away in 2020 after 54 years of researching neuroendocrinology at The Rockefeller University in New York City.

“Being ‘stressed out’ may also cause us to neglect seeing friends, or to take time off from our work, or reduce our engagement in regular physical activity as we, for example, sit at a computer and try to get out from under the burden of too much to do,” McEwen wrote.

What to do

There are ways to stop stress in its tracks. Deep breathing ramps up our parasympathetic nervous system, the opposite of the“flight or fight” response. Filling the belly with air to the count of six will ensure you are breathing deeply. Moving your body as if it is in slow motion is another way to trigger that calming reflex, experts say.

Interrupt your stressful, anxious thinking with cognitive behavioral therapy or CBT. It has been shown in randomized clinical trials to ease depression, anxiety, obsessive thinking, eating and sleep disorders, substance abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder and more. This practicetends to focus more on the present than the past, and is typically a shorter-term treatment, experts say.

Want more tips? Sign up for CNN’s newsletter series: Stress, But Better.