The first time Justin Salinger and his wife experienced a miscarriage was one of the worst days of their lives together.

The Santa Rosa, California, couple had spent months imagining what and who their baby would become. In an instant, those hopes and dreams were gone. They wept. They cursed fate. They wondered again and again: Why us? Why our child?

Friends and family members showed up to support them in their time of need. They cooked meals. They brought flowers. It was an outpouring of empathy like nothing either of them had ever seen. Yet about halfway through the grieving process, Salinger noticed something peculiar: While everyone wondered how his wife was doing, very few loved ones asked about him.

In that moment of sorrow, Salinger, 36, felt totally alone.

“When you have a miscarriage, there’s this idea that it’s not as real for the man because we’re not growing the baby inside of us,” said Salinger, who, along with his wife, has lost six pregnancies. “We’re conditioned not to express emotion and to give our wives space to feel grief and pain. The truth is that we’re hurting, too.”

It turns out Salinger isn’t the only man to experience this sort of isolation after a miscarriage; anecdotally, many men catch the same vibe.

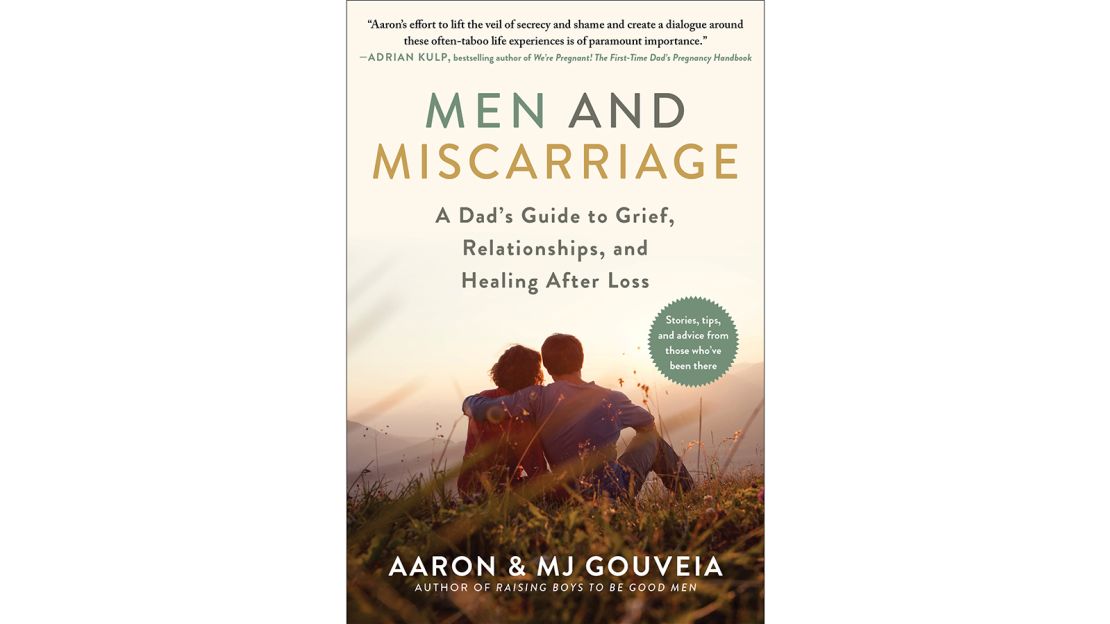

This phenomenon is the subject of a new book that hit bookshelves July 6.

The book, titled, “Men and Miscarriage: A Dad’s Guide to Grief, Relationships, and Healing After Loss,” was written by married partners who have become accidental experts in childbirth tragedy. Over the course of their 15-year marriage, authors Aaron and MJ Gouveia have weathered four miscarriages and a medically necessary abortion. Both husband and wife experienced monumental losses. Until recently, Aaron’s remained unaddressed.

“I say this unequivocally: The person carrying the pregnancy has a tougher time with miscarriage because it’s happening to their bodies,” Aaron Gouveia said. “That doesn’t mean there’s not room to talk about men and non-carrying partners in this scenario. We need to move out of the shadows.”

Understanding a phenomenon

Whichever partner gets the spotlight, no conversation about miscarriage can begin without establishing some foundational truths about what it is and how often it happens.

Any spontaneous and unexpected loss of pregnancy before the 20th week is considered a miscarriage. Researchers say “miscarriage” is somewhat of a loaded term, since some of them occur because a fetus isn’t developing normally, and the body overcorrects by terminating the pregnancy.

The truth: Researchers still really don’t know why miscarriages happen.

What scientists do know: About 10% to 20% of known pregnancies end in miscarriage, at least according to the Mayo Clinic. Many obstetricians and other experts say this number likely is even higher, since many miscarriages occur so early in a woman’s pregnancy that some women don’t realize they are pregnant at all.

Typically, because women are the ones carrying the fetus, miscarriages are perceived to be biopsychosocial in nature — that is, they affect moms biologically, psychologically and socially.

But fathers experience acute loss as well, said Kate Kripke, founder and director of the Postpartum Wellness Center in Boulder, Colorado. Theirs is psychosocial, without the biology.

“When you think about the progression of conversations and research around all of the pregnancy related-challenges families face, it’s somewhat remarkable that the dialog still excludes the male perspective,” said Kripke, a licensed clinical social worker. “I would go so far to say that fathers are left out of the conversation entirely.”

Kripke cited toxic masculinity and age-old gender stereotypes as two driving factors behind this phenomenon — the expectation that men must be stoic, that stoicism equals strength, and that expressing emotions therefore is some sort of weakness, particularly during a time of tumult or unexpected turmoil.

She added that most men express grief and depression differently than women, typically by immersing themselves in distracting behaviors instead of seeking connection.

For this reason, it’s important to make space for completely different emotions from each partner.

“There’s this context in psychotherapy that amounts to ‘both/and’ and not ‘either/or,’ which means mom and dad are each going to have experiences they share, and experiences that are individual,” Kripke said. “In general, I don’t think we do enough of a good job asking the basic questions, ‘How are you doing?’ or ‘What has it been like for you?’”

Growing support

The Gouveias’ book works to change this approach. Sharing their own experiences and incorporating a variety of interviews of other parents who have experienced miscarriage, the couple examines the shame and stigma associated with pregnancies that don’t go as planned.

The work also seeks to understand more about why men don’t seek more opportunities to express their feelings during these seasons of grief.

The reason no one hears much about how men are impacted by miscarriage, the authors say, is because hardly anyone has ever bothered to ask them about it.

In a July interview from their home in Franklin, Massachusetts, Aaron Gouveia said he was “totally screwed up” by the miscarriages and losses he and his wife experienced, and that they left him in a “huge state” of uncertainty.

“I literally didn’t know how to deal with it,” he said. “I didn’t know if I was allowed to grieve. I didn’t know what grieving looked like. I didn’t know if it even mattered, since I was just the dad. And I was worried that if I talked about it with anyone — MJ or anyone — I would be a burden. So I did what most men do in this situation. I soldiered on. Which was exactly not the thing to do.”

Chris Whitfield went through similar paces late this year when he and his wife experienced a miscarriage — the first for either of them.

Looking back, Whitfield said he “didn’t know what to feel,” but remembered that his first thought was that he needed to “protect” his wife and daughter from a previous relationship, and by putting all his time into making sure they were OK.

“What was I protecting them from? I don’t know, grief, I guess, even though I knew I couldn’t,” he admitted in a recent email.

Instead of suffering in silence, Whitfield, who lives in Newcastle, England, went online to find out more about what causes miscarriage, what he should expect in the weeks that follow, and what sort of emotional outlets he might consider pursuing. He found lots of information geared toward women. He found almost nothing for men.

Whitfield set up a website to provide this missing information in March. The site shares a title with Gouveia’s book: “Men and Miscarriage.” In three months, the site has received more than 100,000 unique visitors, and has amassed an active user community of more than 1,000 members.

“A lot of the community conversations are all similar stories, guys who have wanted to talk, but never had the platform to do so, and all the stories, are very similar in stature in that the miscarriage happens, the female partner has been offered resources but the offer for guys is slim to none,” said Whitfield, who does not profit from the website, via email. “For me it’s all about raising awareness that men have feelings too.”

What happens next

With an uptick in the number of men openly talking about miscarriage, Whitfield, Gouveia and Salinger hope it becomes easier for those guys who would rather remain silent. All three fathers hope for a world in which no man is ashamed or afraid to discuss the subject.

Scott Schoenfelder agrees.

Schoenfelder is one half of a couple who experienced two miscarriages and one lost pregnancy over the course of eight years. He still struggles to talk about the tragedies, largely because he hasn’t had much of a chance to do so since they occurred. The 44-year-old added that simply talking about the grief and loss makes the heartache more palatable — a sign that more men should get comfortable talking it out.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

“Friends and family are not comfortable bringing it up, which only leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy of those going through it feeling like a total failure,” said Schoenfelder, who recently moved to Denmark from Milwaukee with his wife and four kids.

Ultimately, he added, “feeling all alone keeps you focused on your own experience, and from realizing there are so many other people going through the same thing.”

Matt Villano is a writer and editor in Healdsburg, California.