Editor’s Note: Lisa Selin Davis is the author of “Tomboy: The Surprising History and Future of Girls Who Dare to Be Different.” She has written for The New York Times, CNN, The Wall Street Journal, The Guardian and many other publications.

My 11-year-old daughter and I cracked open a book I’d bought for her on puberty and changing female bodies. On the very first page it informed her that, once her body developed, men would start looking at her differently.

We crinkled our noses in some combination of discomfort and skepticism. No matter how her body changed, we both knew she would continue to wear the same oversize hoodies, cargo pants and short hair dyed pink that she’d been sporting for years. However well intentioned and helpful to gender-typical girls the book’s messages were, they didn’t seem to apply to a kid like mine, who had flouted gender norms her entire life. These books and others like it operate on the assumption that, once puberty hit, girls like mine would feminize and conform.

Gender atypical girls have often been tolerated or even encouraged before puberty. “Historically, they were labeled tomboys and there was a high acceptance of that and a presumption that they’d outgrow it,” said Robert Blum, professor of public health at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and lead investigator of The Global Early Adolescent Study, which looks at how gender socialization affects health globally.

For a book about tomboys, I interviewed dozens of women who’d had happy tomboy childhoods, or what some have called a “boyhood for girls.” (For boys, that kind of gender atypicality was never sanctioned, even in childhood; they were called sissies, or worse.) These girls played baseball or football, hung out with boys and got their hands dirty. Many ran, shirtless, across the fields, until their mothers — they told me it was always their mothers — told them they were getting close to puberty and had to wear their shirts.

Acceptance of their gender nonconforming behavior had an expiration date on it, whether the kids wanted it to or not.

Changing bodies, changing expectations

Puberty changes the rules of gender, and the force of gender norms and stereotypes bear down, even on kids who might have been immune to them before. In addition to the discomfort of a changing body, kids suddenly encounter changing expectations and social norms, based on their body parts.

Gender stereotypes are international, ubiquitous and harmful, and particularly insidious as puberty approaches, noted Blum’s 2017 study, It Begins at 10: How Gender Expectations Shape Early Adolescence Around the World.

“There is a global set of forces from schools, parents, media, and peers themselves that reinforce the hegemonic myths that girls are vulnerable and that boys are strong and independent,” the report noted. Girls also feel pressure to sexualize, and boys feel pressure to see girls as sexual objects, leading to gender-based violence. In addition, puberty starts earlier for girls than it used to, so many girls’ bodies are changing before their minds are ready.

Many kids are “really uncomfortable with the kind of messaging that assigns them certain gender roles, or certain attention paid to their gender,” said Heather Corinna, an educator and founder of Scarleteen, a sex, sexuality and relationship education site for young people.

Kids internalize the pressure to conform, and police those who don’t, Corinna said. So do parents, even unwittingly. Parents treat kids differently based on sex, with separate and unequal rules and expectations, many studies have shown.

The damage that conformity can cause

The problem with those unequal rules and expectations is that they can force kids into boxes that just don’t fit. Boys who feel pressure to conform to male stereotypes may grow into men with anxiety, who drink too much, tamp down their feelings or are prone to violence, according to ethnographer Maria do Mar Pereira, associate professor of sociology at the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom and author of “Doing Gender in the Playground: The Negotiation of Gender in Schools.”

Meanwhile, many girls internalize the pressure to be thin; some 5% of girls suffer from eating disorders and some 60% are on diets. Twice as many girls than boys drop out of competitive sports by age 14, due to lack of role models, social stigma and decreased access, among other reasons, according to the Women’s Sports Foundation. “This constant effort to manage one’s everyday life in line with gender norms produces significant anxiety, insecurity, stress and low self-esteem for both boys and girls, and both for ‘popular’ young people and those who have lower status in school,” Do Mar Pereira’s study concludes.

Identifying the messages, so we can change them

What can we do to protect our kids from these messages and forces? The first thing is for adults and children to realize they’re perpetuating them.

Even in an era when some kids learn there are dozens of options for gender identity, gender norms persist. “There’s a notion that today there’s a lot more flexibility,” Blum said. “There isn’t. Gender norms are very prescriptive. Gender norms are very restrictive. And everyone reinforces those gender norms.”

Girls can be sent home from school for wearing skirts deemed too short, while boys can be given in-school suspension for wearing nail polish.

Parents, Blum said, are often much more focused on restricting their pubertal daughters than their sons. “But boys are at much greater risk for death from violence,” he said. Adults can and should examine how they treat their boys and girls differently, and how much gender norms influence their decisions.

Widening the range of normal in puberty programming

Puberty education can also focus much more on attacking gender norms, much the way education programs for tweens and teens have tackled child abuse or bullying. That means, Blum said, “teaching kids what’s acceptable and unacceptable behavior.”

What’s acceptable? According to Blum and Corinna, dressing or looking any way you want, no matter your sex or gender identity. What’s unacceptable? Bullying someone because he, she or they don’t look or behave how someone else thinks they should because of their sex. (The use of they/them pronouns are used when referring to an individual who self-identifies as nonbinary, the term that describes a person whose gender identity is neither male nor female.) Parents can tell kids that they don’t need to meet adult expectations of their appearance or behavior just because their bodies are changing.

The programming should also be trans-inclusive, and with the understanding that puberty is hard no matter how you identify or who you are, Corinna said. Some kids, for instance, won’t know they’re intersex until puberty, when their bodies don’t perform as expected, based on the sex they were assigned at birth.

If a child is uncomfortable with the idea or experience of puberty, Corinna said, ask why. Most education around puberty doesn’t adequately address kids’ experiences, they said.

“There’s dismissive messaging to everybody,” Corinna said. “Kids presumed to be cisgender — who may or may not be trans or otherwise gender nonconforming — are often told that any discomfort with puberty must be about them being trans.” The idea that such kids could be uncomfortable with puberty otherwise, Corinna said, is often not even considered. Cisgender refers to children whose gender identity conforms with the sex they were assigned at birth.”

Fighting stereotypes within families and communities

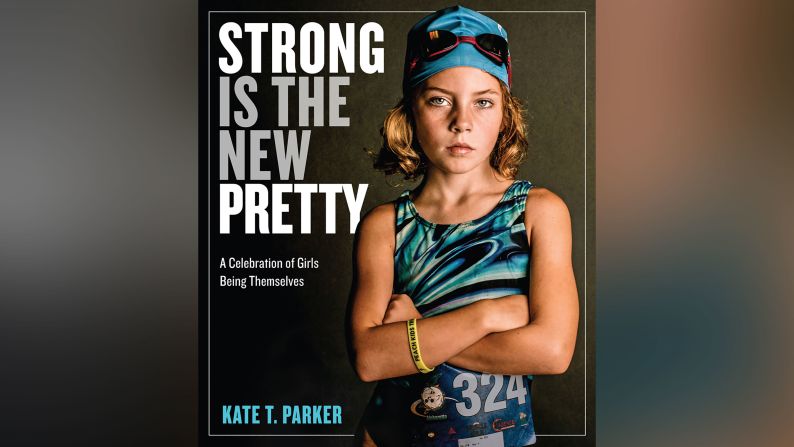

In addition to recognizing how adults treat kids, and improving the kinds of health education they receive, families can present kids with gender-diverse books and media, which have not only trans and nonbinary characters, but also physically and emotionally strong girls and vulnerable, sensitive boys (admittedly, harder to find).

“This is an opportune time for communities to encourage the development of positive health and equitable gender norms early in life that can be transformative both immediately and over the life course,” a 2017 commentary in the Journal of Adolescent Health noted.

In other words, it’s incredibly important to widen the range of what’s acceptable in early adolescence, a time when society is often narrowing that range. “The goal should be to broaden what it means to be conforming,” Blum said.

In the 1970s and early ’80s, many kids listened religiously to “Free to Be… You and Me,” an album encouraging the blasting of gender stereotypes, and telling girls they didn’t have to be traditionally feminine and telling boys they could. “I might be pretty; you might grow tall. But we don’t have to change at all,” go the lyrics of “When We Grow Up,” sung by Diana Ross.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

My parents taught me to question why there were different rules of decorum for boys and girls, and I try to pass on those same critical thinking skills to my kids. I tell my child that all the options are open to her, including the option that, as the song says, she doesn’t have to change at all.

“Our job is to create a protective environment for kids to be who they will become,” Blum said. “And to run interference around those who will try to knock them down because of it.”

Clarification: An earlier version of this story contained a paraphrase of a quote by Heather Corinna that has been replaced with a longer version of the quote.