This artist's illustration shows a young Purussaurus attacking a ground sloth in Amazonia 13 million years ago.

This bundle of bones is the torso of another marine reptile inside the stomach of a fossilized ichthyosaur from 240 million years ago.

Researchers uncovered the fossilized fragments of 200,000-year-old grass bedding in South Africa's Border Cave.

Meet Sasha, the preserved and reconstructed remains of a baby woolly rhinoceros named that was discovered in Siberia.

Stone tools made from limestone have helped researchers to suggest that humans arrived in North America as early as 30,000 years ago.

This image shows both sides of the 1.4 million-year-old bone handaxe made from the femur of a hippopotamus. It was most likely crafted by ancient human ancestors like Homo erectus.

This illustration shows Kongonaphon kely, a newly described reptile that was an early ancestor of dinosaurs and pterosaurs. The fossil was found in Madagascar. It lived about 237 million years ago.

The Okavango Delta in Botswana showcases a patchy landscape where the ability to plan results in a huge survival payoff.

This is a clutch of fossilized Protoceratops eggs and embryos, discovered in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia. They provide evidence that dinosaurs laid soft-shell eggs.

These tools, made from the bones and teeth of monkeys and smaller mammals, were recovered from Fa-Hien Lena cave in Sri Lanka. The sharp tips served as arrow points.

This labeled map shows the complete ancient Roman city of Falerii Novi as it currently exists underground.

Fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls found in the 1950s are seen here.

This is one of the 408 human footprints preserved at the Engare Sero site in Tanzania. The fossilized footprints reveal a group of 17 people that traveled together, likely including 14 women, two men and one juvenile male.

Blade-like stone tools and beads found in Bulgaria's Bacho Kiro cave provide the earliest evidence for modern humans in Europe 47,000 years ago.

This artist's illustration shows what an early, small ichthyosaur that lived 248 million years ago may have looked like. It resembled a cross between a tadpole and a seal, grew to be one foot long and had pebble-like teeth that it likely used to eat invertebrates like snails and bivalves.

This is an artist's illustration of Adalatherium hui, an early mammal that lived on Madagascar 66 million years ago.

This is an artist's illustration showing a cross-section of Earth's forming crust approximately 3 to 4 billion years ago.

Illuminated medieval manuscripts are full of intricate decorations, illustrations and colors, including "endangered colors" that can no longer be recreated today.

These monkeys can be found in ancient Grecian frescoes. And the details are so accurate that researchers were able to identify them as vervet monkeys and baboons.

Archeologists have found the oldest string of yarn at a prehistoric site in southern France. This photograph, taken by digital microscopy, shows that of the cord fragment, which is approximately 6.2 mm long and 0.5 mm wide.

This illustration shows Elessaurus gondwanoccidens, a long-legged reptile that lived in South America during the Early Triassic Period. It's a cousin to other mysterious early reptiles that arose after the Permian mass extinction event 250 million years ago.

The skeletal remains of Homo antecessor are on display in this image. A recent study suggests antecessor is a sister lineage to Homo erectus, a common ancestor of modern humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans.

A nearly two-million-year-old Homo erectus skullcap was found in South Africa. This is the first fossil of erectus to be found in southern Africa, which places it in the area at the same time as other ancient human ancestors.

This painting shows what Antarctica may have looked like 90 million years ago. It had a temperate swampy rainforest.

This artist's illustration of Dineobellator notohesperus shows them in an open landscape, across what is now New Mexico, along with Ojoceratops and Alamosaurus in the background.

Ikaria wariootia was a worm-like creature that lived 555 million years ago. It represents the oldest ancestor on the family tree for most animals.

This is the 3.67-million-year-old 'Little Foot' skull. The view from the bottom (right) shows the original position of the first cervical vertebra, which tells us about her head movements and blood flow to the brain.

This is an artist's illustration of the world's oldest modern bird, Asteriornis maastrichtensis, in its original environment. Parts of Belgium were covered by a shallow sea, and conditions were similar to modern tropical beaches like The Bahamas 66.7 million years ago.

This donkey skull was recovered in a Tang Dynasty noblewoman's tomb. The researchers determined that she played donkey polo and was buried with her donkeys so that she may continue her favorite sport in the afterlife.

Hundreds of mammoth bones found at a site in Russia were once used by hunter-gatherers to build a massive structure 25,000 years ago.

A fossil of an ancient rudist clam called Torreites sanchezi revealed that Earth's days lasted 23.5 hours 70 million years ago.

This is an artist's impression of dinosaurs on prehistoric mudflat in Scotland, based on varied dinosaur footprints recovered on the Isle of Skye.

A new study suggests that ostrich eggshell beads have been used to cement relationships in Africa for more than 30,000 years.

This rock lined the seafloor roughly 3.2 billion years ago, providing evidence that Earth may have been a 'waterworld' in its ancient past.

These stone tools were found at the Dhaba site in India, showing that Homo sapiens survived a massive volcanic eruption 74,000 years ago.

The remains of 48 people who were buried in a 14th century Black Death mass grave were found in England's Lincolnshire countryside.

The articulated remains of a Neanderthal have been found in Shanidar Cave, representing the first discovery of its kind in 20 years.

A rare disease that still affects humans today has been found in the fossilized vertabra of a duck-billed dinosaur that roamed the Earth at least 66 million years ago.

Venezuelan Palaeontologist Rodolfo S├Īnchez is shown next to a male carapace of the giant turtle Stupendemys geographicus, for scale.

This artist's illustration shows the newly discovered Tyrannosaurus rex relative, Thanatotheristes degrootorum.

The newly discovered species Allosaurus jimmadseni represents the earliest Allosaurus known. It was a fearsome predator that lived during the Late Jurassic Period millions of years before Tyrannosaurus rex.

Remains found in ancient Herculaneum boat houses revealed that people trying to flee the eruption of Mount Vesuvius slowly suffocated as volcanic clouds overtook the town.

The Wulong bohaiensis fossil found in China's Jehol Province shows some early, intriguing aspects that relate to both birds and dinosaurs.

Shell tools were recovered from an Italian cave that show Neanderthals combed beaches and dove in the ocean to retrieve a specific type of clam shell to use as tools.

A closer look at the Heslington brain, which is considered to be Britain's oldest brain and belonged to a man who lived 2,600 years ago. Amazingly, the soft tissue was not artificially preserved.

Researchers from Russia's RAS Institute of Archeology excavated the burial sites of four women, who were buried with battle equipment in southwestern Russia and believed to be Amazon warrior women. The oldest woman found in the graves bore a unique, rare ceremonial headdress.

Teen Tyrannosaurus rex were fleet-footed with knife-like teeth, serving as mid-sized carnivores before they grew into giant bone-crushing adults.

A Homo erectus skull cap discovered in Central Java, Indonesia reveals how long they lived and when the first human species to walk upright died out.

This is an artistic reconstruction of Lola, a young girl who lived 5,700 years ago.

Part of the scene depicted in the world's oldest cave art, which shows half-animal, half-human hybrids hunting pigs and buffalo.

An ancient Egyptian head cone was first found with the remains of a young woman buried in one of Amarna's graves.

A lice-like insect was trapped in amber crawling and munching on a dinosaur feather.

Newly discovered penguin species Kupoupou stilwelli lived after the dinosaurs went extinct and acts as a missing link between giant extinct penguins and the modern penguins in Antarctica today.

This illustration compares the jaws and teeth of two predatory dinosaurs, Allosaurus (left) and Majungasaurus (right).

This is an artist's illustration of Najash rionegrina in the dunes of the Kokorkom desert that extended across Northern Patagonia during the Late Cretaceous period. The snake is coiled around with its hindlimbs on top of the remains of a jaw bone from a small charcharodontosaurid dinosaur.

University of South Carolina archaelogist Christopher Moore (second from right) and colleagues collect core samples from White Pond near Elgin, South Carolina, to look for evidence of an impact from an asteroid or comet that may have caused the extinction of large ice-age animals such as sabre-tooth cats and giant sloths and mastodons.

Core samples from White Pond near Elgin, South Carolina, show evidence of platinum spikes and soot indicative of an impact from an asteroid or comet.

The Sosnogorsk lagoon as it likely appeared 372 million years ago just before a deadly storm, according to an artist's rendering. The newly discovered tetrapod can be seen in the left side of the image below the surface.

Bronze goods recovered from a river in northern Germany indicate an ancient toolkit of a Bronze Age warrior.

Mold pigs are a newly discovered family, genus and species of microinvertebrates that lived 30 million years ago.

Ferrodraco lentoni was a pterosaur, or "flying lizard," that lived among dinosaurs 96 million years ago. The fossil was found in Australia.

These Late Bronze Age feeding vessels were likely used for infants drinking animal milk.

This is the first depiction of what mysterious ancient humans called Denisovans, a sister group to Neanderthals, looked like. This image shows a young female Denisovan, reconstructed based on DNA methylation maps. The art was created by Maayan Harel.

Researchers found a fossil of one of the oldest bird species in New Zealand. While its descendants were giant seafaring birds, this smaller ancestor likely flew over shorter ranges.

A painting shows the new species of giant salamander called Andrias sligoi, the largest amphibian in the world.

After her discovery in 2013, Victoria's 66-million-year-old, fossilized skeleton was restored bone by bone. She's the second most complete T. rex fossil on record.

An artist's illustration shows how different an ancient "short-faced" kangaroo called Simosthenurus occidentalis looked, as opposed to modern kangaroos. Its skull more closely resembles a koala.

An artist's illustration of Cryodrakon boreas, one of the largest flying animals that ever lived during the Cretaceous period. Although researchers don't know the color of Cryodrakon's plumage, the colors shown here honor Canada, where the fossil was found.

A graphic thermal image of a T. rex with its dorsotemporal fenestra glowing on the skull.

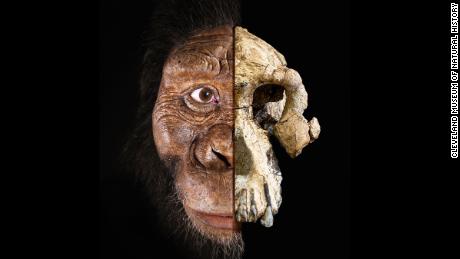

A complete skull belong to an early human ancestor has been recovered in Ethiopia. A composite of the 3.8 million-year-old cranium of Australopithecus anamensis is seen here alongside a facial reconstruction.

The remains inside grave IIIN199, found under Prague Castle in 1928, belong to a man from the 10th century. His identity has been the subject of great debate for years.

Vertebrae fossils of a previously undiscovered type of stegosaurus were found in Morocco. Researchers say they represent the oldest stegosaurus found.

The La Chapelle-aux-Saints Neanderthal skull shows signs of external auditory exostoses, known as "surfer's ear" growths, in the left canal.

The Fincha Habera rock shelter in the Ethiopian Bale Mountains served as a residence for prehistoric hunter-gatherers.

The world's largest parrot, Heracles inexpectatus, lived 19 million years ago in New Zealand. It was over 3 feet tall and weighed more than 15 pounds.

Saber-toothed cats, dire wolves and coyotes had different hunting patterns according to a new study of predator fossils found in the La Brea Tar Pits.

Researchers found 83 tiny glassy spheres inside fossil clams from a Florida quarry. Testing suggests that they are evidence of one or more undocumented meteorite impacts in Florida's distant past.

This primitive dinosaur had a wide W-shaped jaw and a solid bony crest resembling a humped nose.

An illustration of a Microraptor as it swallows a lizard whole during the Cretaceous period. The well-preserved fossils of the Microraptor and the lizard were both found, leading to the discovery that the lizard was a previously unknown species.

The back of a skull found in a Grecian cave has been dated to 210,000 years ago. Known as Apidima 1, right, researchers were able to scan and re-create it (middle and left). The rounded shape of Apidima 1 is a unique feature of modern humans and contrasts sharply with Neanderthals and their ancestors.

A 33,000-year-old human skull shows evidence of being struck with a club-like object. The right side of the man's head has a large depressed fracture.

The recently discovered fossilized femur of an ancient giant bird revealed that it weighed nearly as much as an adult polar bear and could reach 11┬Į feet tall. It lived between 1.5 million and 2 million years ago.

This jawbone belonged to a Neanderthal girl who lived 120,000 years ago. It was found in Scladina Cave in Belgium.

This is an artist's illustration of the newly discovered dinosaur species Fostoria dhimbangunmal.

Radiocarbon dating has revealed that this Iron Age wooden shield was made between 395 and 255 BC.

The incredibly well-preserved fossil of a 3 million-year-old extinct species of field mouse, found in Germany, which was less than 3 inches long, was found to have red pigment in its fur.

A mass grave dated to 5,000 years ago in Poland contains 15 people who were all from the same extended family.

This is an artist's impression of the Ambopteryx longibrachium, one of only two dinosaurs known to have membranous wings. The dinosaur's fossilized remains were found in Liaoning, in northeast China, in 2017.

Reconstruction of a small tyrannosauroid Suskityrannus hazelae from the Late Cretaceous.

Researchers have been studying Archaeopteryx fossils for 150 years, but new X-ray data reveal that the bird-like dinosaur may have been an "active flyer."

A 160,000-year-old Denisovan jawbone found in a cave on the Tibetan Plateau is the first evidence of the presence of this ancient human group outside the Denisova Cave in Siberia.

An artist's illustration of Simbakubwa kutokaafrika, a gigantic carnivore that lived 23 million years ago. It is known from fossils of most of its jaw, portions of its skull and parts of its skeleton. It was a hyaenodont, a now-extinct group of mammalian carnivores, that was larger than a modern-day polar bear.

The right upper teeth of the newly discovered species Homo luzonensis. The teeth are smaller and more simplified than those belonging to other Homo species.

The towering and battle-scarred "Scotty" is the world's largest Tyrannosaurus rex and the largest dinosaur skeleton ever found in Canada.

Researchers discovered unknown species at the Qingjiang fossil site on the bank of the Danshui River, near its junction with the Qingjiang River in Hubei Province, China.

During a study of the ancient Iberian population, the remains of a man and woman buried together at a Spanish Bronze Age site called Castillejo de Bonete showed that the woman was a local and the man's most recent ancestors had come from central Europe.

Durrington Walls is a Late Neolithic henge site in Wiltshire. Pig bones recovered at the site revealed that people and livestock traveled hundreds of miles for feasting and celebration.

An artist's impression of a Galleonosaurus dorisae herd on a riverbank in the Australian-Antarctic rift valley during the Early Cretaceous, 125 million years ago.

The remains of 137 children and 200 llamas were found in Peru in an area that was once part of the Chim├║ state culture, which was at the peak of power during the 15th century. The children and llamas might have been sacrificed due to flooding.

The tooth of an extinct giant ground sloth that lived in Belize 27,000 years ago revealed that the area was arid, rather than the jungle that it is today.

An artist's illustration of what the small tyrannosaur Moros intrepidus would have looked like 96 million years ago. These small predators would eventually become Tyrannosaurus rex.

Examples of tools manufactured from monkey bones and teeth recovered from the Late Pleistocene layers of Fa-Hien Lena Cave in Sri Lanka show that early humans used sophisticated techniques to hunt monkeys and squirrels.

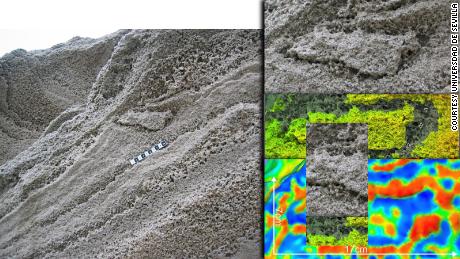

Footprints thought to belong to Neanderthals have been found in the Catalan Bay Sand Dune.

Two of the fossil specimens discovered in Korea had reflective eyes, a feature still apparent under light.

An artist's illustration of Mnyamawamtuka moyowamkia, a long-necked titanosaur from the middle Cretaceous period recently found in Tanzania. Its tail vertebra has a unique heart shape, which contributed to its name. In Swahili, the name translates to "animal of the Mtuka with a heart-shaped tail."

The oldest evidence of mobility is 2.1 billion years old and was found in Gabon. The tubes, discovered in black shale, are filled with pyrite crystals generated by the transformation of biological tissue by bacteria, found in layers of clay minerals.

Researchers recently studied climate change in Greenland as it happened during the time of the Vikings. By using lake sediment cores, they discovered it was actually warmer than previously believed. They studied at several sites, including a 21st-century reproduction of Thjodhild's church on Erik the Red's estate, known as Brattahl├Ł├░, in present day Qassiarsuk, Greenland.

This is an artist's illustration of Antarctica, 250 million years ago. The newly discovered fossil of a dinosaur relative, Antarctanax shackletoni, revealed that reptiles lived among the diverse wildlife in Antarctica after the mass extinction.

Bone points and pierced teeth found in Denisova Cave were dated to the early Upper Paleolithic. A new study establishes the timeline of the cave, and it sheltered the first known humans as early as 300,000 years ago.

This artist's illustration shows a marine reptile similar to a platypus hunting at dusk. This duckbilled animal was the first reptile to have unusually small eyes that most likely required it to use other senses, such as the tactile sense of its duckbill, to hunt for prey.

Although it's hard to spot, researchers found flecks of lapis lazuli pigment, called ultramarine, in the dental plaque on the lower jaw of a medieval woman.

A Neanderthal fossil, left, and a modern human skeleton. Neanderthals have commonly be considered to show high incidences of trauma compared with modern humans, but a new study reveals that head trauma was consistent for both.

The world's oldest figurative artwork from Borneo has been dated to 40,000 years ago, when humans were living on what's now known as Earth's third-largest island.

A 250,000-year-old Neanderthal child's tooth contains an unprecedented record of the seasons of birth, nursing, illness and lead exposures over the first three years of its life.

An artist's illustration shows giant nocturnal elephant birds foraging in the ancient forests of Madagascar at night. A new study suggests that the now-extinct birds were nocturnal and blind.

Kebara 2 is the most complete Neanderthal fossil recovered to date. It was uncovered in Israel's Kebara Cave, where other Neanderthal remains have been found.

The world's oldest intact shipwreck was found by a research team in the Black Sea. It's a Greek trading vessel that was dated to 400 BC. The ship was surveyed and digitally mapped by two remote underwater vehicles.

This fossil represents a new piranha-like fish from the Jurassic period with sharp, pointed teeth. It probably fed on the fins of other fishes.

The fossil skull of the young Diplodocus known as Andrew, held by Cary Woodruff, director of paleontology at the Great Plains Dinosaur Museum.

Two small bones from the Ciemna Cave in Poland are the oldest human remains found in the country. The condition of the bones also suggests that the child was eaten by a large bird.

This artist's illustration shows the newly discovered dinosaur species Ledumahadi mafube foraging in the Early Jurassic of South Africa. Heterodontosaurus,another South African dinosaur, can also be seen in the foreground.

A 73,000-year-old red cross-hatch pattern was drawn on a flake of silicrete, which forms when sand and gravel cement together, and found in a cave in South Africa.

A suite of Middle Neolithic pottery including typical Danilo ware, figulina and rhyta that was used to hold meat, milk, cheese and yogurt.

These four dinosaurs showcase the evolution of alvarezsaurs. From left, Haplocheirus, Xiyunykus, Bannykus and Shuvuuia reveal the lengthening of the jaws, reduction of teeth and changes in the hand and arm.

Eorhynchochelys sinensis is an early turtle that lived 228 million years ago. It had a toothless beak, but no shell.

The leg bones of a 7-year-old, recovered from an ancient Roman cemetery, show bending and deformities associated with rickets.

The famed Easter Island statues, called moai, were originally full-body figures that have been partially covered over the passage of time. They represent important Rapa Nui ancestors and were carved after a population was established on the island 900 years ago.

Researchers stand at the excavation site of Aubrey Hole 7, where cremated human remains were recovered at Stonehenge to be studied. New research suggests that 40% of 25 individuals buried at Stonehenge weren't from there -- but they possibly transported stones from west Wales and helped build it.

The fossil of the newly discovered armored dinosaur Akainacephalus johnsoni was found in southern Utah.

The foot is one part of a partial skeleton of a 3.32 million-year-old skeleton of an Australopithecus afarensis child dubbed Selam.

The asteroid impact that caused dinosaurs to go extinct also destroyed global forests, according to a new study. This illustration shows one of the few ground-dwelling birds that survived the toxic environment and mass extinction.

The remains of a butchered rhinoceros are helping researchers to date when early humans reached the Philippines. They found a 75% complete skeleton of a rhinoceros that was clearly butchered, with 13 of its bones displaying cut marks and areas where bone was struck to release marrow, at the Kalinga archaeological site on the island of Luzon.

This is just one of 26 individuals found at the site of a fifth-century massacre on the Swedish island of Ûland. This adolescent was found lying on his side, which suggests a slower death. Other skeletons found in the homes and streets of the ringfort at Sandby borg show signs of sudden death by blows to the head.

The skeleton of a young woman and her fetus were found in a brick coffin dated to medieval Italy. Her skull shows an example of neurosurgery, and her child was extruded after death in a rare "coffin birth."

This portion of a whale skull was found at the Calaveras Dam construction site in California, along with at least 19 others. Some of the pieces measure 3 feet long.

A Stone Age cow skull shows trepanation, a hole in the cranium that was created by humans as as surgical intervention or experiment.

On the left is a fossilized skull of our hominin ancestor Homo heidelbergensis, who lived 200,000 to 600,000 years ago. On the right is a modern human skull. Hominins had pronounced brow ridges, but modern humans evolved mobile eyebrows as their face shape became smaller.

On the left is a 13,000-year-old footprint as found in the sediment on Calvert Island, off the Canadian Pacific coast. On the right is a digitally enhanced image, showing details of the footprint.

A central platform at Star Carr in North Yorkshire, England, was excavated by a research team studying past climate change events at the Middle Stone Age site. The Star Carr site is home to the oldest evidence of carpentry in Europe and of built structures in Britain.

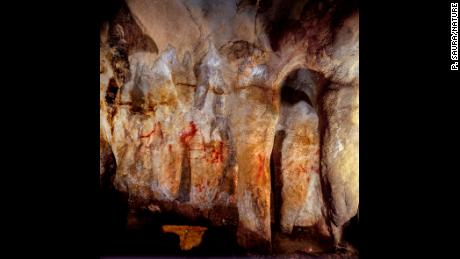

This wall with paintings is in the La Pasiega Cave in Spain. The ladder shape of red horizontal and vertical lines is more than 64,000 years old and was made by Neanderthals.

These perforated shells were found in Spain's Cueva de los Aviones sea cave and date to between 115,000 and 120,000 years ago. Researchers believe these served as body ornamentation for Neanderthals.

The earliest modern human fossil ever found outside of Africa has been recovered in Israel. This suggests that modern humans left Africa at least 50,000 years earlier than previously believed. The upper jawbone, including several teeth, was recovered in a prehistoric cave site.

This is an excavated structure at the northern edge of the Grand Plaza at Teposcolula-Yucundaa in Oaxaca, Mexico. Researchers investigated a "pestilence" cemetery associated with a devastating 1545-1550 epidemic. New analysis suggests that salmonella caused a typhoid fever epidemic.

Standing about 4 feet tall, early human ancestor Paranthropus boisei had a small brain and a wide, dish-like face. It is most well-known for having big teeth and hefty chewing muscles.