Stars may appear bright to us on Earth, but peering inside their hearts is a little more elusive. Star data from NASA’s planet-hunting TESS mission hashelped an international team of scientists detect patterns in 60 pulsating stars.

This data revealed the internal structures of the stars, which could aid in the understanding of what’s happening in billions of stars across the universe.

Essentially, the researchers could listen in to the heartbeats of the stars, which created a kind of music. The study published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

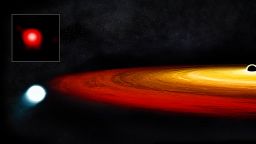

This particular class of stars are known as the Delta Scuti stars. They get their name from a bright star, Delta Scuti, in the Scutum constellations and they’re each about 1.5 to 2.5 times the mass of our sun.

Previously, astronomers were able to detect pulsations in these stars, but they couldn’t determine a pattern.

Pulsations are natural resonances that come from the stars, formed by trapped waves similar to those in musical instruments. These sound waves travel from within the star to create pulsation patterns at their surfaces. To astronomers, these appear as changes in the star’s brightness.

A pulsating mystery

When stars pulsate astronomers can learn key details about them.

These movements back and forth inside of stars, called oscillations, can reveal their inner workings. This is called asteroseismology, which is when we learn more about stars by measured changes in the star’s light.

It’s similar to how earthquakes allow us to study Earth’s interior in seismology.

For example, the changes in brightness of our sun have provided astronomers with information about its temperature and chemical makeup, as well as the processes occurring inside it.

Asteroseismology has been used to understand stars like our sun, high-mass stars, red giants and white dwarfs. But Delta Scuti stars confounded scientists until now.

This is because while “many stars pulsate along simple chords,” the tune of the Delta Scuti stars is much more complex, said Tim Bedding, lead study author and professor at the University of Sydney, in a statement.

Delta Scuti stars rotate once or twice a day, which is much quicker, and about a dozen times faster, than our sun. That can shake up the pulsation patterns and make them difficult to interpret.

“The signals from these stars have been a mystery for over a hundred years,” said Daniel Huber, study co-author and assistant professor at the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy. “We knew that brightness variations in these stars are caused by sound waves traveling in their interior, but we just couldn’t make any sense of them.”

The TESS mission, which was designed to detect exoplanets, or planets outside of our solar system, around nearby stars, captures data about star brightness. When astronomers used TESS data, they could narrow their focus to 60 Delta Scuti stars, between 60 to 1,400 light-years away from Earth, with clear pulsations in brightness. These regularly pulsed with high frequency.

The TESS data needed to be processed through software, which was designed by Daniel Hey, study co-author and a doctoral studentat the University of Sydney.

“We needed to process all 92,000 light curves, which measure a star’s brightness over time,” Hey said in a statement.

“From here we had to cut through the noise, leaving us with the clear patterns of the 60 stars identified in the study. Using the open-source Python library, Lightkurve, we managed to process all of the light curve data on my university desktop computer in a just few days.”

Observations from the W. M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea in Hawaii also revealed that the regular patterns came from Delta Scutti stars that were spinning slower than normal, which could help explain their frequency patterns. Follow-up observations were also conducted using the global Las Cumbres Observatory network.

Listening to celestial heartbeats

“Previously we were finding too many jumbled up notes to understand these pulsating stars properly,” Bedding said.

“It was a mess, like listening to a cat walking on a piano. The incredibly precise data from NASA’s TESS mission have allowed us to cut through the noise. Now we can detect structure, more like listening to nice chords being played on the piano.”

Huber compared it to “notes of a song finally falling into place to play a beautiful melody.”

And pulsations by Delta Scuti stars can reveal their mass, age and internal structure.

“Our results show that this class of stars is very young and some tend to hang around in loose associations. They haven’t got the idea of ‘social distancing’ rules yet,” Bedding said.

Young stars allow astronomers the chance to see how stars evolve, as well as the formation and evolution of planets around them – kind of like peering back into the formation of our own solar system, said Eric Gaidos, study co-author and professor in the University of Hawaii’s School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology.

“Some of the stars in our sample host planets, including beta Pictoris, just 60 light years from Earth and which is visible to the naked eye from Australia,” said Isabel Colman, study co-author and doctoral candidate at the University of Sydney, in a statement. “The more we know about stars, the more we learn about their potential effects on their planets.”

It’s a breakthrough for the researchers and they plan to continue observing Delta Scuti stars with TESS going forward. Although TESS was designed to find exoplanets, there were also hopes that it could help advance asteroseismology – and it’s just getting started.

“We are thrilled that TESS data is being used by astronomers throughout the world to deepen our knowledge of stellar processes,” said George Ricker, study co-author and TESS Principal Investigator at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research in Cambridge, in a statement.

“The findings have opened up entirely new horizons for better understanding a whole class of stars.”