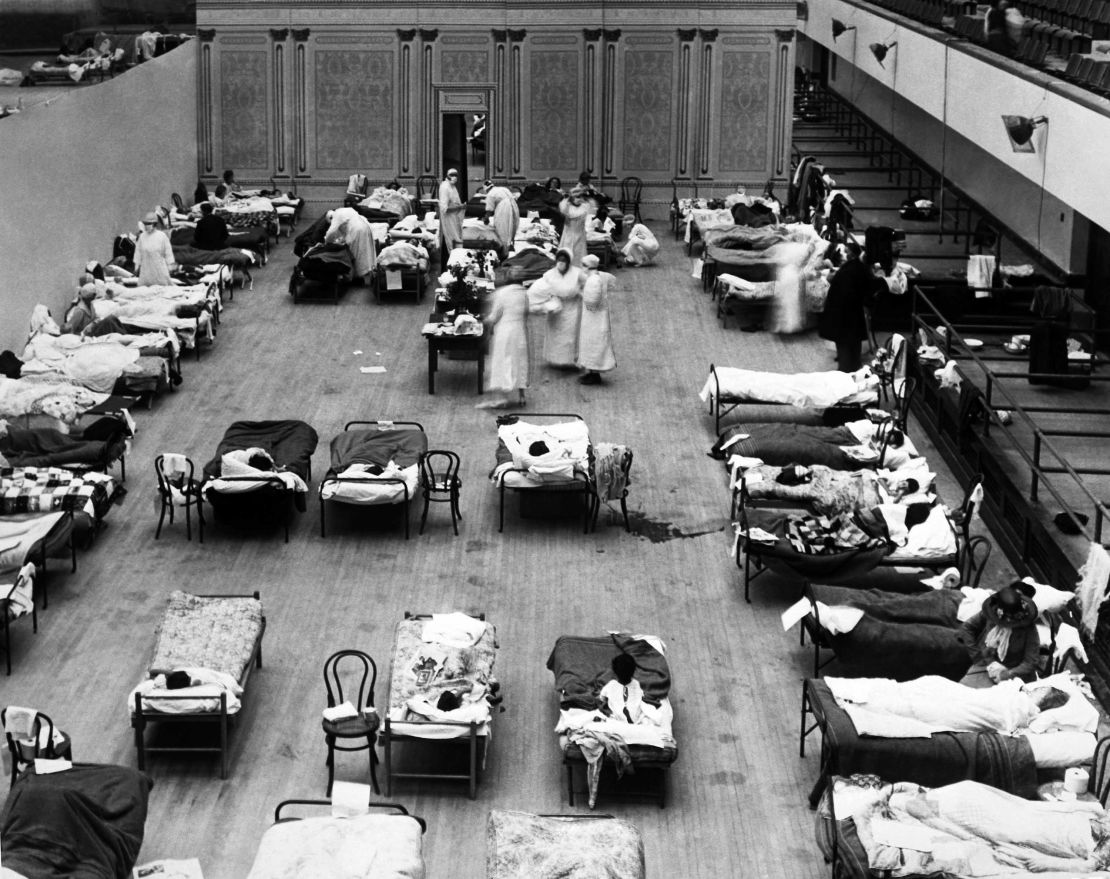

A pandemic ravaged the world like wildfire, killing more than 50 million people globally and about 675,000 in the US.

“The intensity and speed with which it struck were almost unimaginable – infecting one-third of the Earth’s population,” the World Health Organization said.

That was the 1918 influenza pandemic. The virus was often called the “Spanish flu,” even though it didn’t originate in Spain.

Fast-forward to 2020, and the novel coronavirus is also spreading with astonishing speed.

Some of the painful lessons learned from the 1918 pandemic are still relevant today – and could help prevent an equally catastrophic outcome.

Lesson #1: Don’t let up on social distancing too soon

During the 1918 flu pandemic, people stopped distancing too early, leading to a second wave of infections that was deadlier than the first, epidemiologists say.

In fact, one large gathering near the end of the first wave in 1918 helped fuel the deadlier second wave.

In San Francisco, when the number of cases was almost down to zero, “the city fathers said, ‘Let’s open up the city. Let’s have a great big parade downtown. We’ll all take off our masks together,’” epidemiologist Dr. Larry Brilliant said.

“Two months later, because of that event, the great influenza came back again roaring.”

On the other side of the US, Philadelphia suffered a similar fate.

Even though 600 sailors from the Philadelphia Navy Yard had the virus in September 1918, the city didn’t cancel a parade scheduled for September 28, 1918.

Three days later, Philadelphia had 635 new cases of the flu, according to the University of Pennsylvania Archives & Records Center.

“Quickly, Philadelphia became the city with the highest influenza death toll in the US,” Penn research states.

By contrast, St. Louis – which scheduled a similar parade but canceled it – fared much better.

“The next month, more than 10,000 people in Philadelphia died from pandemic flu, while the death toll in Saint Louis did not rise above 700,” the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said.

Of course, different places will reach different peaks at different times. But just because one place moves past a so-called peak with coronavirus doesn’t mean cases or deaths there can’t rise again.

“The image that we have of this epidemic curve, we say we’re going to reach a ‘peak’ – we look at it, it looks like Mt. Fuji in our minds … a single, solitary mountain,” Brilliant said.

“I don’t think it’s going to look like that. I think a better image is a wave of a tsunami, with echoed waves that follow. And it’s up to us, how big those other waves will be.”

Lesson #2: Young, healthy adults can be victims of their strong immune systems

The 1918 pandemic killed many young adults who were otherwise healthy, said John M. Barry, professor at the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine.

About two-thirds of the deaths then were among people ages 18 to 50, “and the peak age for death was 28,” said Barry, author of “The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History.”

In the years leading up the 1918 flu pandemic, the life expectancy in the US was in the early 50s. But in just one year after it struck, the average US life expectancy dropped by 12 years.

As of 2017, the average US life expectancy was 78.6 years. And with coronavirus, the elderly and those with underlying health problems are at higher risk for severe complications.

Yet many young, healthy people are also getting severely sick with or dying from Covid-19.

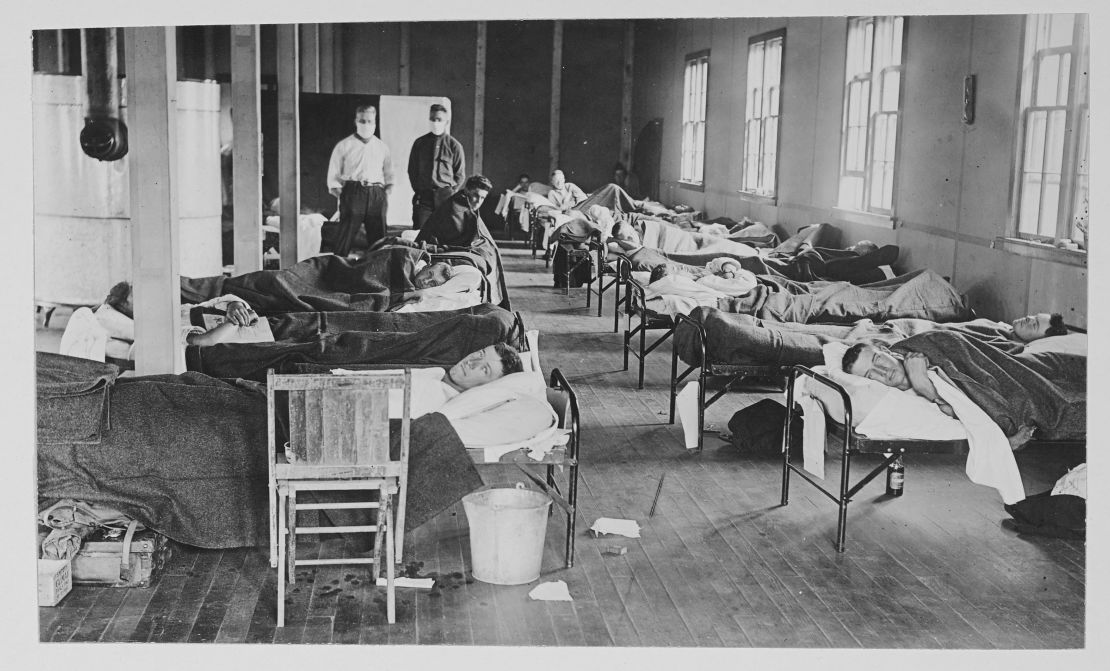

One reason the 1918 flu was so deadly for young adults was because the outbreak started during World War I, when many soldiers were in barracks and in close proximity with each other.

“The US military training camps obviously had high mortality,” Barry said.

There’s no world war now, but important lessons remain: Young, healthy people are not invincible. And their strong immune systems might work against them.

Looking back at the 1918 pandemic, scientists now believe an “immune system overreaction contributed to high death rates among otherwise healthy young adults in 1918,” wrote Dr. Richard Gunderman, chancellor’s professor of medicine at Indiana University.

A century after that pandemic, hyperactive immune systems could also be contributing to young people’s deaths from coronavirus, CNN Chief Medical Correspondent Dr. Sanjay Gupta said. These overly strong responses are often called cytokine storms.

“In some young, healthy people, a very reactive immune system could lead to a massive inflammatory storm that could overwhelm the lungs and other organs,” Gupta said.

“In those cases, it is not an aged or weakened immune system that is the problem – it is one that works too well.”

Lesson #3: Don’t throw unproven drugs at the virus

Back in 1918, remedies “varied from the newly developed drugs to oils and herbs,” according to a Stanford University research post. “The therapy was much less scientific than the diagnostics, as the drugs had no clear explanatory theory of action.”

In 2020, there is widespread speculation about whether hydroxychloroquine – a drug used to treat malaria, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis – could help coronavirus patients.

President Donald Trump has touted hydroxychloroquine, saying, “What do you have to lose? Take it.” After that, some started hoarding the drug – even though it’s still being tested and might not even work against coronavirus.

A recent study found hydroxychloroquine did not help hospitalized coronavirus patients – instead, some patients developed abnormal heart rhythms.

'Unseen Enemy: Pandemic'

“This provides evidence that hydroxychloroquine does not apparently treat patients with Covid 19,” said Dr. Paul Offit, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“Even worse, there were side effects caused by the drug – heart toxicities that required it be discontinued.”

Doctors in Brazil and Sweden have also raised concerns about using chloroquine, a drug very similar to hydroxychloroquine, on coronavirus patients because of heart problems.

The bottom line: It’s still not clear whether some drugs will cause more harm than good in the fight against coronavirus.

You asked, we’re answering: Your top coronavirus questions

CNN’s Leah Asmelash, Elizabeth Cohen and Dr. Minali Nigam contributed to this report.