The rapid spread of coronavirus has sent states scrambling to buy ventilators to prepare for a coming apex of cases.

But ventilators do not operate on their own. And while the ventilator shortage remains a serious issue, much less attention has been paid to the health care workers needed to operate those machines: respiratory therapists.

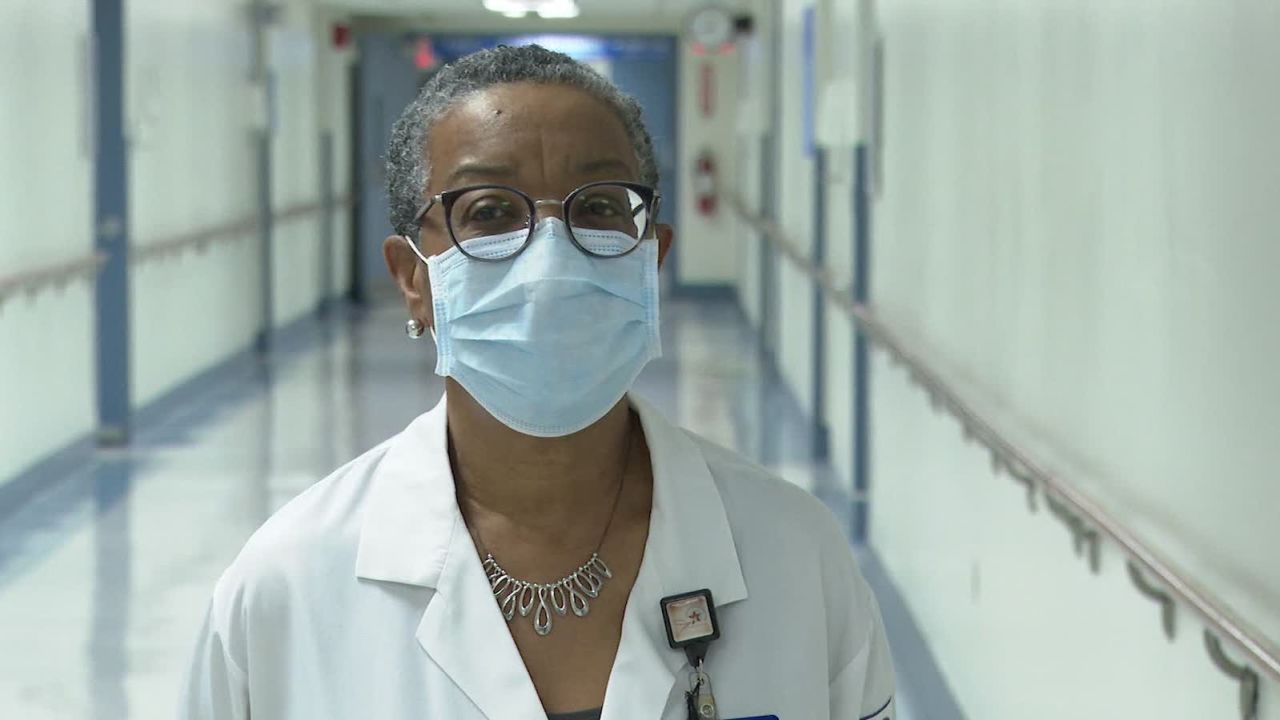

“It’s not just this machine they talk about on TV that we don’t have enough of. It’s very complex,” said Julie Eason, the respiratory therapy department director at University Hospital in Brooklyn, part of the SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University.

“If you don’t set it up right, that patient outcome is different. You need skilled people who have lots of experience doing this to have good outcomes with these patients,” she said.

Enter the respiratory therapist, who is specially trained to treat people with breathing problems. Amid the coronavirus pandemic, their role as master of the mechanical ventilator has brought them a new level of recognition for what has long been an unfamiliar job.

“When I tell people I’m a respiratory therapist, they look at me with a blank stare,” said Lisa Shultis, a respiratory therapist and director for Long Island University’s respiratory care program. “Until this time. Now they look at me with fear.”

Respiratory therapists are the ones who track Covid-19 patients’ oxygen levels, manage their breathing and, if need be, intubate them and set up a mechanical ventilator.

There are 155,000 licensed respiratory therapists in the US, according to American Association for Respiratory Care (AARC). The job’s median salary is just over $60,000 per year, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Still, their work remains “virtually unknown,” said Tom Kallstrom, the CEO and executive director of the AARC.

“On doctor (TV) shows, they never really show respiratory therapists,” he said. “They show others doing what we do. I’m grateful to know that at least people know who we are (now).”

What respiratory therapists do

As the name suggests, respiratory therapists focus on breathing – the issue at the core of the pandemic.

In normal times, respiratory therapists treat acute conditions, such as premature babies with underdeveloped lungs or adults with heart attacks, as well as chronic issues, such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Now, though, coronavirus is the focus. Coronavirus causes Covid-19, which affects the lungs and can lead to pneumonia, shortness of breath and, in worst-case scenarios, acute respiratory distress syndrome, known as ARDS.

“These patients are so different from any patients we have ever seen before,” Eason said. “We normally have a couple patients that are this level sick. (Now) our ICUs are filled with them. And filled with them. None of them can breathe.”

One treatment for these issues is to provide supplemental oxygen through a nasal cannula, a device that goes into a patient’s nose. If that doesn’t work, then a more extreme treatment is to stick a tube down a patient’s throat, known as intubation, and connect them to a mechanical ventilator that breathes for them. That’s often a deteriorating patient’s last best hope to recover.

Respiratory therapists are tasked with tracking the patient’s oxygen levels and working with physicians to decide if and when to use those treatments.

“It requires a lot of knowledge, experience and skill to be able to advise a physician on the best way to ventilate,” said Tom Barnes, lead faculty member and consultant for Northeastern University’s Master of Science in Respiratory Care Leadership program.

Their work helps alleviate the responsibilities of physicians and nurses.

“Neither party really has the background and training on mechanical ventilators that a respiratory therapist has,” Kallstrom said. “It’s really a three-legged stool. You really need your doctor, nurse and respiratory therapist continually working together.”

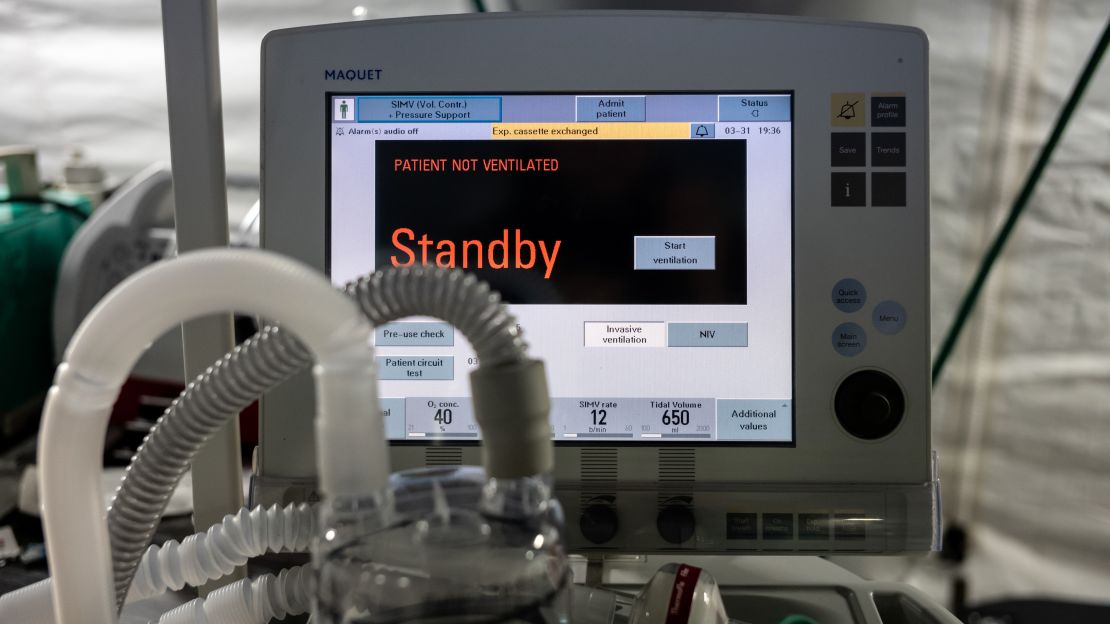

Respiratory therapists sometimes are the ones who physically do the intubations. They set up and manage the ventilators. They then work its controls to adjust for the patient’s needs: the size of the breath, the number of breaths per minute, the oxygen concentration, the airway pressure and more variables. And they set up alarms on the machine so that, if something goes wrong, the ventilator will alert nearby workers quickly.

“It’s like if you were to sit in the cockpit of an airplane, you wouldn’t know what to do,” said Kallstrom. “I don’t think a ventilator is that confusing necessarily, but there are a lot of buttons and modes that a modern-day ventilator has.”

It can be dangerous, too. Because respiratory therapists sometimes are the ones doing the intubations, hovering over an infected patient’s open airways, they are particularly at risk of catching the virus.

“You have to see where you’re going with that tube down the trachea, not the esophagus. It’s very difficult when you’ve got a mask, goggles, everything on,” Shultis said. “The patient is having exhaled breaths in your face. So that’s why it’s very dangerous. That’s why it’s imperative that we have the right (personal protective equipment) for whomever is in the room, but especially for respiratory therapists.”

Shultis, Kallstrom and Barnes said they have been frustrated watching officials and the media discuss the need for ventilators without acknowledging the role of respiratory therapists.

“They’re out there working their hearts out and it’s especially hard when people don’t acknowledge them,” Barnes said.

It’s not just national figures, either. Shultis said even inside hospitals, respiratory therapists often aren’t acknowledged on level footing with other health care workers.

“Call us by our name. We are not just the people who run the ventilators. We’re respiratory therapists. We’re an important profession on the health care team,” she said.

CNN’s Lauren del Valle and Miguel Marquez contributed to this report.