Archaeologists say they’ve found the long-lost capital of an ancient Maya kingdom near the border between Mexico and Guatemala.

The Sak Tz’i’ kingdom was home to between 5,000 and 10,000 people in what is now Chiapas, Mexico, from about 750 BCE to 900 AD, Brandeis University associate professor of anthropology Charles Golden told CNN.

The kingdom wasn’t particularly powerful and was surrounded by some of the superpowers of the day, Golden said. He said the Sak Tz’i’ kingdom was frequently mentioned in inscriptions found in other cities.

“The reason we know about the kingdom from the inscriptions is because they get beat up by all these superpowers, their rulers are taken captive, they’re fighting wars, but they’re also negotiating alliances with those superpowers at the same time,” he said.

The downtown area was about a third of a mile long and a quarter mile wide (600 meters by 400 meters) and had pyramids, a royal palace, a ball court and a number of houses.

“These are not big empires. They’re small city-states trying to carve out their little, little territories,” Golden said.

Golden and Brown University bioarchaeologist Andrew Scherer are leading the team that has been excavating the site since 2018. They published their findings in the Journal of Field Archaeology.

Golden said they found out about the site after graduate student Whittaker Schroder got a tip from a street food vendor, who introduced him to the rancher who owned the property.

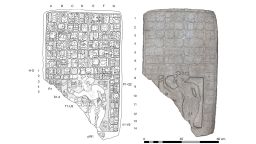

The rancher had a stone tablet that had an inscription and a drawing of a Sak Tz’i’ king dressed as the Maya storm god.

Golden said the site had been raided by looters in 1960s and many of its monuments were stolen. The owner found the stone tablet in some rubble while working to protect what is left of the site.

“He found it by accident. There’s a lucky, lucky rescued object the looters had missed,” Golden said.

Golden said the looters used saws and other heavy equipment to cut the off faces of the monuments. The pieces wound up in museums and private collections around the world.

“When you go to the museum and see these objects, you’re seeing something that’s been really butchered from its original piece of stone, so we would try to reconnect it to the original piece of stone that may still be on on site,” he said.

He said it’s taken years to build trust in the community and get permission to dig at the site.

“We are both excavating to find out how people lived and more about how they built these places, but we also have to conserve these buildings,” Golden said. “They were damaged by looters and we’ll be working with the landowner to stabilize and keep these buildings from further deterioration.”

He said he hopes the discovery will help them learn how these smaller kingdoms and their citizens lived their lives and negotiated living between their powerful, feuding neighbors.