After more than 16 years of observations, NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope came to an end on Thursday. It leaves a legacy of discoveries in its wake, which in turn has created new questions and intriguing targets for follow-up observations.

Spitzer was our infrared detective, spying exoplanets and distant galaxies. Now, there’s a gap in infrared observations until NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope launches in 2021. This large infrared telescope will be the premier observatory of the next decade, according to NASA.

It was named for former NASA administrator James Webb, who ran the agency during the Space Race from February 1961 to October 1968. NASA said that while Webb is linked to the Apollo program, he also supported the agency’s balance of human space flight and science.

But scientists aren’t worried about the gap. Exoplanet science continues through NASA’s planet-hunting TESS mission, which has already found over 1,000 exoplanet candidates in its first year of science operations. The mission has been approved by NASA for another three years of observations, according to the agency.

Spitzer helped scientists lay the groundwork for determining what exoplanets look like, and even helped them learn how to operate telescopes in space in order to make the observations achieved over the last 16 years.

“When Webb gets up there, we can hit the ground running in a way we couldn’t do with Spitzer,” said Nikole Lewis, astrophysicist and assistant professor of astronomy at Cornell University.

Each telescope builds on the knowledge gained from the previous one. In the case of James Webb, its mirror is 50 times larger and it can observe even deeper into the universe.

Webb will be able to characterize exoplanets, going beyond Spitzer’s capabilities of measuring how big a planet is and seeing the intricate details of how they look, Lewis said.

“We’re hoping to answer those questions that Spitzer couldn’t solve for us,” she said.

Webb will take a closer look at a selection of exoplanets to peer inside their atmospheres, if they have them, and help answer questions about how the planets formed and evolved. Its spectroscopic data can tell scientists if methane, carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide is in the atmosphere.

Spitzer and TESS have helped scientists establish targets for follow-up by Webb, including some of Spitzer’s “greatest hits,” Lewis said.

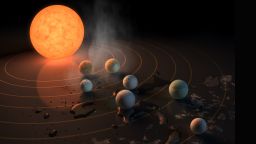

For example, in February 2017 astronomers announced their discovery of seven Earth-size planets orbiting a star 40 light-years from Earth. With Spitzer’s help, the seven exoplanets were all found in tight formation around an ultracool dwarf star called TRAPPIST-1.

The planets all bear the TRAPPIST name – which the researchers borrowed from their favorite beer. Sean Carey, manager of the Spitzer Science Center at the California Institute of Technology, looks forward to Webb’s follow-up of the system, which can provide a more detailed analysis on these intriguing planets.

Some of the planned targets for Webb include TRAPPIST-1b and TRAPPIST-1e, which could support liquid water on their surfaces. Another planned target for early in the mission is WASP-18b, a blazing hot Jupiter with an atmosphere, according to NASA.

Webb is also well-equipped to shed light on the mysteries of planet formation. Building off Spitzer’s work studying brown dwarfs, or objects that are too large to be planets but too small to be stars, Webb can take a closer look at their cloud properties.

Spitzer was known for looking deep into the universe, studying galaxies that formed in the early days of the Big Bang. Webb is more sensitive, so it will be able to peer back even further.

“We’ll be able to see some of the earliest galaxies to form in the universe that we’ve never seen before,” said Amber Straughn, deputy project scientist for James Webb Space Telescope Science Communications.

Like Spitzer, the Webb telescope was in development while scientists were learning about exoplanets, but it wasn’t optimized for them. For example, the concept for Spitzer was initially developed in the 1970s; it launched in 2003.

“It takes a long time to develop an observatory,” Carey said. “So the expectation for James Webb is tremendous.”