Editor’s Note: James Griffiths is a Senior Producer for CNN International and author of “The Great Firewall of China: How to Build and Control an Alternative Version of the Internet.”

The Great Firewall of China has always been annoying, but it’s not usually this deadly.

As the Wuhan coronavirus continues to spread around China and the world, many are questioning how much the country’s colossal censorship apparatus played a role in withholding vital information about the epidemic until it was too late.

In the weeks after the virus was first detected in Wuhan, local and national authorities followed the usual playbook for any potential controversy: knee-jerk censorship and tight control of the narrative. Politicians downplayed the severity of the virus, while police went after “rumormongers” and censors deleted any commentary that questioned the official line.

As the crisis has worsened, however – with thousands of confirmed cases and hundreds of deaths nationwide – it has become clear that the failure to take quick action likely undermined any chance of containing the virus.

Heads will likely roll in Wuhan, where the city’s mayor Zhou Xianwang has already publicly offered to resign, admitting that his administration’s warnings were “not sufficient.”

But even as censorship has lessened somewhat in the face of intense public anger and scrutiny, allowing Chinese media to swarm Wuhan and blow holes in parts of the official line, the government continues to shape and control the story in China, and there are signs that any tolerance for dissent may already be slipping away.

The costs of control

Speaking to state broadcaster CCTV this week, Zhou said that Wuhan officials “understand that the public is unsatisfied with our information disclosure.”

But even as he was very publicly being set up as the fall guy, Zhou hinted that there was plenty of blame to go around. “I hope the public can understand that it’s an infectious disease, and relevant information should be released according to the law,” he said. “As a local government, we can only disclose information after being authorized.”

Indeed, for all their personal failings, officials in Wuhan operate in a national system which encourages exactly the type of approach they took.

Under Chinese President Xi Jinping, control over the media and internet has increased and tolerance for dissent and counter narratives has practically disappeared. Government critics and “rumormongers” have been arrested and imprisoned, and Chinese media’s already tight leash has been shortened further since he came to power.

This has allowed Xi to secure control of the Communist Party and the country, making him the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao Zedong, but it has also severely undermined the important watchdog role that the media and internet play on the government in freer societies. In most cases, this additional control is to the Party’s benefit, but the Wuhan crisis shows the dark side of only having the official narrative.

Even some Party officials seem to realize this. In a commentary published by the country’s Supreme Court this week, a senior judge condemned police in Wuhan for arresting “rumormongers” who, it has since emerged, were merely medical workers trying to warn people of the potential dangers of the new virus.

According to state media, those arrested included a doctor who told a private group chat that a new, SARS-like virus (severe acute respiratory syndrome) was spreading in Wuhan – something that was completely true. Speaking to the Global Times, one top health official praised them as “whistleblowers.”

“If the public listened to this ‘rumor’ at the time, and adopted measures such as wearing masks, strict disinfection and avoiding going to the wildlife market (at the center of the outbreak), this might have helped prevent and control the virus’ spread today,” the Supreme Court commentary said.

It added that “after this battle, we must learn profound lessons from it,” though it emphasized this does not mean abandoning the Party’s direction of “authoritative informational channels” or allowing widespread criticism.

Charlie Smith, founder of GreatFire.org, a censorship monitor, told CNN that “it’s a tough situation for the censors. Can you actually imagine being a censor at this moment and wondering if these rumors might actually be true?”

Smith has long predicted a breaking point for censorship in China, due in part to how it affects handling of crises like Wuhan. “This is one of those moments where it really could end, if the authorities decided it was more important to stop the virus from spreading than to protect the Party.”

Tolerance of dissent

China may have the most sophisticated censorship apparatus in the world, but a system of restriction that does not bend risks breaking entirely. Far from banning all dissent and discussion, it is instead allowed in a sudden burst, like a pressure valve releasing, and then quickly tightened up again.

This was the case after SARS in 2003, when the cover-up was far wider reaching and the blame spread across the entire government, leading to a rare public apology. It was also the case in 2011, when a high-speed rail crash saw a sudden flowering of citizen reporting and overoptimistic predictions that the Great Firewall was unable to control the new world of social media.

After both of those incidents, the Party maintained control and was able to rein in both an emboldened press and whatever new challenge would supposedly prove too much for the Firewall, be it blogs, social media, or encrypted messaging apps.

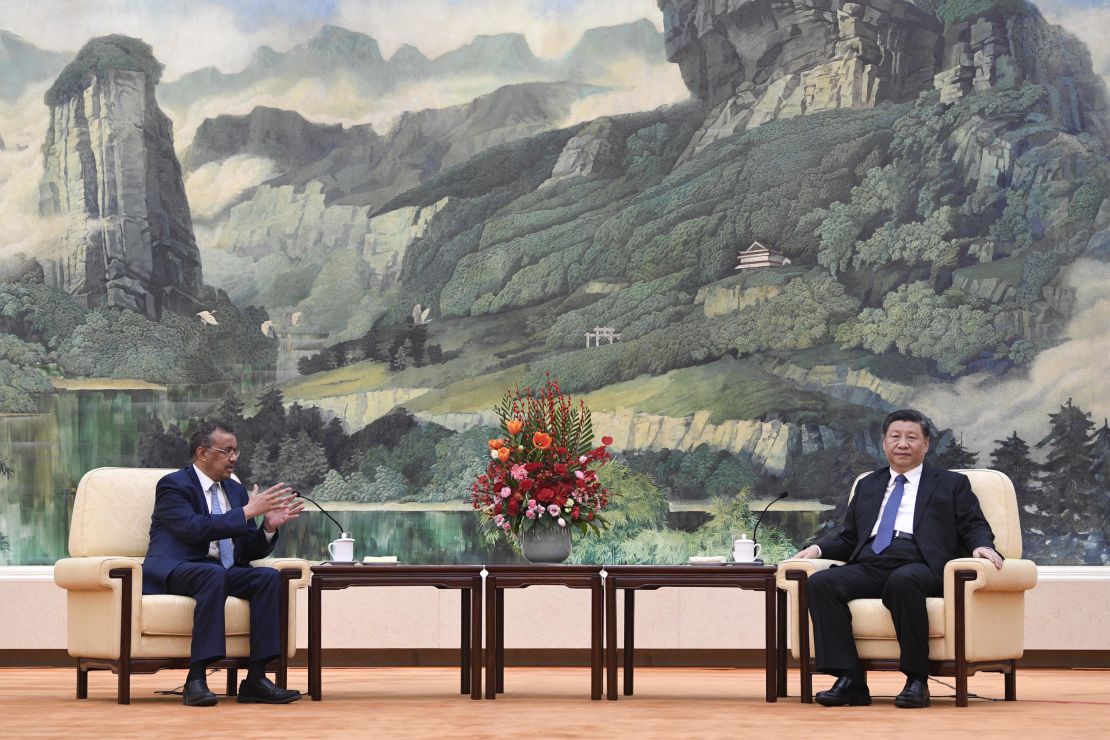

The head of the World Health Organization (WHO) has praised China for being “completely committed to transparency, both internally and externally,” and undoubtedly, the government has been far more open than it was in 2003, when it covered up details about SARS even from the WHO.

But as the (limited) public discussion of the Wuhan virus and response to it continues online for now, we are already seeing signs that greater control is on the horizon – especially as Xi assumes personal direction of the response, as any criticism of it risks undermining his authority.

Speaking at a meeting of a top level committee looking into the virus, Xi twice emphasized the importance of “strengthening the guidance of public opinion” – Party speak for censorship. He has also appointed Wang Huning, China’s top propagandist, to the second most senior place on the committee, behind only Premier Li Keqiang.

And for all the Supreme Court’s talk of tolerating rumors, China’s top social platforms know which way the wind is blowing. In a statement published by state media, the country’s biggest messaging app WeChat promised to “resolutely and continuously crack down on rumor-like information.”