To be Hong Kong Chief Executive is an impossible job, seemingly by design.

Pushed from one side by a public not afraid to take to the streets to challenge your decisions, and from the other by a hyper-controlling one-party state which demands stability above all else, it’s a wonder anyone wants the job.

In the 22 years since Hong Kong was handed over from British to Chinese rule, no chief executive has ever completed two terms, and incumbent Carrie Lam looks to be no different. On Wednesday, she finally announced the withdrawal of an extradition bill after three months of increasingly violent protests, which have roiled the city and damaged its economy.

The move came after a recording of Lam was leaked to Reuters in which she said “for a chief executive to have caused this huge havoc to Hong Kong is unforgivable. It’s just unforgivable. If I have a choice, the first thing is to quit.”

In a press conference on Tuesday, she criticized the leak and said she had not tendered a resignation to Beijing, nor even “contemplated to discuss a resignation” with her mainland superiors.

But while she may not be leaving yet, it seems highly unlikely that Lam will be able to seek a second term in 2022. Nor do many expect her to get much done before then, faced with an incredibly hostile public and elections next year that could offer the opposition gains in the legislature.

When she took the job, Lam struggled with a public perception that she was aloof and out of touch. Now her legacy is doomed to be far worse: the leader who fiddled while Hong Kong burned.

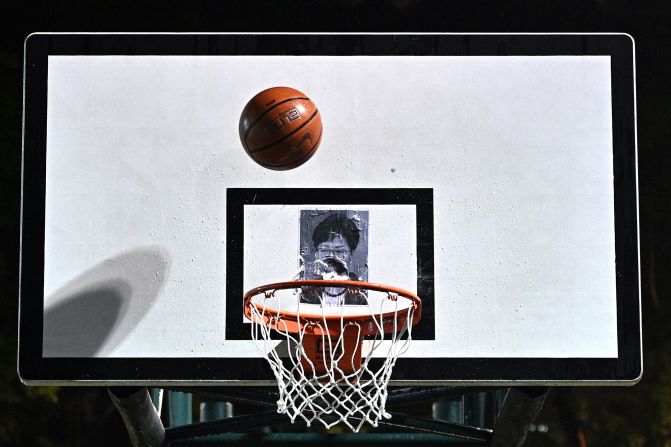

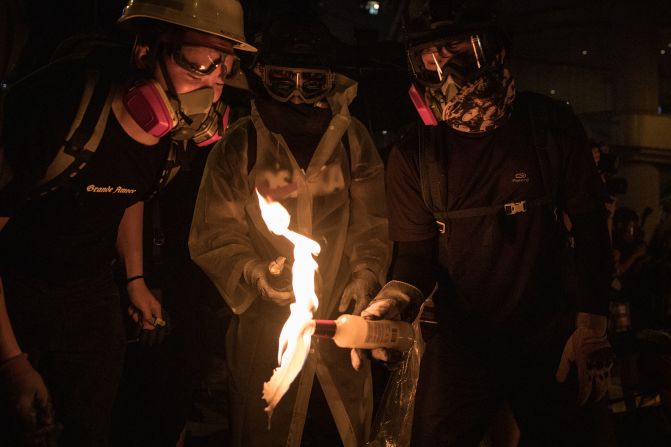

In pictures: Hong Kong unrest

Why Beijing won’t let Lam go

For many outsiders, it can seem bizarre that no Hong Kong officials have resigned after three months of chaos, which the government has accepted responsibility for starting, if not continuing. In many political systems, someone would have been pushed onto their sword if they would not politely fall on it.

Lam however, cannot leave. Her departure would cause more problems for Beijing than it would solve, with no obvious successor in place – unlike when Lam stood in the wings for her equally unpopular predecessor CY Leung – and a selection process that would open another huge can of worms.

Under the city’s constitution, if the office of chief executive becomes vacant, a successor must be selected “within six months.” Lam and all of her predecessors were chosen by an “election committee” which purports to represents a broad swath of society, but is dominated by pro-Beijing figures and follows the central government’s lead.

This situation has long been a point of contention in Hong Kong. An attempt to reform it ended with acrimony in 2014 when Beijing refused to allow candidates to stand without being pre-approved, kick-starting the Umbrella Movement protests.

Restarting that political reform process – achieving the “ultimate aims” of the constitution of electing both the chief executive and the entire legislature by universal suffrage – has been a demand of the current protests, albeit one that few but the most radical idealists expect to be achieved.

In a televised address Wednesday, Lam said implementing universal suffrage “is the ultimate aim laid down in the Basic Law,” the city’s constitution. “If we are to achieve this, discussions must be undertaken within the legal framework, and in an atmosphere that is conducive to mutual trust and understanding, and without further polarizing society,” she said.

But the can has been kicked down the road. There is not time to reform legislative elections before the next parliament is chosen next year, and Lam – or more likely her successor – will not face reselection until 2022.

From Beijing’s perspective, Lam’s resignation would only open an angry debate over reforming the chief executive’s selection, two years earlier than necessary, and continue Hong Kong’s summer of chaos.

Lame duck

In the remarks leaked to Reuters, Lam acknowledged that the “the political room for the chief executive who, unfortunately, has to serve two masters … that political room for maneuvering is very, very, very limited.”

More than any of her predecessors, she has demonstrated the limits of the office. Unable to take decisive action or make significant compromises without first running it past Beijing, many protesters regard her as little more than a puppet, making negotiations a non-starter for some because they don’t believe she has the power to decide anything.

In July, senior pro-democratic lawmaker Fernando Cheung said that even if the government succeeds in quashing the violence and getting past the current crisis, its chances of achieving anything before the end of Lam’s term is severely limited.

“Our younger generation has awakened. They have come to understand that the current political system does not work,” Cheung told CNN. “And even if the current campaign subsides in the future, any other new initiatives such as the national anthem law or the 1,000-acre man-made island that has been proposed by the chief executive. These measures would not go through without major protest. So, I think effectively, the government has become a lame duck.”

In the leaked speech, Lam said that while she was pessimistic, “Hong Kong is not dead yet.”

“Maybe she is very, very sick but she is not dead yet,” Lam said. “We will need to come back to life, some life. So thereafter we want a reborn Hong Kong and a relaunching of this Hong Kong brand.”

Hong Kong may yet be revived, images of police violence and protester petrol bombs replaced by peaceful scenes once again, but Lam’s brand is beyond saving.