We put a lot of trust in our doctors — we listen to theirdiagnoses, take out their prescriptions, follow their dietary suggestions. Would we do the same for a computer?

As the global market for artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare surges — expected to rise from $1.3 billion in 2019 to $10 billion by 2024, according to Morgan Stanley — it seems we may have to.

Deep learning is an AI approach modeled on the neural networks of the brain. It can analyze complex layers of information and identify abnormalities or trends in medical images.

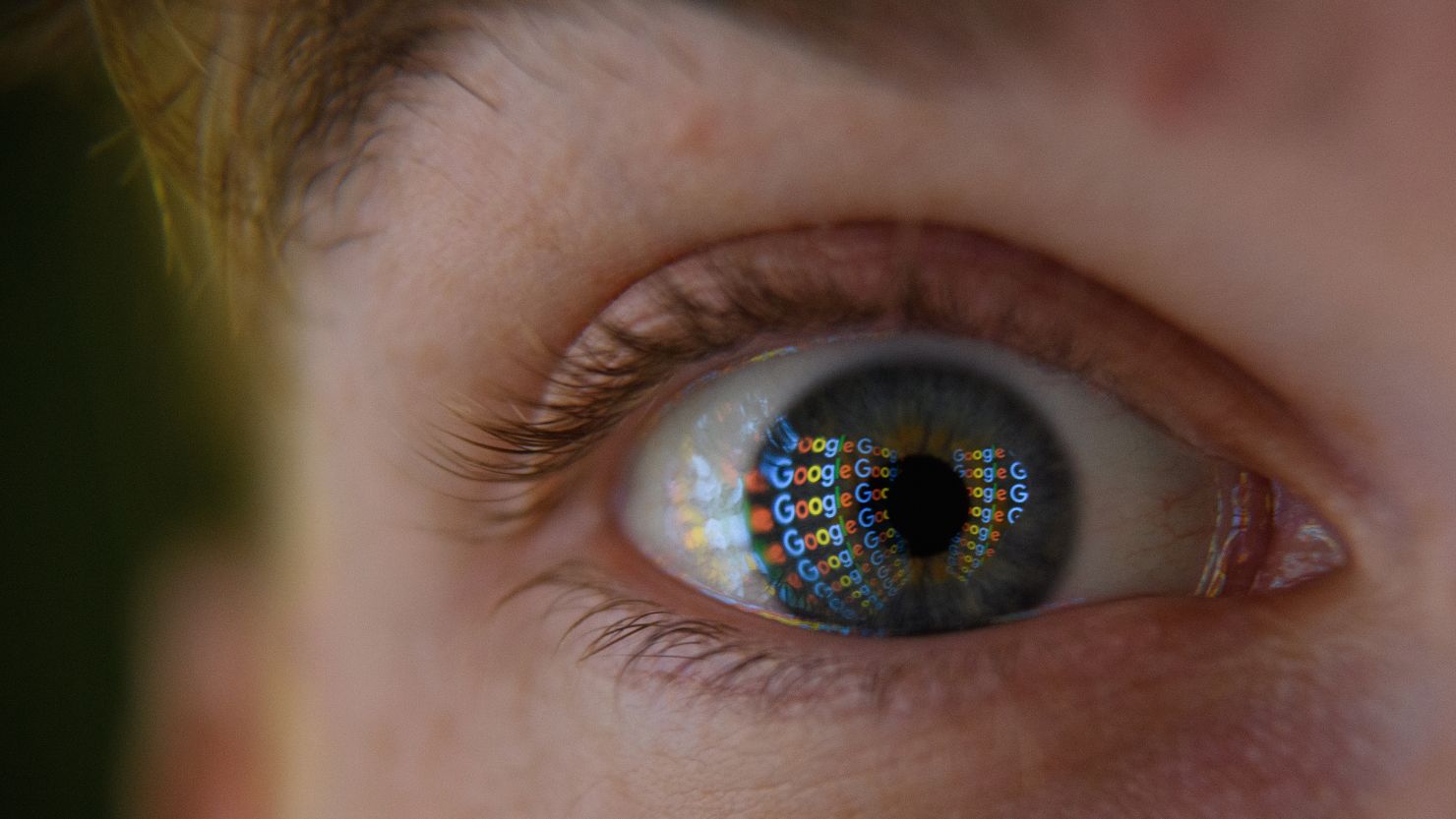

AI and eyes

Pearse Keane, a consultant ophthalmologist at Moorfields Eye Hospital, embraced the potential of deep learning five years ago.

“We’re drowning in the numbers of patients that we have to see, and because of that, there are some people who are losing sight irreversibly as they can’t get seen and treated quickly enough,” he tells CNN Business.

By applying the technology to OCT (Optical Coherence Tomography) scans, he thought it would help prioritize patients with sight-threatening diseases.

Keane approached DeepMind, a UK-based AI research center owned by Google (GOOGL), and with them developed an algorithm, trained on 14,884 retinal scans, that can return a detailed diagnosis in roughly 30 seconds.

It can detect 50 different eye diseases including glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration, provide a score and recommend how urgently patients should be referred for care.

Early results for the system, published inthe journal Nature Medicine, show that it has the same level of accuracy as leading specialists, correctly identifying types of eye disease 94.5% of the time.

However, before the technique can be implemented in Moorfields Eye Hospital and beyond it must pass through the lengthy process of regulatory approval and clinical trials.

“We’re tremendously excited about AI,” says Keane, “but also, we’re kind of cautious. We know that it has huge potential, but there are some ways that it might not work.”

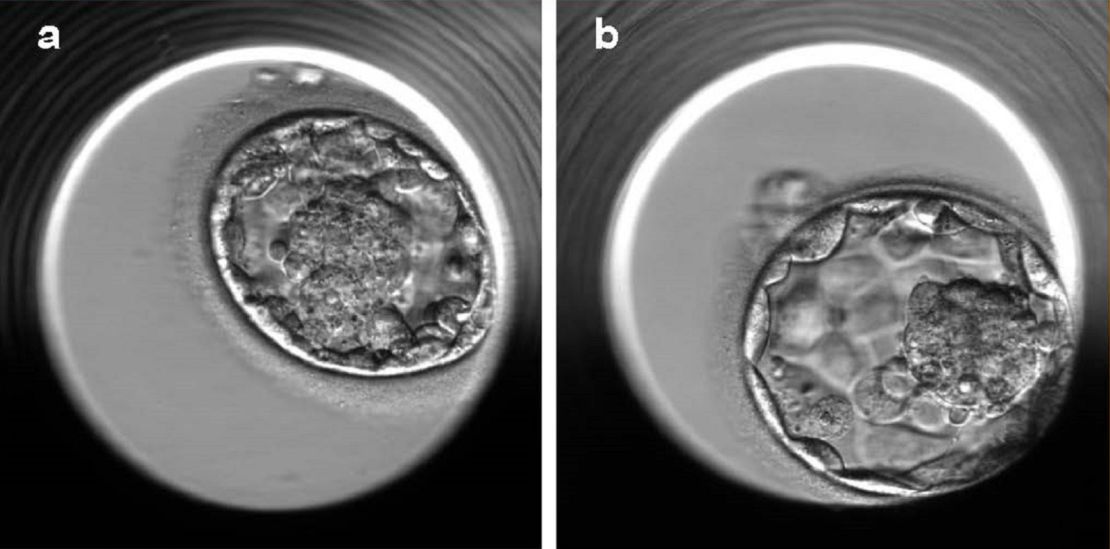

Improving IVF

Scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine are also deploying deep learning algorithms as a time-saving device, identifying which embryos have the best chance of developing into a healthy pregnancy during in vitro fertilization (IVF).

The algorithm, dubbed Stork, analyzes time-lapse images of early-stage embryos and is able to discriminate between poor and good embryo quality. According to the research paper published in NPJ Digital Medicine, it performed with 97% accuracy.

Usually this is a manual process, by which an embryologist sorts through multiple images, assigning a quality score that helps them decide which ones to implant first.

“Grading of the embryo by a human is very subjective,” Nikica Zaninovic, an embryologist at the Center for Reproductive Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, tells CNN Business. “Using AI to grade the embryos means we can do some standardization.”

The tool would also have a positive impact on the process of IVF as a whole. It could improve the success rate, minimize the risk of multiple pregnancies, and help to reduce the cost of the procedure, says Zev Rosenwaks, director of the Center for Reproductive Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Currently, the tool is only available to embryologists at Weill Cornell Medicine in an experimental setting. Expect it to be in practice more widely “within the next year or two,” says Zaninovic.

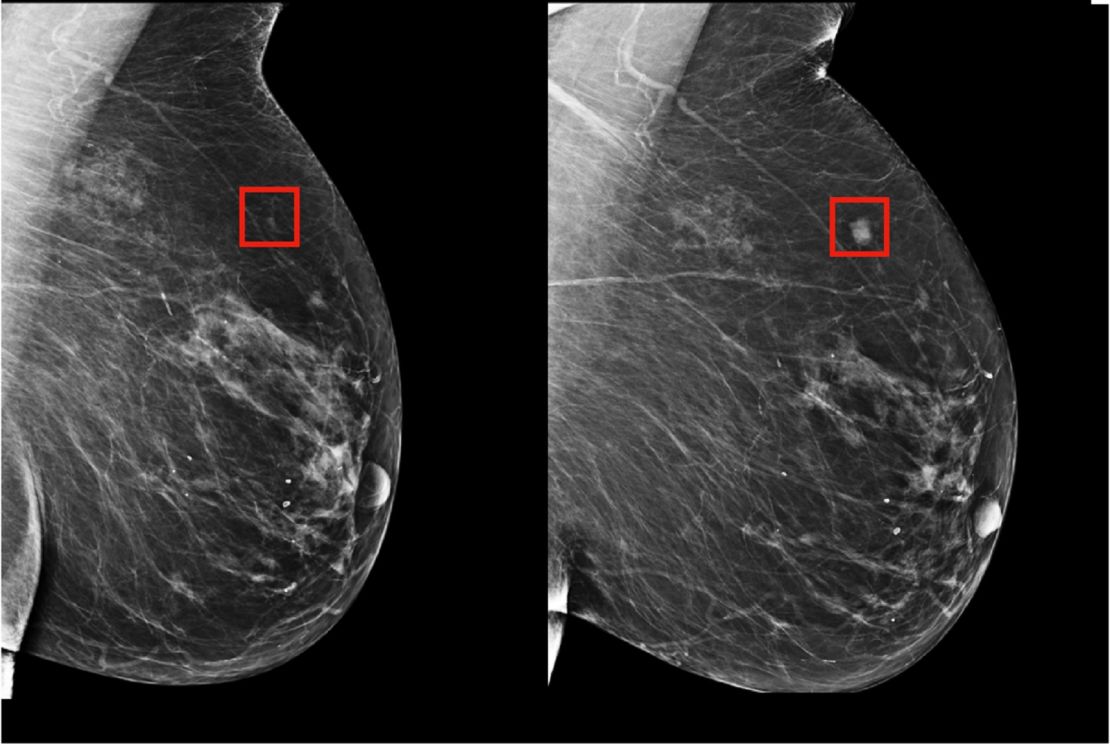

Predicting cancer risk

One initiative by MIT’s Computer Science and AI Lab can predict from a mammogram if a patient is likely to develop breast cancer in the future.

The model, trained on breast scans from 60,000 women, learned patterns in breast tissue that were precursors to cancer and too subtle for the human eye to detect. It outperformed existing approaches, placing 31% of all cancer patients in its highest-risk category compared to 18% for traditional models.

“I was interested in creating a model which can identify your future risk of cancer,” says Regina Barzilay, MIT professor and senior author of the study published in Radiology about the project.

As a breast cancer survivor herself, she subsequently applied the technology to her own mammograms. “I discovered that my cancer was in the breast two years before I was diagnosed,” she says.

Aged 43 at the time and with no history of breast cancer in the family, she had never considered herself at risk. But guidelines like these are unreliable, she says — only 15% to 20% of breast cancer cases are familial, according to a study from the Journal of Medical Genetics.

Using AI could identify women at risk and help them take preventative steps. “In the early stages cancer is a treatable disease … If we can identify many more women early enough, and either prevent their disease or treat them at the earliest stages, this will make a huge difference,” says Barzilay.

The model has been implemented in Massachusetts General Hospital, and they are in talks with other hospitals across the country and internationally, says Barzilay.