The Neanderthal genome was sequenced in 2010, but mystery still surrounds the early history of our extinct human relative.

Now, after researchers were able to extract nuclear genome sequences from two Neanderthal bones that predate others with sequenced genomes, a new study aims to answer some of the remaining questions.

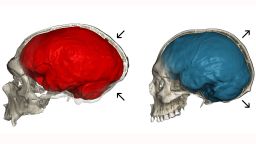

The study focuses on a jawbone belonging to a Neanderthal girl, first discovered within Scladina Cave, Belgium, in 1993 and the femur of a male Neanderthal from Hohlenstein-Stadel Cave, Germany, found in 1937. Both lived 120,000 years ago.

Evidence of Neanderthals extends as far back as 430,000 years ago. They seem to have disappeared and gone extinct about 40,000 years ago in Europe and Central Asia. Many of the Neanderthal remains that have been studied date to between 90,000 and 100,000 years ago.

The male and female bones in the new study contain DNA that tells a story. The two Neanderthals from Western Europe were closely related to the last of the Neanderthals that lived in the same area 80,000 years later.

The early Neanderthals had more in common with the later Neanderthals than they did with their contemporaries who lived in Siberia at the same time.

The researchers believe that the early Neanderthals migrated to Siberia. That migration was followed by a later one from Europe that replaced the population there.

This provides European Neanderthals with a stable ancestry. The last Neanderthals who lived 40,000 years ago were all descended from a common ancestor.

The study published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

“The result is truly extraordinary and a stark contrast to the turbulent history of replacements, large-scale admixtures and extinctions that is seen in modern human history,” said a statement from Kay Prüfer, study supervisor and group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

The male Neanderthal in the new study also contained an intriguing secret in his mitochondrial genome, which differed from the nuclear genome. More than 70 mutations made him unique when compared to mitochondrial DNA from later Neanderthals.

The researchers believe that this means the early Neanderthals in Europe could have descended from an unknown population.

“This unknown population could represent an isolated Neandertal population yet to be discovered, or may be from a potentially larger population in Africa related to modern humans,” said a statement from Stéphane Peyrégne, study author and PhD student in evolutionary genetics at the Planck Institute.

A different study published in the journal PLOS ONE on Wednesday also found that Neanderthals repeatedly occupied an open-air settlement, rather than a cave, in Israel between 54,000 and 71,000 years ago.

The ‘Ein Qashish site in northern Israel contained Neanderthal bones and more than 12,000 artifacts including tools, animal bones and other resources.

This site was occupied just before Neanderthals vacated the area.

“[This is] raising questions about the reasons for their disappearance and about their interactions with contemporaneous modern humans,” said Ravid Ekshtain, study author and postdoctoral student at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.