When Ebola first struck this city of more than a 100,000 people last September, many here didn’t believe it was real.

As the disease latched onto families and spread through tightly packed neighborhoods, rumors began spreading of organ harvesting and political conspiracies, even as more people got sick and died.

When the ambulances came to take people away - they would never see them again.

“They didn’t know where they were taking them. They just thought they were going ‘over there’ to die,” says Sylvestre Zongwe, a Congolese manager of primary healthcare at French NGO The Alliance for International Medical Action (Alima).

So instead of going for treatment, many stayed at home and died, their bodies still highly contagious and deadly for the family members who buried them.

“Fear prevents good management of the epidemic. Fear makes it difficult to break the chain of transmission. What was needed was to break the fear,” says Zongwe.

It’s this extreme mistrust, along with simmering conflict and what many responders on the ground believe has been a flawed response, that has allowed the world’s second-biggest Ebola outbreak on record to continue unabated more than 10 months after the first cases were found.

Despite millions of dollars in funding, and an effective experimental vaccine, Ebola is spreading to new parts of Congo’s North Kivu and Ituri provinces and re-infecting areas thought rid of the virus. This month, it also made the long-feared jump across the border to neighboring Uganda, though at this stage those isolated cases appear to be contained.

A conflict the world forgets

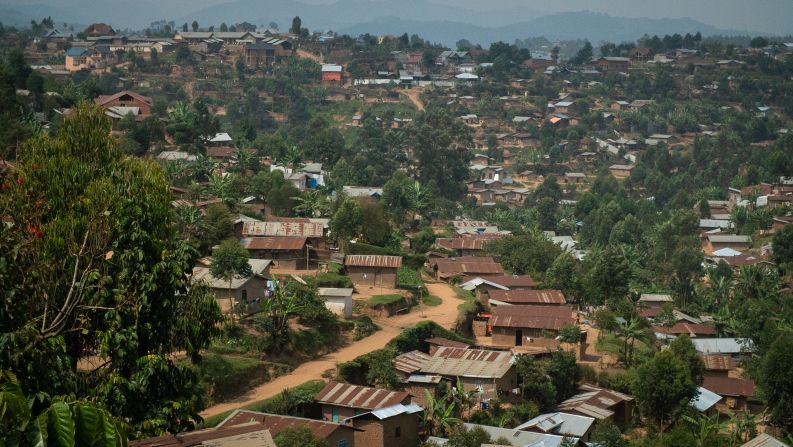

Butembo’s residents live at the frontier of a conflict that the world often forgets.

Hemmed in by multiple armed groups that commit repeated atrocities and harassed by the national military frequently accused of human rights abuses, they are famously and understandably distrustful of newcomers.

Earlier this year, unknown assailants destroyed Ebola treatment centers in Butembo. In April, a World Health Organization epidemiologist was killed in an attack on the University Hospital. In total there have been 130 attacks on health facilities between January and mid-May, causing four deaths and injuring 38.

Because of these security concerns, the White House barred world-renowned specialists of the US-based Centers for Disease Control from setting up a base in the heart of the epidemic (although it does have staff based in the regional capital Goma.) Similarly, Doctors Without Borders (Medecins Sans Frontieres) closed its treatment centers in some Ebola-hit areas and retreated to Goma.

Faced with an epidemic that is out of control and continued violence targeted at the response, health authorities are urgently searching for a different strategy to stop Ebola.

“During the first seven months of the epidemic we had more than 1,000 cases, now we have more than more than two thousand cases in a very short time,” says Antoine Gauge, a response specialist with Doctor’s Without Borders (MSF).

A draft internal World Bank assessment on the response from late May seen by CNN, describes the mounting shock at the rising death toll.

“Alarmed by the huge and unexpected surge in recent months in the number of new cases, a number of aid agencies and implementing partners have expressed concerns over many aspects of the response,” it reads.

Fighting Ebola in the Congo

It describes a response top heavy on operational costs like salaries and hazard pay. More than half of the budget for WHO’s strategic response plan during that period was allotted to staff remuneration. At the same time, it also shows that WHO was 40 million dollars short of its requested funding.

“We are absolutely outraged about how this response is going,” one senior humanitarian official based in North Kivu told CNN, saying that WHO would be better served by letting more nimble expert teams, that cost far less, do the work. The official refused to be named, citing fear of criticism from the WHO.

Christian Lindmeier, a spokesman for WHO, says the organization is committed to the people of the DRC affected by the disease and that every key aspect of the response was labor-intensive.

“As some partners and NGOs have had to leave due to insecurity or other reasons, WHO has stepped in and absorbed their tasks,” he said in an emailed statement.

“We owe a great deal of gratitude to the 700 brave WHO personnel who, working in partnership with the DRC Ministry of Health and hundreds of their national health workers, ensure that the response continues to operate across all vital functions, particularly when support is not immediately available from others.”

Community care

Alima, the French NGO, believes it has found a solution to the mistrust that has stopped people seeking treatment. It’s both hidden and in plain sight. Perched half-way up a hillside next to a school, their Ebola reception center is right inside a local clinic in the heart of the community.

A thermometer and a quick consult separates incoming suspected Ebola cases from other patients.

Community members were brought in and consulted at the beginning of the construction.

There are no alarming Ebola warning signs and posters. It just looks like part of the existing clinic. And that was the point: It’s not a scary place, hidden away. It’s in the community, as part of a system that treats all ailments.

“As soon as we fixed our approach, the results were there,” says Zongwe.

But to the frustration of Alima, it is the only reception center of its kind in Butembo. Plans to build more have stalled. And, while innovative, it isn’t nearly enough to stem the spread.

“This potentially could’ve been controlled earlier in the outbreak, when it was in a rural area, but letting it go fester underground with unknown chance of transmission, has really prolonged it, and we need to make sure we do everything we can to stamp it out now,” says Dr. Ben Dahl, a leader of the CDC response based in Goma.

Innovation in treatment means if Ebola victims are identified quickly and get to treatment centers from reception centers, hospitals, or clinics, they have a much better chance of surviving.

To make treatment easier and less intimidating, Alima has developed what they call “the cube.” Separated by a thin layer of transparent plastic, patients are able to interact more directly with doctors – they can talk to family members who visit. All of it is an attempt to reduce the fear of Ebola and convince people to come in.

Major reset

During and after the devastating Ebola outbreak that spanned several countries in West Africa from 2014 to 2016 and killed more than 11,000, the WHO faced scathing criticism for acting too slowly and warning the world too late.

In response, the global health agency reorganized its emergency response structure and strengthened its operations.

But in this outbreak, at least according to the responders we spoke with on the frontlines of treating Ebola, it hasn’t worked as planned.

David Gressly, freshly appointed by the UN as an Ebola Tsar of sorts, says the Ebola emergency response has gone through a major reset in recent weeks in the wake of internal criticism and a mounting death toll.

“If the virus continues to circulate, it remains a constant threat to spread to other provinces in this country and to neighboring countries and one day it will if we don’t find a way to bring it to a halt,” says Gressly, who previously managed the region’s UN peacekeeping operations.

CDC’s Dahl says that the existence of the vaccine, which while experimental has been found to be 97% effective in the Congo, has led to complacencyand the legwork of tracing patient contacts and quickly isolating them has not been done thoroughly.

“We were very fortunate to have this vaccine. It has probably reduced some of the cases and without it, we would have a much larger number of cases,” he says.

“But they have not been doing the public health fundamentals of quickly following all the contacts, listing all the contacts, and isolating them as soon as it becomes symptomatic,” he says.

He says around half of cases are still unknown to the contact listsand a large number of positive cases are deaths in the communities – from people who wouldn’t trust or couldn’t get to early treatment.

Contact lists allow epidemiologists to ring-fence an outbreak. When a positive case of Ebola is identified, the victim is interviewed to find out who they were in contact with. All of those people get on a list and, in an effective outbreak response, they are closely monitored.

To get this outbreak under control, the CDC says more than 70% of cases need to seek treatment early and upwards of 80% of cases need to be on the contact lists. Otherwise, it will continue to spread.

Beaten up and stoned for taking temperatures

Samuel Mutahwa was unemployed when the virus hit Butembo, but when the outbreak hit he volunteered to help. Now he plays a critical detective role of tracing contacts that could help break transmission.

Armed only with a thermometer, he leads his contact tracing teams through the neighborhoods of Butembo. Twice a day for 21 days – the maximum amount of time from time of infection to onset of symptoms – they follow up with their list of patient contacts.

Mutahwa entered the compound of a grandmother and grandson that visited a sick friend in hospital. The friend later died.

“36.8 – she is fine,” says Mutahwa, holding a thermometer up to the smiling woman.

But earning the trust of his own community has been a hard fought and dangerous process. In the early months, Mutahwa says that he was beaten up and stoned.

“They said they were going to kill me. But I said no, I know what I am doing. I have to save the life of my people,” he says.

Survivors part of the solution

Ebola is an intimate disease that is highly contagious but only contracted through direct contact.

It attacks families and then spreads through communities – often through so-called “super-spreaders” the 20% of cases that spread the disease to 80% of the people.

It is often the personal choices of Ebola victims that can have an outsized impact on the transmission chain.

When the sister of Roger Mumbere Wasukundi, 17, got sick earlier this year, he says nobody wanted to believe that she had Ebola. They didn’t even believe that Ebola existed.

After they buried his sister, his aunt got sick and quickly died. Roger, his mother, and his father all contracted the virus. Only Roger and his mother survived.

“I was sent to the treatment center because I didn’t want to give up. They told me I could survive and I believed them. Everyone prayed for me,” he says, sitting in his classroom in Butembo.

He still dreams of being a lawyer, but the virus still affects his health, his eyes clouded by the after effects of Ebola.

He believes that survivors like him can help turn the tide in the fight against Ebola and dispel the mistrust that has made the disease so hard to beat.

“Ebola survivors (need to) go talk to communities. Because this epidemic is very real,” he says.