As President Donald Trump continues to make clear that he wants to kill the Affordable Care Act, new research suggests that a big part of the ACA – the expansion of the Medicaid program – was linked with fewer cardiovascular-related deaths in counties where expansion took place.

Between 2010 and 2016, counties in states where Medicaid expanded had 4 fewer deaths per 100,000 residents each year from cardiovascular causes after expansion, compared with counties in non-expansion states, according to the research. The findings were presented at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions on Friday. Enrollments for insurance under the ACA began in 2014.

“The overall results of this study are that after expansion of Medicaid in 2014, the areas in the country that did expand had a significantly lower mortality rate compared to if they had followed the same trajectory as the areas in the country that didn’t expand,” said Dr. Sameed Khatana, a fellow in cardiovascular disease at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, who was first author of the new research.

“It’s important to study health policy in a more quantitative manner, and I think we’re seeing an increasing number of research studies on these kinds of topics,” he said. “This research just sort of fits in with a growing trend of research in this area.”

Anyone can qualify for Medicaid based on income, household size, disability, family status and other factors, but the ACA allows states to expand Medicaid eligibility so that residents can qualify based solely on whether their household income level is a certain percentage below the federal poverty level.

The new research is preliminary and still in its early stages, but it comes as the Trump administration appears to be doubling down on trying to overturn Obamacare.

In a surprise move last week, the Department of Justice said it agreed with the December ruling of a federal judge in Texas that invalidated the health reform law. The case is now in federal appeals court.

Eliminating Obamacare could leave roughly 20 million more people without health insurance, according to a recent report from the Urban Institute, an economic and social policy think tank. The President said this week that he will not push for a replacement plan until after the 2020 election.

The new research included mortality data on adults ages 45 to 64, from 2010 to 2016, in all states except Massachusetts and Wisconsin. In those two states, there was Medicaid expansion that was not related to the ACA.

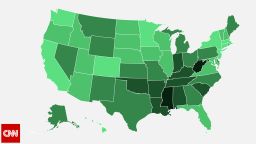

As of 2016, after excluding Massachusetts and Wisconsin, 29 states and the District of Columbia expanded Medicaid eligibility, but 19 states had not, according to the data that came from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s WONDER database.

The researchers took a close look at state-by-state differences when it came to cardiovascular-related deaths on the county level, before and after Medicaid expansion.

They adjusted those differences to account for factors that might skew the findings, such as unemployment rates, median household incomes and the number of cardiologists per 100,000 residents.

The researchers found that, compared with counties in non-expansion states, counties in expansion states had a greater increase in health-insurance coverage for low-income residents and a significantly smaller increase in cardiovascular mortality rates.

Between 2010 and 2016, cardiovascular-related deaths rose from 141.9 to 142 per 100,000 residents each year in the counties in expansion states, while cardiovascular-related deaths rose from 176.1 to 180.6 per 100,000 residents annually in the counties in non-expansion states, the data showed.

The research had some limitations. Because it was observational, the researchers were unable to completely tease out any contributing factors that could have influenced the differences between counties in expansion and non-expansion states.

“Medicaid expansion was the major health policy that occurred in 2014, but there were some other things as well that weren’t captured by our study, or that were happening around the same time, that could potentially explain some of these findings,” Khatana said.

“Another [limitation] is that we looked at cardiovascular diseases as a whole, so we sort of lumped everything together: heart attack, stroke, arrhythmias, et cetera. Because any one cause of death causes very few deaths in individual counties, which was our level of analysis, we’re not able to say which specific disease is responsible for these changes,” he said.

Public health experts have long known that the presence or absence of health insurance can influence death rates, said Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, who was not involved in the new research.

“This study is absolutely in keeping with that,” Benjamin said, but he added that a closer look at the research is needed to confirm that the correlation between reduced cardiovascular deaths and Medicaid expansion is truly driven by the ACA and not other factors.

Yet “if you think about the fact that cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death, followed by cancer, it would not be surprising that the leading cause of death goes down when you give people health insurance,” he said. “We know very clearly that again, even in the Medicaid program, that if you give people coverage, mortality goes down.”

The new research “contributes to the limited knowledge on how Medicaid expansion affects health outcomes,” said Dr. Olena Mazurenko, an assistant professor in the Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health at the Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis campus, who was not involved in the research.

Mazurenko was first author of a paper published last year in the journal Health Affairs that found expansion to be associated with increases in coverage, service use, quality of care and Medicaid spending.

That finding was based on a review of 77 previously published studies on Medicaid, but only 16 examined quality of care and health outcomes.

“The Medicaid expansion occurred only a few years prior; it was too early for studies to reliably determine the effect of Medicaid expansion on clinical measures of health status and, certainly, too early to determine the impact on any long-term outcomes,” Mazurenko said.

“Importantly, none of the limited number of published studies reported poorer outcomes as a result of Medicaid expansion,” she said. “With more time, researchers will have the opportunity to determine the effects of Medicaid expansion on population health more comprehensively.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Dr. Ivor Benjamin, president of the American Heart Association, called the new research “exciting” and said the association has gone on the record with its support of “affordable, accessible and available” health care.

“So that is our position. The next question then is, how much does it cost?” he said. “What’s the value that we will get from having people be able to have affordable insurance? What’s the value? And what this data help to provide in that conversation is that, ‘Yes it matters.’ “

CNN’s Tami Luhby contributed to this report.