As director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, Anthony Leiserowitz gets brought in to a lot of conversations about the topic. He shapes stories about it with other scientist for publication. He talks to CEOs and politicians. He gives lectures. He’s ready to answer just about any heavy questions about the complicated subject. But often, the first question he gets is a simple one.

Is it global warming or climate change?

“If I had a penny for every time I was asked that,” Leiserowitz mused.

The term “global warming” seemed to be more in vogue in the past decade, although President Trump uses it these days to make fun of the concept on Twitter.

In politics, in public policy and in everyday conversation, for the most part, “climate change” has become more common. The United Nations has the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The National Climate Assessment says it summarizes the impacts of “climate change.” Congress named its subcommittee Environment & Climate Change, not Global Warming.

Check Google trends, though, and the terms seem to be typed into a browser at about the same rate.

So, which is it?

The experts will tell you it’s not an either/or answer but more of a “yes, and” kind of response.

And the reason why there are different terms to describe one phenomenon is a tale that reveals how thinking can change on a topic – and how language was shaped by politics and talking points in a secret memo.

Glass of a hothouse

The first terms used to describe the impact that burning fossil fuel had on the Earth’s climate were fit for a garden.

As early as the 1800s, scientists suspected that industrialization changed the planet’s temperature. Like Trump, the scientists didn’t always think that was bad.

“Well, Arrhenius lived in Sweden. You can’t blame him,” Jim Fleming said of Nobel Prize winner Svante Arrhenius, the first scientist to calculate the impact that carbon dioxide in the atmosphere had on temperature.

Fleming, a professor of science, technology and society at Colby College who has written about the history of climate science, nicknamed Arrhenius “the Cold Swede.”

The purpose of Arrhenius’ 1896 paper was to understand the cause of the Ice Age, but later, he linked coal production to greater concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Arrhenius would call this phenomenon “drivbänk”; the Swedish translates to “hotbed” or “hothouse.” His colleague, meteorologist Nils Ekholm, used the term “greenhouse,” Fleming said.

Until about the 1970s, scientists had a strong sense that human activity was changing the climate, but they debated whether the planet would get warmer or colder. Often, they would use the term “inadvertent climate modification” or, scientists say, just stick with the “greenhouse effect.”

Global warming: A beginning

“Global warming” started getting picked up in the scientific literature in the 1970s, after Wallace Broecker popularized the term with his 1975 paper, “Climatic Change: Are We on the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming?”

The Columbia University professor, whom many called the “Grandfather of Climate Science” in obituaries in February, urged lawmakers to fund a national effort to understand it better.

In 1979, the first decisive National Academy of Science study looking at the impact of CO2 on climate, known as the Charney Report for its chairman, used Broecker’s term “global warming” to discuss the link between the increase in carbon dioxide emissions and surface temperature. It used “climate change” to talk about the other changes it would bring.

The media and some scientists sometimes used the term “global change,” but really started picking up on the term “global warming” much more often after covering James Hansen’s testimony at a Senate hearing in 1988 research shows.

“Global warming has reached a level such that we can ascribe with a high degree of confidence a cause and effect relationship between the greenhouse effect and observed warming,” the NASA scientist famously told the Senate.

Lynda Walsh, a professor in the English Department at the University of Nevada, Reno, who specializes in the rhetoric of science, noted that “the political stakes got higher in the early 1990s.”

That’s when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports raise alarms about it. Congress held hearings about global warming. Polls showed growing public concern.

Yet the term had its limits.

It’s complicated

“The term ‘global warming’ confuses people because it triggers thoughts about warmth, and it sort of lends itself to misinterpretation when it also impacts the cold,” said Mike Hulme, a professor of human geography at the University of Cambridge whose work focuses on the way climate change is discussed in public and political conversations.

Apparently, the Cold Swede isn’t the only one who wouldn’t mind warmer winters.

When Hulme started in the profession in the 1980s, scientists were using the term “greenhouse effect.” “Climactic change” or “climate change” became more popular in the 2000s.

“I think, on one level, climate change is a more accurate description of what is happening to the world weather systems and is a more neutral phrase,” Hulme said. “Climate change alters the weather system in ways that aren’t limited to temperatures.”

Climate change doesn’t just raise temperatures. It can make winters colder and storms more intense. It heats the ocean; it leads to flooding and more wildfires. It kills animals, plants, humans and much more.

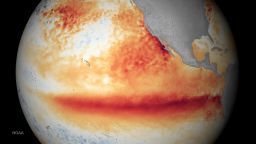

Top 5 years of measured ocean heat content

“You could think of global warming as the large macroperspective phenomenon,” said Naomi Oreskes, a professor of the history of science and an affiliated professor of Earth and planetary sciences at Harvard University who focuses on climate change. “Climate is more complicated.

“The term ‘global warming’ also doesn’t get at how it impacts weather locally and regionally.”

In scientific papers, “climate change” is the term used more frequently, studies show, although scientists will use “global warming” when specifically referring to the increase in the Earth’s actual surface temperature. In lectures, many scientists say, they use both.

“Keep in mind, scientists are trained to talk to each other, but if there are issues like this or like about vaccine safety, we need to think more about how we choose our words and be smart about our language,” Oreskes said.

Scientists did not workshop the term with focus groups or hire an ad agency to determine what words to use, rhetorician Walsh said. But there certainly were people who hired focus groups, and they had a very clear, non-scientific aim in mind: They wanted to downplay it.

The secret memo

Before he was president, Trump tweeted more than once that “hoaxsters changed name to CLIMATE CHANGE!” But it was Republicans, not Democrats, who initially pushed for the name change.

In 2002, GOP strategist Frank Luntz sent a memo to Republican candidates to create an environmental strategy. He argued that the environment is “probably the single issue on which Republicans in general – and President George W. Bush in particular – are most vulnerable.”

The memo suggests that candidates express their “sincerity and concern” about the environment, but he also wanted them to downplay concerns.

Using focus groups, Luntz discovered that ” ‘climate change’ sounds less frightening than ‘global warming,’ ” the memo explained.

“While global warming has catastrophic connotations attached to it, climate change suggests a more controllable and less emotional challenge.”

Luntz did not respond to a request for an interview.

A New York Times analysis at the time found that President Bush used the term “global warming” several times in his environmental speeches prior to the memo. Afterward, Bush shifted to “climate change.”

But people didn’t all switch because of politics. The National Academies explained in its 2005 report that the phrase “climate change” helps convey that there are changes in addition to temperature.

A 2014 report found that conservatives often used the term “global warming” more frequently, and liberal think tanks used “climate change.”

“Words are not buttons you can press to make them mean only one thing. That’s not the way it works in rhetoric,” Walsh said. “You have to consider the time and place and the words used and who is using them.”

So, which is it?

When people ask Yale’s Leiserowitz whether it’s climate change or global warming, he tells them he uses both.

“The key thing about terms like this is, they are plastic. Or, well, maybe since we are talking about the environment, we should say words are renewable organic latex or something,” Leiserowitz joked. “Essentially, meaning changes.”

Hulme and Oreskes said that some colleagues, to emphasize exactly how dire the situation is, will add a word to the phrase “climate change,” like “anthropogenic” or “human.”

“Sure, the climate will always change, but to communicate why it is bad, I sometimes will put a qualifier word with it and will say ‘man-made climate change’ or ‘disruptive climate change,’ ” Oreskes said.

Sam White, a historian who studies the role of climate in history, will also call it “man-made climate change” because “there are natural variations in climate as well as man-made climate change which is having a much greater impact,” White said.

Hulme said he has heard scholars try to come up with new terms, calling it “climate chaos,” “catastrophic climate change” or “weather weirding.”

“You have various forms of linguistic entrepreneurship to draw attention to this in slightly more melodramatic ways, feeling that ‘climate change’ is too neutral,” Hulme said.

Most scientists, at least in the scientific literature, would balk at the idea of putting “loaded and charged” terms with the phenomenon, said Erik Johnson of the Department of Sociology at Washington State University.

“Scientists are supposed to be neutral, and other people will do the politics,” Johnson said. “I’m just not sure scientists are capable of getting in the room together to figure out how we frame one message.”

Top 5 years of measured ocean heat content

Hulme said that if people wanted to be really specific, “ocean heating” may be a more accurate term, because 98% of the extra energy generated by human activity goes into the sea, causing serious problems. “But that’s still quite esoteric, and I don’t see that catching on anytime soon,” Hulme said.

No matter what terms people use to describe it, scientists and many policy-makers want you to call it something, because it’s important to keep talking about it.

“Words can pop loose from their meanings and moorings,” Walsh said. What’s most important is that the world continue to talk about what may be one of the biggest threats to this planet.