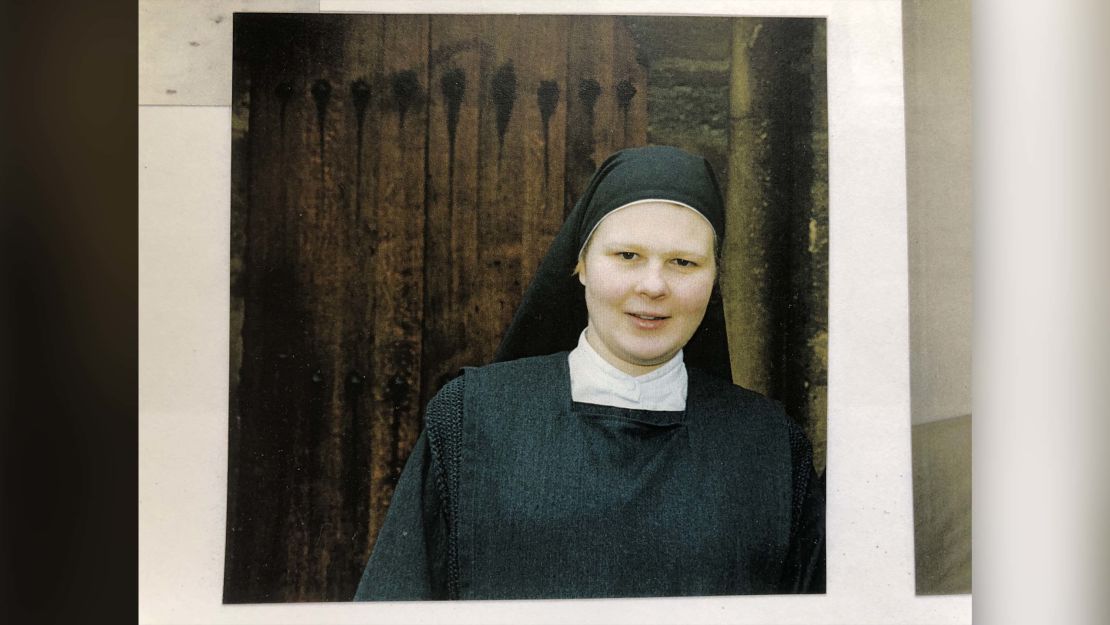

Lucie was just 16 when she became involved with a Catholic religious community after attending a holiday camp in Switzerland. At the time, she told CNN, she was “very, very, very alone” and looking for friends and affection.

What she found at first was “really like a family,” she said. But two years later – by which time she was preparing to become an “oblate,” a lay person affiliated with a religious order – she says a pattern of sexual abuse by a charismatic priest who she considered her spiritual father began.

It took 15 years for Lucie – a pseudonym used at her request to protect her family – to realize that what she says she experienced over several months in the 1990s was abuse. At the time, just 18 years old, she felt “disgusted” by the physical intimacy she says the priest forced on her but also wracked by guilt and powerless to stop him.

“It was like automatic you know. He wanted to go to the end – to ejaculation – and I was just like an object for him and I had a feeling he did this a lot of times,” she said.

Her story is not unique.

CNN has spoken to several other women who say they are victims of the devastating sexual, psychological and spiritual abuse they suffered within the Community of St. John.

For Liene Moreau, who says she was abused by a priest in France for 15 years, starting when she was a novice, or trainee nun, in her 20s, the breach of trust and of faith were the hardest part to deal with.

“The psychological abuse was worse than the sexual abuse; it’s my inner life, he took my dignity, my femininity, all that I was. And still today it is very hard to have confidence in myself,” she said.

‘Acts contrary to chastity’

The order to which the women belonged, the Contemplative Sisters of St. John, was founded at St. Jodard in the Loire region of France, in the early 1980s – one of three orders set up by Father Marie-Dominique Philippe.

Laurence Poujade, a former nun who now heads a victims’ organization, says Philippe’s doctrine – and his crimes – are at the heart of the order’s problems today.

“He believed that because he was involved in mysticism, everything was possible,” she told CNN. “But no, everything was not possible.

“I think very often about the victims who will never be able to be heard,” she said. “We are talking about victims who don’t speak out, but what about those who went straight to psychiatric hospitals, what about those who mutilated themselves? I know of one case, her parents called me to tell she had cut out her own tongue. What can you say? What can have happened for a victim to do that?”

In 2013, seven years after his death, the Brothers of St. John revealed that Philippe “had committed acts contrary to chastity with several adult women whom he accompanied at the time.” Nuns were among the victims of this abuse, the order later confirmed. For years, there were also rumors about other priests and other victims within the order.

But the lid was fully lifted on the scandal earlier this month, when Pope Francis for the first time acknowledged the sexual abuse of nuns and other women by priests and bishops as a “problem” for the church.

In one breakaway part of the Community of St. John, “corruption” had reached the point of “sexual slavery,” he told reporters, leading his predecessor, Pope Benedict XVI, to dissolve it in 2013.

The Vatican subsequently sought to soften that characterization, saying that when Francis “spoke of ‘sexual slavery,’ he meant ‘manipulation,’ a form of abuse of power which is reflected also in sexual abuse.”

But the genie was out of the bottle. And it’s clear the Catholic Church – already grappling with a global scandal over the sexual abuse of children by clergy – has questions to answer.

Pope’s words ‘like a bomb’

Shortly after the Pope’s comments, the Community of St. John issued a statement recognizing that, beyond the allegations against its founder, “some sisters or former sisters have also testified that brothers and priests of the community were also responsible for abuse. Many of these brothers and priests have already been sanctioned and others are in the process of being sanctioned.”

CNN contacted the Vatican for a response to this story; its spokesman would not comment on any specific allegations but did confirm that cases involving clerics belonging to the Congregation of St. John were being investigated by the Vatican.

For Lucie, Francis’ words were a watershed moment. They brought huge relief – and a sense of justification after years spent struggling to be heard. “When I first read the article, it was incredible, it was like a bomb,” she told CNN, in her first interview about her experience with a branch of the St. John community in Switzerland.

“I thought, like, okay, everything we tried to tell the Vatican, the Pope, the bishop, there is something happening… because sexual abuse, nobody ever say before.”

‘I couldn’t see him as a predator’

Lucie told CNN her alleged abuser had misused his position of authority and the order’s central tenet of “loving friendship” to justify what he was doing.

On the first occasion Lucie says the priest tried to kiss her on the mouth, she pushed him away. But she says he was not deterred. “I didn’t feel I had any power in front of him, I couldn’t say really something. When I was trying, he always had arguments to tell me that I’m wrong and he’s right. How can I not believe him?” she told CNN.

“He was taking off his clothes and I saw everything – it was the first time of my life, and I was really disgusted. But I realize that on the moment I didn’t feel anything. Because I was not there anymore, it was a protection, to not feel.”

Lucie has struggled to grasp why she didn’t realize what was happening at the time but now believes it was down to that disassociation and what she calls brainwashing. “It was absolutely 100% impossible for me to see him like a predator,” she said.

In response to the allegations made by Lucie, a spokesman for the St. John community told CNN there had been “several accusations of sexual abuse” made towards this particular priest and that he had left the community 10 years ago.

“It is now the Vatican’s responsibility to look into these complaints and a legal proceeding is ongoing,” the spokesman said. “All the measures at our disposal have been taken to remove him from the community.”

Search for justice

The problem is not isolated to one rogue community. In recent months, CNN and several other news organizations have highlighted the abuse of nuns by male clergy elsewhere in Europe, as well as in Asia, South America and Africa.

Bishops from around the world have been summoned by the Pope to an unprecedented summit this week in Rome to discuss the crisis over clerical sexual abuse. But the four-day meeting will likely focus on the shocking array of claims of abuse of children.

All the women who spoke to CNN said their first struggle was simply to recognize the abuse for what it was. Only after many years did they seek justice, first within the church and then through the courts.

Lucie, who is now married with five children, tried to take her alleged abuser to civil court, but a Swiss public prosecutor ruled that the statute of limitations had expired. A lawyer for the priest declined to comment to CNN on the allegations made by Lucie.

Lucie, who eventually moved to Belgium and still attends church regularly in the small village where she lives, says that before attempting legal action, she had tried unsuccessfully to raise the issue with the St. John community.

“After I don’t know, maybe two years, I was conscious that the community was not doing anything, I was talking about (it) with other victims, realizing that they know, that it’s been 15 years that they know, that there’s other victims. So they don’t want to do anything,” she said.

Moreau, now 41 and married with three daughters, tried to take her alleged abuser to court in France, but the statute of limitations meant the case was dropped by the Tours prosecutor.

She sought a meeting in 2017 with the priest in question, to confront him, but was advised against it by the order. A brother from the St. John community sent an email in November 2017, seen by CNN, in which he acknowledged “the gravity of the abuse” Moreau suffered but said she must see a psychotherapist for her own sake before seeking contact with that priest.

In letters shown by Moreau to CNN, dating from her time with the order, the priest suggests “discretion… in the future we will have to meet elsewhere … I pray that we can find clever ways of meeting.” He ends by saying that his “crazy love” for her comes from Jesus.

Moreau, who is Lithuanian and at first spoke limited French, now thinks the priest may have targeted her in part because of that.

“I was far from my family, in a foreign country, this is already something, and that might also be why he chose me, an easy prey in the end,” she said. The priest also made her believe that the fault was hers, as a “temptress,” she said, despite the fact she says she tried to distance herself from him.

The priest in question is being investigated by the Vatican and has been removed from some of his duties, a St. John community spokesman said.

In a February 7 statement, the leaders of the three orders within the Community of St. John said they condemned “every situation of sexual abuse and abuse of power” and reaffirmed “their clear resolve to eradicate any and all abusive situations.”

They said the order dissolved by Benedict in 2013 – and referenced by Francis – was a small, Spain-based splinter group which separated from the St. John community in 2012 after church authorities tried to bring in reforms following Philippe’s death.

The dissolution of the order has brought little closure for Moreau, who is still coming to terms with what she says happened to her.

“It lasted for 15 years, and it’s now been two years since I was able to put the word ‘abuse’ on this, and still today it’s very complicated to admit that I might be a victim,” she said.

“If only just for myself, I don’t want to be a victim. And yeah, I feel responsible because he made me responsible, he made me complicit in his acts.”

CNN’s Melissa Bell and Saskya Vandoorne reported from St. Jodard, while Laura Smith-Spark wrote from London. Barbara Wojazer contributed to this report.