If there’s a serious recession on the horizon, the world’s central banks may have trouble fighting it.

Central banks took dramatic and unorthodox steps to prevent economic collapse during the financial crisis. They slashed interest rates, andin the years that followed spent trillions on bonds as part of an effort to spur growth.

One decade later, global central banks are only starting to reverse those moves.

Interest rates in developed economies remain incredibly low; in some places, they’re even negative. The Federal Reserve is unloading some of the bonds it bought, but central banks in Europe and Japan have not yet done so.

The question now is whether central banks waited too long to raise rates to more normal levels, leaving them unprepared for the next crisis.

“If we have a recession, I think it’s going to be worse than normal,” said Kenneth Rogoff, a professor at Harvard University and former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund. “It will be more difficult to respond.”

Politics is also making lifemore complicated for central banks. In countries like India and Turkey, they’ve faced threats of political interference, while President Donald Trump has repeatedly criticized the Federal Reserve.

‘Another blown tire’

The outlook for the global economy has dimmed significantly in recent months as trade tensions caused growth to slow in countriesincluding China and Germany.

The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have cut their growth forecasts for 2019, and experts warn of more pain from US interest rate hikes, trade conflicts and geopolitical risks such as Brexit.

No one expectedsynchronizedglobal growth to continue forever. But actions taken by central banks over the past 10 years could limit their response to a sharp slowdown now.

“Think of a car traveling on a bumpy road with no spare tires. You really don’t want to have another blown tire,” said Mohamed El-Erian, the chief economic adviser at Allianz (AZSEY).

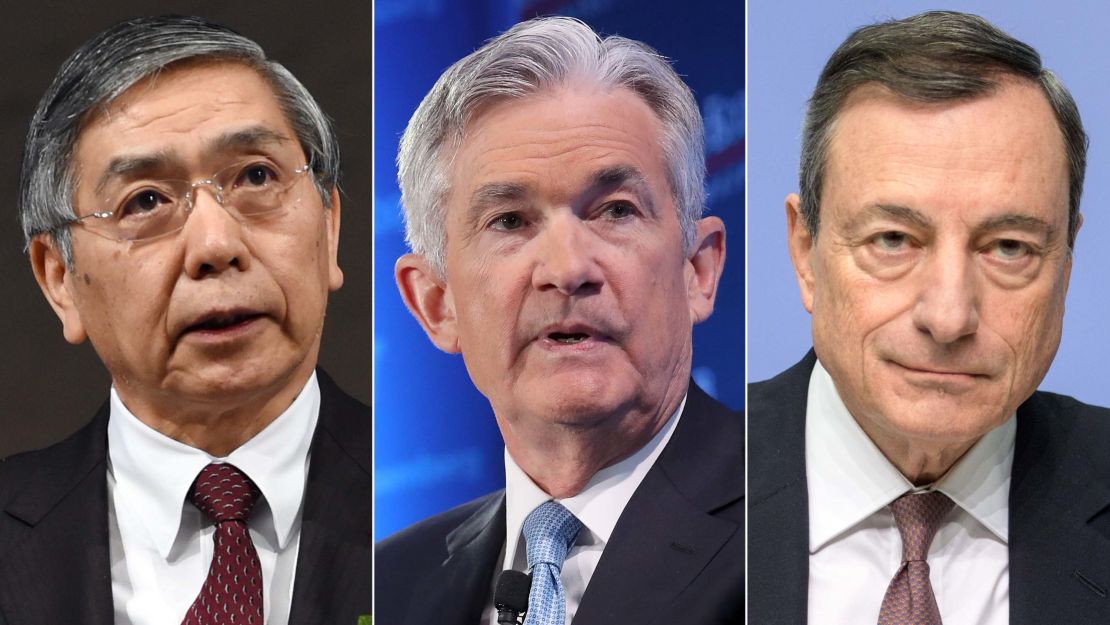

El-Erian said the Federal Reserve, which raised interest rates four times in 2018, is in better shape than other leading central banks. But its benchmark rate — currently set between 2.25% and 2.5% — remains historically low, limiting the room it has to cut in order to spur growth. “Even the Fed has less flexibility than in the past,” he said.

The European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan are worse off. The ECB’s key lending rate is 0%, while its deposit rate is -0.4%. In Japan, short-term rates have been in negative territory since 2016.

“They’re very limited in what they can do,” Rogoff said.

Running out of ammo

Then there’s the unprecedented moves by central banks to snap up trillions of dollars worth of bonds after the crisis to support growth, a policy known as quantitative easing, or QE.

The United States only started shrinking its $4.5 trillion balance sheet in October 2017, and still holds roughly $4 trillion in debt securities.

While the Federal Reserve could technically start QE back up again, El-Erian said such a program would “likely be less effective in promoting sustainable growth.”

Europe only ended itsQE program in December after creating €2.6 trillion ($3 trillion) in new money. Total holdings at the Bank of Japan have reached 554 trillion yen ($5.1 trillion) last year as it remained in stimulus mode under Governor Haruhiko Kuroda. Those assets are worth more than the country’s entire annual economic output.

Put simply, the central banking system is “running out of ammo,” according to Ed Yardeni, president of investment advisory firm Yardeni Research.

“They may not have as much firepower or credibility next go-round,” he said.

Messy politics

On top of these tough conditions are political pressures that could complicate the ability of some central banks to mitigate or respond to a slowdown.

In December, the governor of the Reserve Bank of India abruptly quit after Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government leaned on him to do more to boost the economy ahead of elections.

The rapid appointment of a former government official to take his place further stoked fears of political meddling.

Earlier last year, Turkey found itself in crisis after its central bank refused to raise interest rates despite soaring inflation, which is turn sent the lira plummeting.

The decision came after President Recep Tayyip Erdogan indicated that he wanted to take control of setting interest rates, which he described as the “mother and father of all evil.”

In the United States, Trump has taken to publicly chastising Fed Chair Jerome Powell over rate hikes. Trump has even polled advisers on whether he has the legal authority to fire Powell.

“There [are] more and more examples of how central banks’ independence is something that’s not flying, particularly in places where you have populist leaders,” Yardeni said.

Questions over political independence of central banks, combined with their relative lack of horsepower, means they might not be able to come to the rescue in a recession.

“There may very well be limits to what monetary policy can accomplish,” Yardeni said. “And it may be a mistake to tell the public they can fix all of our problems.”